Trooper Tom, 50060, from West Melton had a vision; it was his brother Jim, his younger by three years and 364 days. Jim was in uniform, he was soaking wet, he didn’t say, or do, anything, he simply vanished almost as instantly as he’d appeared, leaving Tom with a bad, bad, feeling, so much so that he wasn’t nearly as surprised as the rest of the family when the telegram arrived: Killed in Action, October 12, 1917 at a place bearing the name Bellevue (Nice view) Spur, a little rise overlooking what had once been a town called Passchendaele, now in ruin.

It was that nightmare weapon, the machine-gun, which cut most New Zealanders down that day, a piece of devilish genius raining death on an industrial scale upon the band of agricultural brothers from the opposite side of the world. Housed mainly within very strong concrete fortifications which came to be known as pill-boxes, arranged diagonally in a zig-zag pattern across the German front, some of which would survive direct hits from artillery shells, the little dungeons of death had to be flanked: that was their vulnerability. Then assaulted, one by one, by teams of infantry, but first the infantry had to get to them across masses of barbed wire fixed in front of the little forts. Sometimes the dense and dangerous protective wire, designed to slow down any attack, was arranged row upon row presenting a fifty metre swathe for assailants to cut through, among other obstacles to their approach.

The grim scene is described in the History of the Canterbury Regiment:

“Party after party made the attempt from either flank; and though some got as close as fifteen yards from the pill-boxes, none succeeded in reaching them. There can be no praise too high for these troops, who, with the example of failure after failure before them, undauntedly threw themselves against the impenetrable wire, raked by the heaviest machine-gun fire.”

Such bravery, such loss, such waste, cannot be measured, even a century later, nor forgotten. Nor can we forget that the men behind the German guns were brothers too, and fathers, sons who would have preferred to be home in Saxony, Bavaria, Westphalia sharing a beer, perhaps smoking a pipe in front of a fire, rather than confronted by colonials determined on taking German lives in the wet, cold and bloody landscape of Ypres.

Nor should we forget the political buffoonery that placed the New Zealanders in such an impossible position that day: the ‘higher-ups’ who cared more for back-slaps than any body-count.

Within a year Tom from West Melton was transformed in ways he wouldn’t have believed possible. He would be part of the 230-strong ‘2nd New Zealand Machinegun Squadron’ attached to the Australian Mounted Division and fighting alongside French cavalry in the somewhat eclectic “Australian Light Horse 5th Brigade” consisting of the 14th and 15th Australian Light Horse Regiments, the New Zealanders with their arsenal of 12 ‘Vickers’ on machine gun duty, the French ‘1er Regiment Mixte de Marche de Palestine et Syrie’ (RMMR) cavalry along with gunners from Merry England: ‘B’ Battery, Honourable Artillery Company.

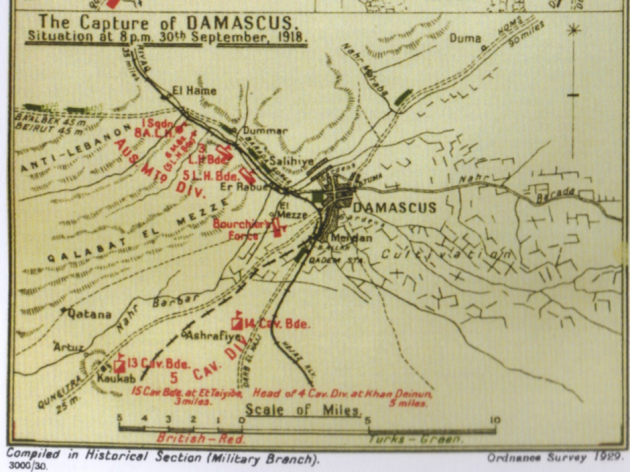

He would find himself at the top of a gorge, 300 feet above the Barada River, by the late afternoon of September 30th, 1918, just outside Damascus. The city was about to fall following one of most successful coordinated assaults of the war, some say of history, sweeping the Turks from 400 years of occupation in the Holy Lands, smashing the vaunted Turkish 4th, 7th and 8th Armies in the process of a whirlwind campaign, a complete reversal of Gallipoli but which would never remove that stain, or hardly be remembered.

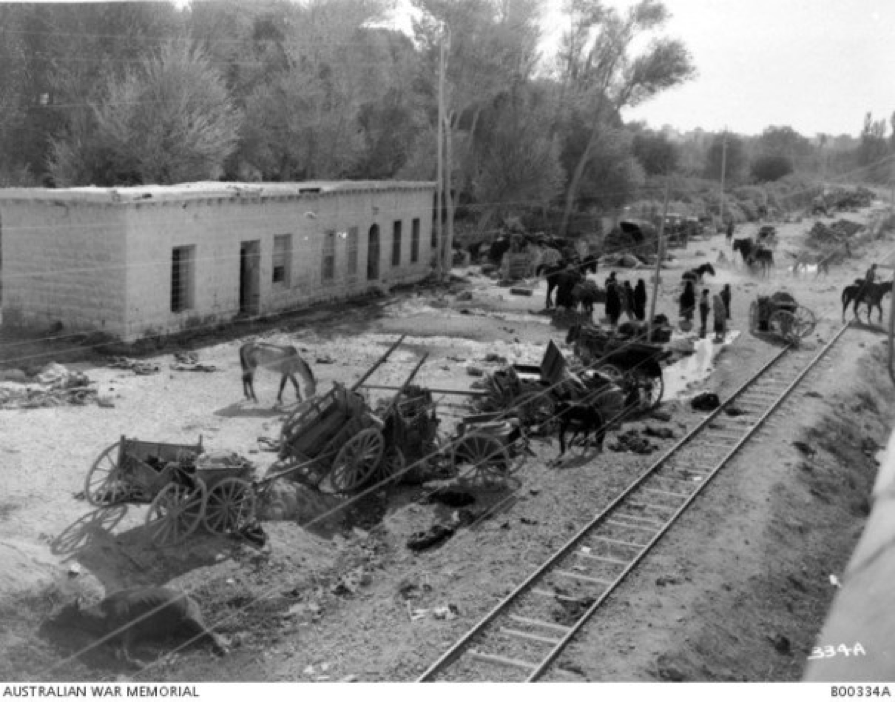

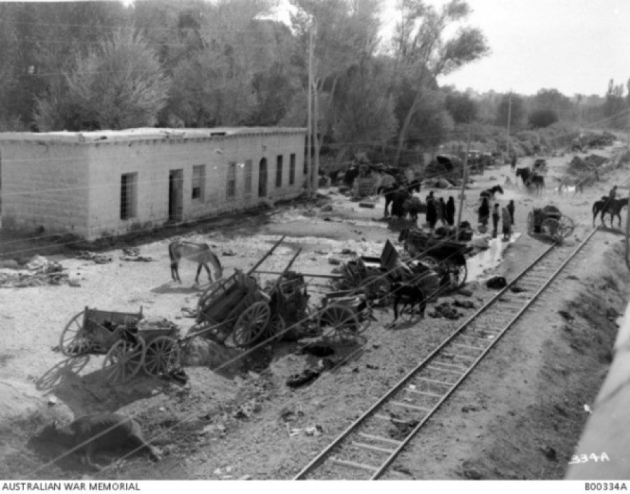

Below Tom’s fellow machine-gunners, below the RMMR, below the 14th and 15th ALH and below the Aussie 3rd Light Horse Brigade who had also arrived and spread along the ridges of the gorge in large numbers, were ‘tidal waves’ of enemy troops, animals and equipment, motor lorries and trains carrying the majority of the Damascus Garrison, along with remnants of the three Turkish armies and their German allies away to hoped-for safety, to re-group and fight another day.

The Australians, instructed to prevent that happening, signalled the enemy to stop and surrender, which received the rude reply of a hail of bullets from German guns mounted atop the train carriages and on the lorries of the enemy column. That was a huge mistake.

“The head of the column was felled, and, as the unfortunates behind kept pressing forward, they were mown down as by some invisible scythe. Horses and men went down together in hundreds and died in one tangled bleeding mass. Many fell into the river and were drowned. The Germans fought desperately from the tops of lorries and from a train with their machine guns, but, seeing not where to fire, their shots were wild, and they too went down in the slaughter. The water in the MG jackets hissed, and bubbled, and steamed. The barrel in one of the guns was so hot that it bent like a crooked stick. Australian Hotchkiss guns and rifles joined in the work of destruction. Above the rattle of the machine guns and the roar of the river, the cries of anguish and despair swept up from this valley of death. With every avenue of escape cut off, the stricken survivors surrendered to their unseen foes.” – Sergeant M. Kirkpatrick, 2nd New Zealand Machine Gun Squadron attached to the 5th Light Horse Brigade

Captain Ron McKenzie, commanding the Machine Gun Squadron that day, changed the wording in the unit War Diary entry regarding enemy losses inflicted from “heavy” to “severe” casualties, continuing “which resulted in the capture of many wagons, machine-guns & a train.” While the 3rd Light Horse Diary states the column below them was “annihilated”. The 5th Brigade took in 4200 prisoners after the guns fell silent while the number of those who died during the onslaught, it appears, wasn’t recorded, there was simply ‘seven miles of death’, others note ‘it took a large contingent of German prisoners-of-war 10 days to bury all the dead’ as a result of foolish intransigence and ill-judgement.

Early next day the ALH 10th Regiment representing the 3rd ALH Brigade would accept surrender from the Mayor of Damascus without resistance, although that honour had been pre-arranged as to be performed by the master tactician, but better self-publicist, T E Lawrence (of Arabia) and his Arab troops as a political statement. So the ‘surrender’ was re-performed for posterity three hours later, after Lawrence arrived, but not before overjoyed crowds of Damascans feted the dusty ‘Diggers’.

“They rode with drawn swords, dusty and unshaven, their big hats battered and drooping, through the excited people of the ancient city, with the same easy casual bearing, and the same quiet self?confidence, which mark their bearing on their country tracks at home. They ate their grapes, and smoked their cigars, and missed no dark smiling eyes at the windows; but they showed no excitement or elation.”

Trooper 50060 was not given to emotion during his life and like so many others never spoke of the ‘Great War’, so it’s impossible to know what he made of the suffering he felt or witnessed. He may have thought of his brother, he may have thought of his mother; ill in Riccarton, he may have dreamed of being back on his land at West Melton, but realistically, his thoughts were more likely trained on the next ‘job’ lined up for him and his cobbers, and how best they be getting on with it.

“Soon after 7 o’clock they were clear of the city and in vigorous pursuit of the enemy columns in flight towards Homs.”

With the fall of Damascus the ‘Ottoman Empire’ was very close to collapse, and would soon be but a memory.

To the memory of the fallen, and of the maimed, and to all those who served their country.

Lest we forget.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.