At the time of writing this week’s column, I don’t know the identity of the new Leader appointed by the Caucus of the National Party, but I DO know the most important challenge the party needs to face up to if it hopes to become the next government of New Zealand. The party needs to restore our traditional democracy currently under threat by Marxist Jacinda Ardern and the mendacious cabal who have already begun their underhanded annihilation of the unity and open governance we have enjoyed for almost the past two centuries.

How this has come about and what it will mean is covered in today’s essay, thanks to the in-depth research of a colleague who wishes to remain anonymous.

The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) forms a triangle with the 2019 He Puapua report and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. This important association could affect New Zealand’s future significantly.

UNDRIP Facts

UNDRIP is a Declaration: a UN legally non-binding instrument encouraging nations to support particular issues. UN treaties and conventions, requiring signature and ratification, are legally binding instruments amongst states. But UN non-binding legal instruments have no authority over national law. Each country decides if and how to implement them, and responsible governments scrutinise all legal instruments for possible pitfalls.

UNDRIP, signed in 2007 by 144 countries, was inspired by the Rio 1992 Earth Summit which defined Agenda 21, the UN’s 1992-2015 Plan. This triggered the Green movement to protect endangered environments, natural resources and indigenous peoples.

In 2010, John Key’s government signed UNDRIP (apparently against Helen Clark’s advice) as part of the National – Maori Party coalition. Action continued during Chris Finlayson’s tenure as Treaty Minister. Since 2017, Labour has initiated the He Puapua Report and legislation involving co-governance in the areas of local government, health (a separate ministry) and water management (with others proposed, such as justice).

Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US originally declined to sign UNDRIP as incompatible with their governance and legal systems. All have peoples classed as “indigenous” or “first nations” and are viewed under UNDRIP as colonising powers. Each approaches UNDRIP differently. Australia endorsed the instrument in 2009. The US has expressed support. In June 2021, Canada passed federal law C-15 to launch a national UNDRIP action plan.

In 2010, New Zealand signed UNDRIP. In 2016, the Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation produced the Matiki Mai Aotearoa report (a preliminary version of He Puapua) with funding from the McKenzie Trust and from a UN grant to small projects. This group, promoted by the Iwi Chairs Forum, was led by Margaret Mutu, an Auckland University Sociology professor, with Moana Jackson, a lawyer and indigenous peoples’ advocate, as convenor. As of 2021, the He Puapua report has no clear status, and no citizens information campaign or discussion has taken place. The government avoids comment, and National’s “Demand the Debate” initiative in June 2021 was short-lived.

Importantly, UNDRIP implies the superiority of indigenous law and the right of veto by indigenous peoples over the state (Articles 19 and 32). Thus, it was deemed incompatible with New Zealand’s democratic governance. Though UNDRIP may state aspirational goals, only a national government can decide to implement them. A country can withdraw from this arrangement at any time if its government – or citizens – so decide.

The Triangle: UNDRIP, the Treaty of Waitangi and He Puapua

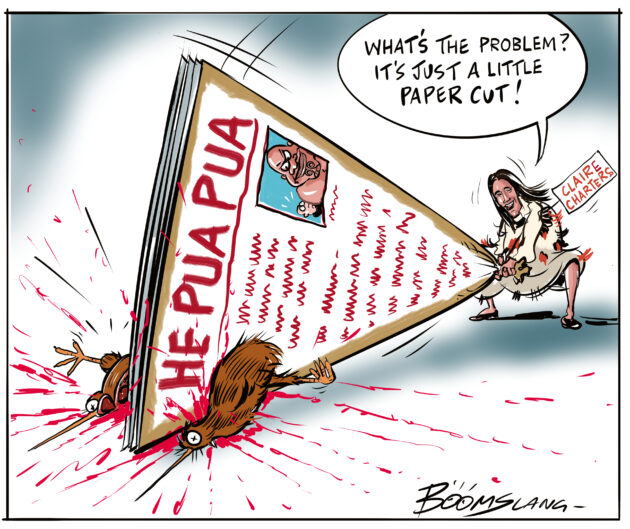

How does this operate? He Puapua explicitly seeks a rupture of the usual political and social norms by proposing co-governance by Maori and Europeans by 2040 (the Treaty of Waitangi bicentenary). Its Introduction states, “We hope that the breaking of a wave will represent a breakthrough where Aotearoa’s constitution is rooted in te Tiriti o Waitangi and the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” New Zealand’s Westminster system of democratic governance for all citizens has no mention.

Lead author, Claire Charters, is an Auckland University Constitutional Law professor and UN adviser on the rights of indigenous peoples under international law. Although the report is described as a set of talking points, its recommendations are advancing steadily through legislative precedents.

Who are the parties to approve He Puapua? Who is the “Crown” today? Is it the Queen, the New Zealand non-Maori population or the government of the moment? Does New Zealand’s approximately 84% non-Maori population have any role or voice? Could the Maori-only veto over legislation mean superior authority in an unequal partnership?

Citizens must discuss and approve He Puapua because – if voted – this could become the formal constitution of New Zealand and predicate all future laws. Why is this critical step ignored?

In line with He Puapua, the Labour government is legislating for increased Maori representation and control (via veto) in specific domains. According to Minister Mahuta, this is justified by the Treaty of Waitangi’s settlement process which “…. has already legislated for various rights and interests of Maori.” (NZ Herald, 3 November 2021). Is this totally accurate? Further obligations are evoked under “Tikanga”, Maori cultural appropriateness. Is this law or custom?

Clearly, New Zealand must address its involvement with UNDRIP and its links to the Treaty of Waitangi and He Puapua in ways that satisfy all New Zealanders. This is the minimum expectation in a democracy.

Since 2014, Professor Mutu of Auckland University has chaired the Monitoring Mechanism – a Maori body independent of government that reports to the UN on New Zealand’s compliance with UNDRIP. Are New Zealanders aware of this group’s role over seven years through public reporting? A UN Declaration never dictates to nations. Have factions used this UN international and non-binding legal instrument to advance critical issues which require prior and full citizen debate and even a further legal review of the Treaty of Waitangi?

In 2019, Canada’s Premier, Justin Trudeau, and his Federal Minister for Justice, Jody Wilson-Raybould, clashed: national unity and the rule of law were pitted against indigenous interests and proposed control of economic resources. Could a similar conflict threaten New Zealand?

Since 2010, politicians have been aware of this accelerating action – but are citizens fully informed? Now, many serious and interrelated questions could emerge – possible withdrawal from UNDRIP, repeal of inequitable legislation, review of the Treaty of Waitangi and even MMP’s suitability for New Zealand.

All New Zealanders should demand consultation on these issues as their right. Further delay could see irreversible action. UNDRIP is part of a complex triangle.

Up to this stage of the Ardern government’s second term, public attention and that of most of the bribed news media has been focused on the Covid-19 pandemic, the merits of vaccination, and so on. Inevitably, this has commanded most of the attention of the Parliamentary Opposition, allowing Ardern and her out-of-control Maori Minister, Nanaia Mahuta to begin stealthy implementation of He Puapua.

They have done this by abolishing the right of local bodies to decide whether or not to have compulsory Maori representation. They have also centralised the administration of health not just by dismantling DHBs but by creating a separate Maori Health Authority.

The new authority will have a right of veto over decisions made by the health administration that would cater for the vast non-Maori majority. There are also now proposals to give Maori similar rights in respect of water and protection of conservation areas and native plants.

For another informed view on these issues read Dr Muriel Newman’s article “The Fatal Flaw”.

Meanwhile, for the sake of its own survival and for the sake of the future of our country, it is imperative that the new leadership of the National Party tackles as a matter of urgency and priority the duty of exposing and opposing He Puapua and all its tentacles.

The rest of us need to shake off our lockdown apathy, get over the fear that Ardern is using to distract us with while she unravels her Marxist plots, and make her ragamuffin MPs realise that if they don’t themselves dump He Puapua, we’ll dump them – by a landslide.