OAP

Accuracy in Target Shooting

On the face of it, it is simple. The right size bullet has to leave the barrel at the right speed and twist to stabilise it to reach the target without becoming subsonic (under 1100 feet per second), as the bullet loses stability when it passes through the sound barrier. This is why subsonic .22 ammo is preferable for target shooting.

So there are three main parts to accuracy: The Person, The Rifle, The Research.

The Person

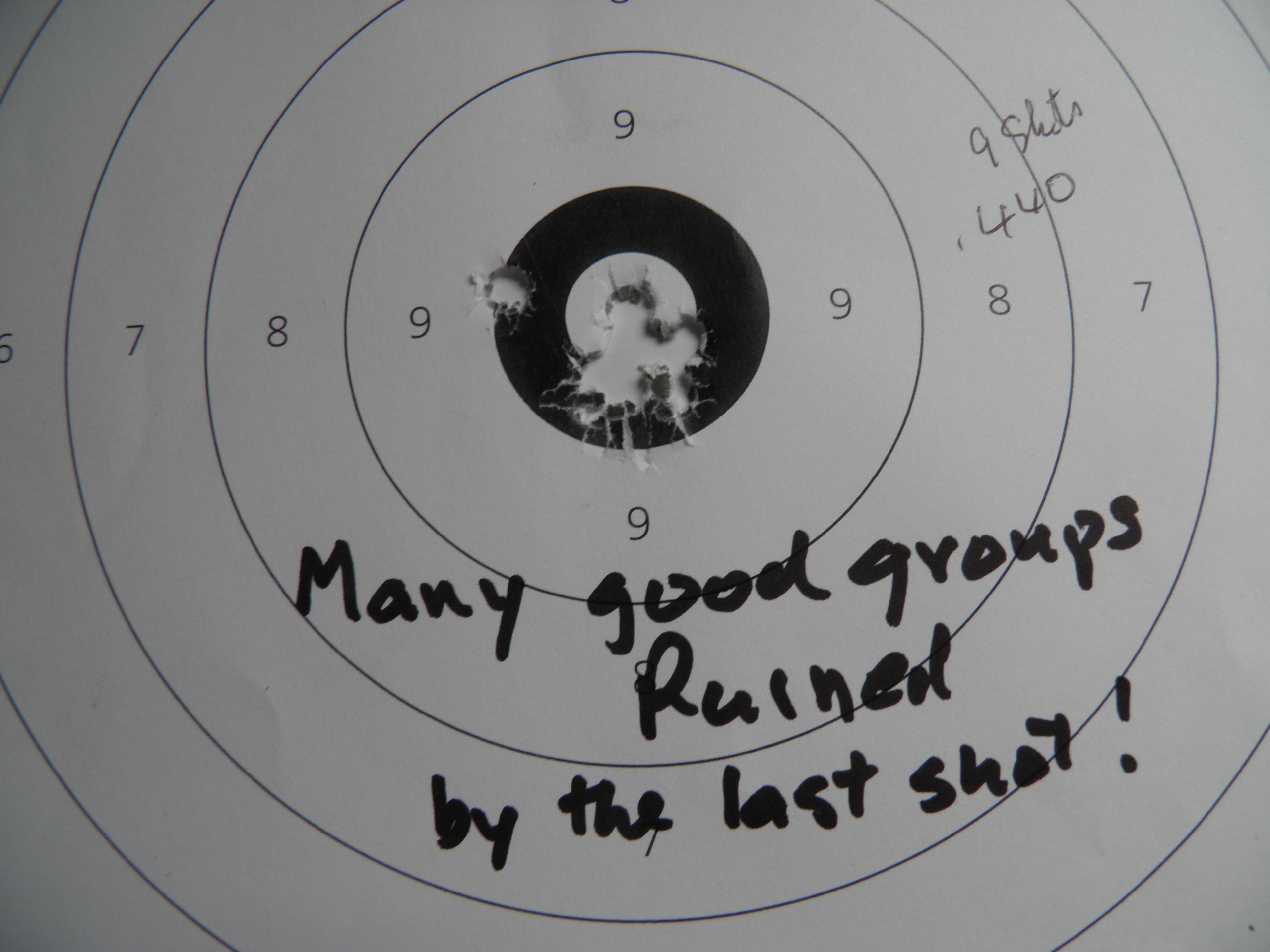

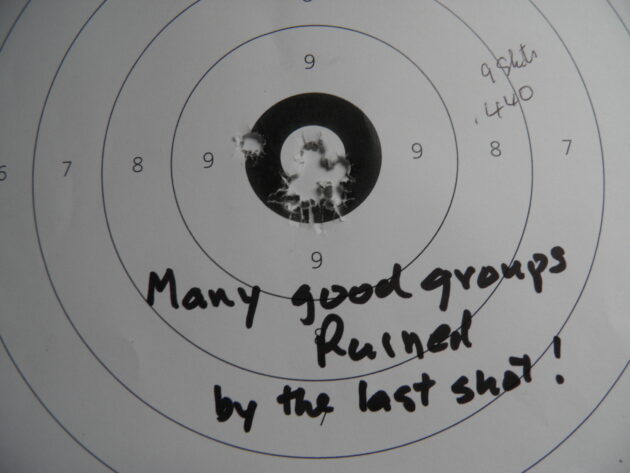

The first and simplest requirement is a stable rest both front and rear so the rifle sits without being held on target. The fewer muscles involved, the less influence they will have on the deflection of the shot. You should get away with only sufficient effort to be able to work your trigger finger without twitching. Sounds easy, but your control of the rifle must be consistent for EVERY shot. And, particularly, don’t relax or get excited about the last shot.

The two other things to consider are the means of delivery and the bullet components.

The second thing you must decide is what your rifle will be used for primarily.

If it is for game hunting the choice is relatively easy – most major manufacturers produce competent rifles with acceptable accuracy with factory ammo. They should be able to put a projectile into a four-inch circle at 300 yards. You only need to try different brands and loads to find the best. By reloading the cartridges yourself, apart from the initial outlay for press, dies, brass length trimming gear, scales, primers, powder and projectiles, loading becomes progressively less expensive per bullet than factory ammo, but not much. All you gain is the extra accuracy.

If you are ancient like me and have decided to chase accuracy, then there is a choice. Short range up to 300 yards (traditional imperial measurements dominate in shooting sports) or out to 1,000 yards.

Fortunately, we don’t have the longer ranges, so look at the 100 to 300 yard distances.

A sporting rifle with a light barrel might work for shorter strings of shots, but don’t expect total accuracy as the barrel heats up. You might do better with the heavy stainless steel barrels, but would you want the extra weight in the hills? A poor shooter can win matches with a good barrel, but a good shooter can never win with a poor barrel.

Decision Time – The Rifle

Can you justify the expense of a purpose-built rifle for which you will have infrequent use? I priced a new custom rifle built up from specialist engineering firms for action, barrel, trigger, stock. I stopped at $10,000.00, with still a scope and reloading components to add. So I bought a second-hand rifle with a new barrel from a top New Zealand shooter who had replaced his with a new model.

This is a 6mm PPC. That uses a cartridge developed from the Russian 7.62 X 39 for use in the AR platforms (military style semi-automatic). It was developed into the most accurate bolt action single shot rifle, which dominates in international competition.

One of the other developments from this cartridge is the Grendel 6.5mm. The cartridge is the same overall length, but the neck is shorter, giving a greater powder capacity for the heavier projectiles.

The 6 PPC uses projectiles in the 60-70 grain range, and the Grendel, from 100-140 gr, with the best combination around 120/130 grains. A grain is one seven-thousandth of a pound (454 g). My Grendel started as a standard light barrel sporter with good accuracy over a small number of shots in a string, but not for a longer match. I worked to improve it so now it is a custom build – only the bolt and action are original. It was a challenge both mentally and financially.

Research – Tightening the group

A Competition Rifle must be able to shoot groups of less than one quarter of a minute of accuracy (MOA). A minute of angle represents about one inch at 100 yards, two inches at 200 yards, and three inches at 300 yards.

The groups are measured by subtracting the diameter of a bullet from the spread of the furthest apart shots. This allows for different calibres to be compared. Anything around .100 inch spread (five shots in one small hole at 100 yards) is well in contention and a .250 inch spread is competitive.

How to get there? Trial and error, with much trial and a lot of error!

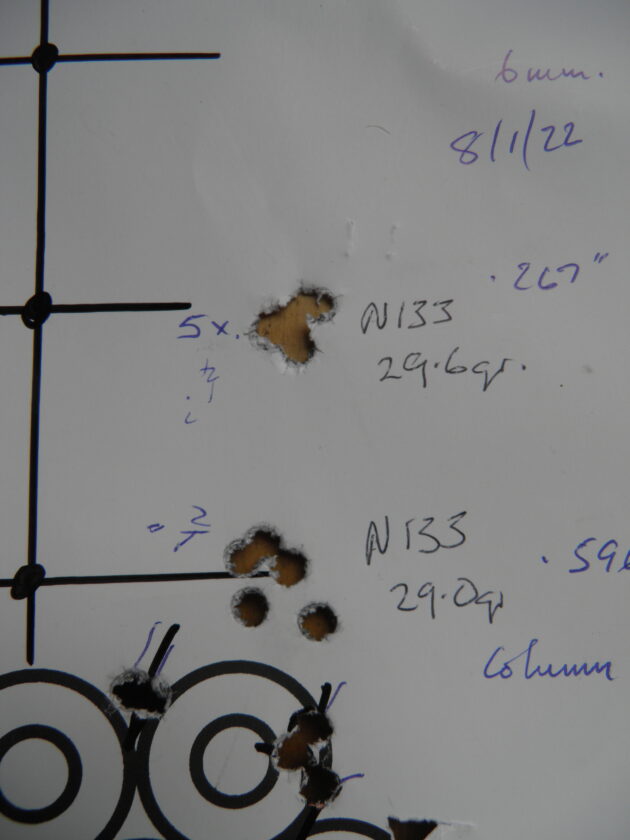

The six mm (6 mm) PPC was simple as I got advice from fellow competitors and that reduced the number of trial loads. The Grendel is different as no one else in our group has used one for competitions.

Powder and projectile manufacturers have trialled loads extensively and give recipes for all the suitable bullet weights and a minimum and maximum load for each. The lighter the projectile, the faster burning the powder. The heavier the projectile, the slower burning the powder.

The case capacity is usually given in the specifications so you choose a powder that nearly fills the case. This gives a more even ignition and burn and therefore pressure. Fifty thousand to sixty thousand pounds per square inch is not unusual. With the 6 PPC the most appropriate powder (hard to come by) is a Vihtavouri N133 with a maximum load of 28 grains.

This has proved to be too light, producing a vertical string of hits, so one has to exceed the recommendations – with care – until a small round group results. (I use 29.6 grains and another mate goes up to 30.2 grains – well over the suggested maximum).

So to be methodical, you start with the minimum and load three rounds and increase the powder by a quarter grain until you reach the maximum. The groups should narrow down in size until you reach optimum. Exceed the optimum and the groups spread sideways. The best load will probably be the maximum given plus up to one and a half grains more.

If you exceed the maximum given you must check every case for signs of pressure – a flattened primer or hard to open bolt. If that happens, back off and stop. Nasty things can happen with excessive pressure.

You should notice a range of groups of similar size and impact points on the target. This is where experimentation really begins. You take the middle one – for example 27.0, 27.5, 28.0 – and start to experiment with bullet seating depth.

First, find the maximum length. I start a projectile into an empty resized case and put it in the chamber and force the bolt closed. This seals the projectile where it touches the grooves (lands). Length is noted and projectiles are then seated into the loaded cartridges in multiples of .003 inches, this being the vibration mode of a typical barrel.

The long thin Extra Low Drag (ELD) projectiles like to be seated close to the lands, so I would start at .009, .015 etc; for the Grendel .030 and .042 seem quite good with a 120 grain projectile with 28 grains of powder (1 grain over maximum).

The important thing is to record every recipe and the results so you can compare them and return to them in the future. It can take up to 60 or 70 trial loads, or you might fluke it the first time. That is the challenge. However, as I wrote earlier, all can be confounded by failing to use exactly the same technique for every shot. One inconsistency can produce a ‘flier’ (loose shot) which completely ruins a group and makes diagnosis difficult. Ultimately, accuracy rests with the squeezer of the trigger!