OPINION

Caleb Anderson

First published on NZCPR

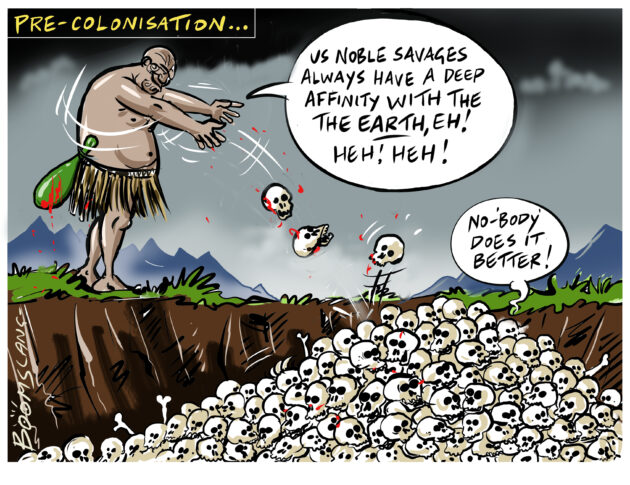

In the eighteenth century, the idea took root among the thoughtful classes of the “noble savage”. Genevan Philosopher Jean-Jacque Rousseau was prominent in painting a picture of indigenous societies as inherently peaceful and equal.

Many of the eighteenth-century European explorers set sail with these ideas in mind, often to have these dashed in their first encounters, some of these with New Zealand Maori.

Twenty-five crew were killed in Du Fresne’s encounter with Maori in 1772, Cook would never forget the deadly attack on his crew in 1773, the burning of the Boyd and murder (and cannibalism) of its crew in 1809, and all too obvious evidence of intense intertribal warfare, and endemic cannibalism, seemed to put the seal on the idea of the “gentle utopian savage”.

No doubt unnumbered Rousseauians returned to Europe no longer Rousseauians, and some did not return at all.

Rousseau’s idea that people in their natural state are fundamentally good, and that it is society that corrupts them, is highly problematic.

If history shows anything, it shows a broadly similar propensity to do evil things across time and culture, the primary limiting, or exacerbating, factor being the technological advantages one group might have over another.

As far back as any records go, and as amply evidenced in a vast array of anthropological artifacts, and ancient myths, we know, without any doubt, that competition between groups for resources, and the struggle to survive, has consistently revealed the darker side of man.

The perceptions of pre-European New Zealand as ordered, peaceful, prosperous, and equal is one of the great mischiefs of our age.

It defies undeniable evidence (anthropological and early written accounts) of endemic warfare, cannibalism, genocide, and lives that were brutal and short.

Even the notion of considered custodianship of the environment reflected necessity, more than some inherent and magnanimous oneness with nature.

In reality, human beings are neither fundamentally good, nor fundamentally bad, they are a mix of both. This includes the first settlers to this country, and every subsequent wave of settlers.

We are far more similar than we are different, are capable of good or bad in equal measure, and all have bloody ancestral histories if we go back far enough. To say anything else is mischief, but mischief is what we are very good at.

Psychoanalyst Alfred Adler (second in line after Freud) remarked often on our abilities to lie to ourselves. In fact, he said that we are perpetual liars.

We populate our worldview with facts that suit, we reject the facts that don’t, we paper over our faults (and our histories) and damn those of others (and their histories).

We love to project our darker side onto others, after all, we have to do something with it.

The tribalism of today is no different than the tribalism of old. The concept of Maori wonderfulness is as eminently nonsensical as that of European wonderfulness. It is just not as simple as this.

Once we accept this basic fact, and only once we accept this fact, will New Zealanders mend the mess that has been created by those who have made an industry of division.

Psychoanalyst Carl Jung (arguably next in line to Adler) said that life is a process of integration of our darker side. The more we can integrate, the more accepting we become of ourselves and others, and the better we are able to live with our individual and collective pasts.

I think there is such a thing as collective (national) integration.

Our willingness to address our history post-1840, while ignoring our history pre-1840, will create distorted perceptions and disastrous and unjust outcomes.

Open and honest discussions need to occur, free of propaganda and censorship.