At the risk of sounding like a cross between a Monty Python Yorkshireman and one of the dreary boomers still banging on about bloody Woodstock, kids today just don’t understand what it was like being an indie music fan in the ’80s. Back then, for one, ‘independent’ music really meant something (yeah, yeah, grandpa), and the gap between ‘indie’ and mainstream was near-absolute. Even such icons today as Nick Cave were resolutely shut out from airplay.

If you were a music fan interested in anything other than Michael Jackson or Madonna, you were mostly shit out of luck unless you could pick up an inner-city public radio station from Melbourne or Sydney. There were two bands, though, who were just too good for the mainstream to ignore for long and who kept us indie fans sane: REM and the Smiths.

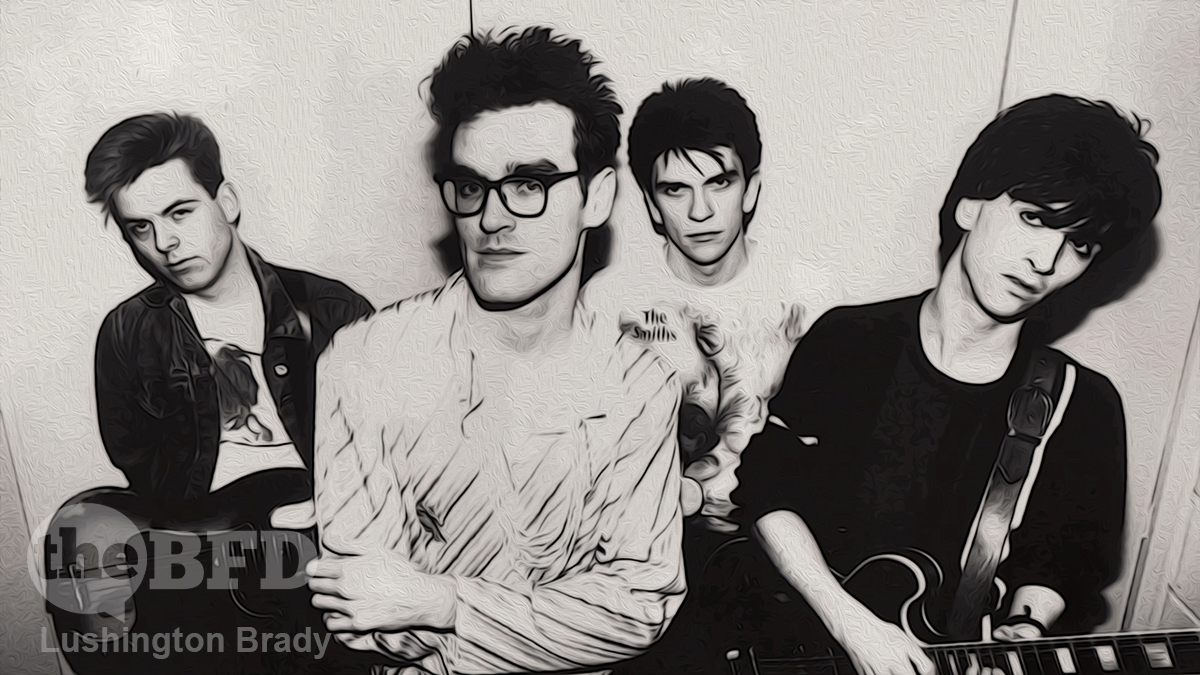

It’s been 40 years since the Smith’s debut single. In recent weeks, bassist Andy Rourke passed away. Naturally, the right-on critics have been working themselves into a lather – and almost completely missing the point. The Smiths’ greatness was most certainly not in the two accolades usually conferred on great bands (and especially on the Smiths): musical uniqueness and influence.

‘Over the past 40 years, you can see their aesthetic and spiritual influence in everyone from the Stone Roses to Oasis and the 1975,’ they tell us. If only! Those bands are derivative, certainly, but of the Smiths? Guitars and the North of England aside, it’s hard to imagine greater artistic gulfs. The comparison between the emotional open wound of the Smiths’ output with the 1975’s immaculately hollow, precision-tooled-for-Spotify tunes is laughably wide of the target. I strongly suspect you could remove the Smiths from history, and those bands – and pop music in general – would sound exactly the same.

There is also another repetition of the assertion – first made by John Peel and oddly never challenged – that the Smiths sounded like nothing else when they first appeared, and that everyone was knocked over by their originality.

To make such an assertion, though, you’d have to ignore everyone from Echo and the Bunnymen to the Lotus Eaters.

So, what did make them special?

Two things: their celebration of ordinariness, as exemplified by their very name, and Morrissey.

The band bucked the trend of the day-glo multicoloured world of the ’80s: all synthesisers and videos of Bowiefied men disappearing in slow motion or pouting with their cheeks sucked in. The Smiths released albums and singles with sleeves of forgotten ’60s actors, their photographs washed in dun, plum, taupe and umber. People have forgotten how funny that was.

Most pop music takes place in some unfathomably remote dream world of aspiration, or a drugged withdrawal from reality. But, as their name suggested, the Smiths were bread and butter, more Ena Sharples than Brian Eno.

Look at the chasm in January 1984 between Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s “Relax” at number one in the charts and “What Difference Does It Make” by the Smiths at number 12. The first is a pounding multi-platform extravaganza of acrobatic homoeroticism; the latter, the story of a thwarted confession of… something, conveyed in the language of the everyday. The lyrics took in school, jobs, money troubles, fumbles and messy approaches; the actual warp and weft of teenage life.

Which is why, despite the critics’ latter-day supposed epiphanies of the Smiths’ greatness, at the time most people hated them. As Robert Forster of the Go-Betweens has said to swooning modern critics, “If we were so fucking great, how come nobody bought our records?” Similarly, the Smiths barely scraped anywhere near the top 10 of the charts, although their albums did better (Meat is Murder making No 1).

And if most people hated the Smiths back in the day, even the critics today hate Morrissey.

Which is odd, because, without Morrissey, the Smiths would have sounded like Haircut 100. While Morrissey might be a terrible novelist (but, then, so’s Nick Cave), his finesse with words in the medium of pop song has rarely been equalled. No wonder dudebro contemporary Henry Rollins always hated him.

Morrissey remains almost unique as an artist in the pop world, as his only means to communicate clearly and sincerely is in the poetic, lyrical mode. Everyone else seems to have forgotten that’s what we have the poetic, lyrical mode for.

More importantly, like Cave, Morrissey has steadfastly refused to conform to the expected opinions of the rock-star class. But, whereas Cave just quietly does his own thing and politely dismisses attacks, Morrissey was and is in-your-face about being Morrissey.

The disregard of the musical cognoscenti for Morrissey’s post-Smiths career has obvious motivations […] Morrissey has made some of his best records much later on in his life, but they go unheralded – even, now, unreleased.

Which brings us to another of the caveats, what the Guardian calls ‘the singer’s current views’. Morrissey’s trenchant opinions during the lifetime of the Smiths (wishing death on Mrs Thatcher, supporting animal rights terrorists, etc) didn’t bother the music press, when these could be categorised as left wing.

But when Morrissey kept right on saying what he always had – that there is an essential, inborn uniqueness to being English; worse, that the contemporary dogmas of multiculturalism are just so much bullshit – the critics clutch their pearls. When Morrissey stuck to his animal rights guns and criticised the barbaric treatment of animals in China, the critics fainted in droves.

For forty years, he has seemed like an interloper in the milieu of indie – the priggish students, the turgid music press and the Guardian. Of course, these people always get it so wrong. The Smiths were always too big, too exceptional, for that narrow little world.

Spectator Australia

Still, I’ve never forgiven the Smiths for breaking up before ever touring Australia. Or Morrissey, for abruptly cancelling his one Australian tour, literally as we were in the car driving to the Melbourne show.