Josh Van Veen

Victoria University Of Wellington – Te Herenga Waka

democracyproject.nz

Josh Van Veen is former member of NZ First and worked as a parliamentary researcher to Winton Peters from 2011 to 2013. He has a Masters in Politics from the University of Auckland. His thesis examined class voting in Britain and New Zealand.

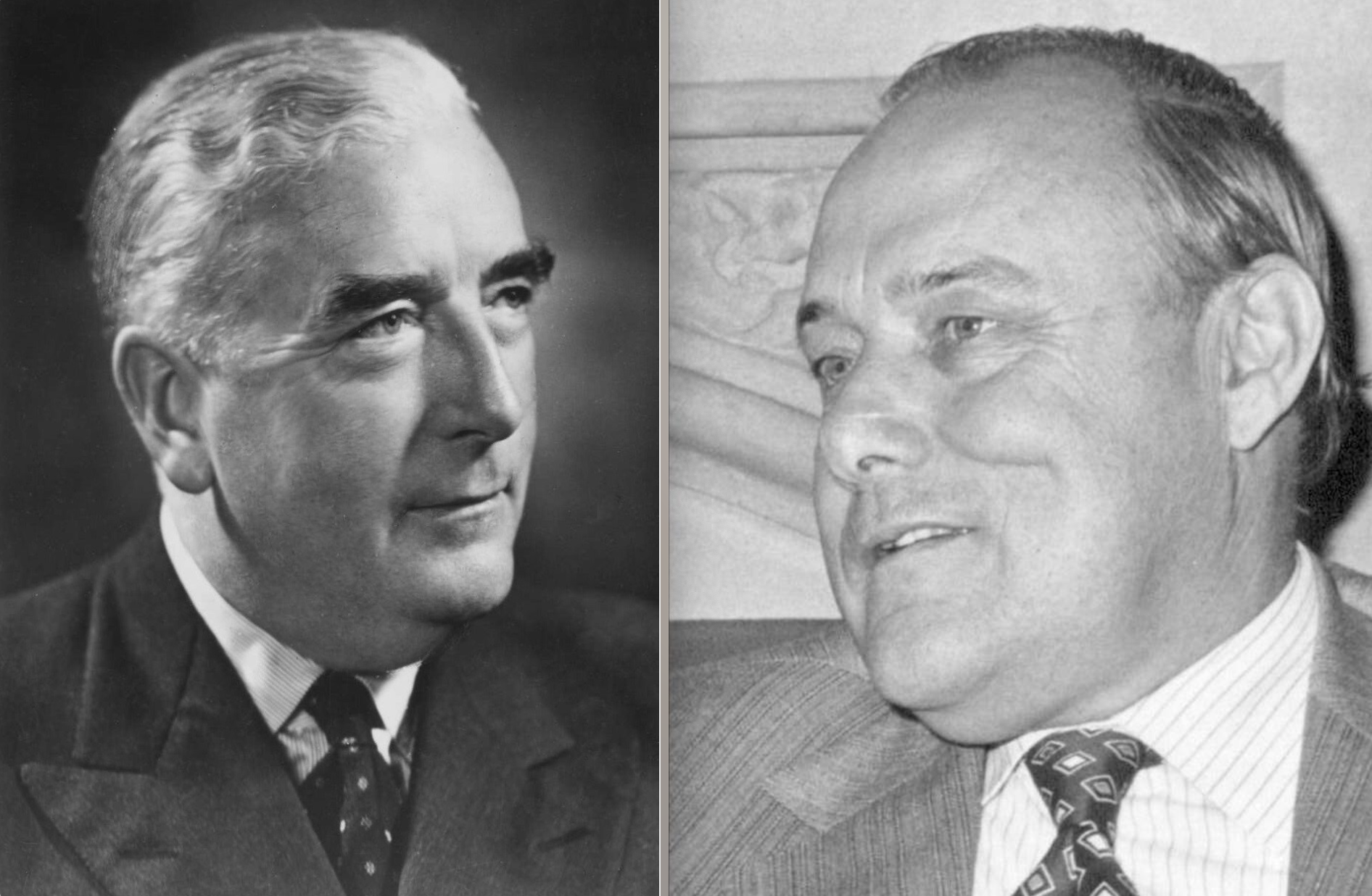

On 22 May 1942, a failed prime minister sat down to record what would become one of the most influential and celebrated political speeches in Australian history. The previous year Robert Menzies had dramatically resigned after Federal MPs vetoed his grandiose plan to leave Australia and sit in Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet. Menzies’ party, the United Australia Party, was on the brink of collapse.

The humbled backbencher now depended on a weekly radio slot to keep his political career alive. But in a powerful oration, rich with meaning, Menzies redefined Australian politics for a generation. As the political historian Judith Brett explains in her critically acclaimed book, Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People (1993), the speech was a brilliant response to growing class divisions and the rise of Labor.

A conservative in the liberal tradition, Menzies argued for a politics based on home life rather than the workplace. His listeners were encouraged not to define themselves according to wealth or status, but to identify with certain moral qualities. After all, it was the ‘forgotten people’ working hard to pay the mortgage and raise a family, who were the backbone of the nation. And they were in danger of ‘being ground between the upper and nether millstone of a false class-war’.

By 1949, there were enough forgotten people in suburbia to return Menzies to government as leader of the new Liberal Party. He would go on to become Australia’s longest serving prime minister. Seventy-two years later, the Liberals remain a formidable political force. Menzies’ ideas are still a source of inspiration for the party of Scott Morrison and Tony Abbott. As Morrison put it in a 2018 speech, ‘It’s about what you’re for. Not just what you’re against.’

The Liberals’ 1949 victory coincided with the rise of another ‘centre-right’ party in Australasia. Just ten days earlier, the New Zealand National Party had also won power for the first time. Its leader was the aggressive Sidney Holland, a Christchurch businessman, who came to prominence as a right-wing activist in the 1930s. He famously denounced the social welfare policies of the First Labour Government as ‘applied lunacy’.

Holland shared a basic outlook with Menzies. He believed in a ‘sturdy New Zealand philosophy of independence and self-reliance’ that elevated the individual above class. But despite his practical wisdom, Holland was no thinker. He did not have the imagination to do what Menzies had done for the Liberals. There was no grand historical narrative to explain the rise of National; no creation myth.

Rather, the National Party grew up believing that it was simply born to rule. Holland and his successor, Keith Holyoake, became symbols of power and not much else. They roundly defeated their opponents in election after election but, more often than not, the policies of National and Labour were indistinguishable. It was the archetype of ‘strong leadership’ that embedded National in the public mind.

Every successful National prime minister, from Holland to Key, has dominated politics through sheer force of personality. They are remembered not for legislation or policies but their ability to inspire confidence and keep the wheels of government turning. If there is an exception to that rule, it is the one leader whose legacy National would rather forget.

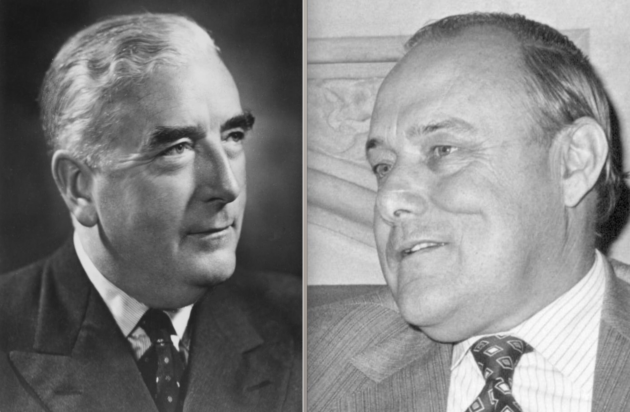

Robert Muldoon is often regarded as one of the country’s worst prime ministers. He alone is blamed for the turmoil of the 1980s: rampant inflation, racial disharmony, violence during the Springboks’ tour, and the foreign exchange crisis of 1984. The latter gave impetus to, if not a pretext for, the controversial reforms of the Fourth Labour Government.

In the political lexicon of 21st century New Zealand, ‘Muldoonism’ is a byword for economic illiteracy and megalomania. To be compared to Muldoon is perhaps the most grievous insult one can make against a sitting prime minister. According to their critics, Helen Clark and John Key were both ‘like Muldoon’. The charge has even been made against Jacinda Ardern.

However, the caricature of Muldoon betrays a shallowness in New Zealand public life. He was a well-read, intelligent, and thoughtful man, who offered himself for analysis more than any other modern prime minister. A prolific writer, he was the author of five books and numerous articles, not to mention speeches. He was also a talkback radio host; his final public statement a heartfelt call to the now defunct Radio Pacific.

In the 1970s, Muldoon defined the National Party both culturally and intellectually. He still does. The shift from economic nationalism to a market liberal orientation post-1984 has obscured the continuing influence of Muldoon’s political philosophy on New Zealand. His bestselling book, The Rise and Fall of a Young Turk (1974) was the most authoritative statement on the motivations and outlook of a National partisan in the 20th century.

Muldoon evoked the quintessential New Zealand dream. He imagined a country in which there was no poverty, Maori and P?keh? were equal, and anyone who worked hard could own a house. The people who inhabited it were like him; simple but fair-minded, and fiercely independent. The country Muldoon idealised was affluent, middle-class, and unashamedly P?keh?. It was built on values forged in blood and sweat – in the bush, on the farm, and at war.

It was about equality of opportunity rather than outcome. Society would give you an education as far as you could go and look after you in hard times. The rest was up to individuals. But in sickness and health, the government had your back. Even if it were monocultural, Muldoon’s New Zealand was founded on a belief in equality between the races. M?ori had fought and died alongside P?keh? in two world wars, now they played rugby and drank beer together. There was no need to complicate these relations further.

Only subversive radicals and incompetent politicians threatened to undermine Muldoon’s New Zealand. But it was the inexorable march of globalisation that proved fatal. In the mid-20th century, New Zealand was still a pastoral economy. Dairy, meat and wool made up 60% of export revenue during the 1960s, with most produce destined for the easy and lucrative British market. As a result, New Zealanders enjoyed the highest living standards in the world.

It turned out to be a fool’s paradise. The sudden collapse of wool prices in 1966, and Britain’s decision to join the European Economic Community, exposed New Zealand to world-historical forces that no government can control. Farmers lost income, unemployment began to rise, and so did inflation. Muldoon was the only politician who knew what to do. Intellectually, he understood the need for diversification and competition. But he refused to sacrifice the egalitarian myth of post-war New Zealand.

Muldoon fell back on the language of economism. Charts and tables were his go to as he made the case against free market policies. But it was a concern for ‘ordinary people’ that motivated him. He promised to make New Zealanders feel secure again. This rested on a simple yet contradictory notion that New Zealanders could have independence and freedom while also relying on the state for protection. Muldoon’s politics were an attempt to defy reality. For a time, he succeeded.

While commentators fixate on the political economy of Muldoonism, they overlook the cultural meaning behind it. The attitudes and values that Muldoon gave expression to are still deeply ingrained. Most of us want to believe that New Zealand is exceptionally humane and tranquil. We prefer not to see our worst attributes. It is much easier to deny racism, for example, than it is to confront our prejudices.

And yet it is the betrayal of the egalitarian myth, or the failure to realise it, that most often leads to political change in New Zealand. The National Party must appeal to fairness if it is to win power again. Whether that means enjoying the fruits of your labour, or lending a hand, our nationhood depends on the belief that New Zealand is a modern day Arcadia in the South Pacific.

Ironically, it is National’s most hated leader who understood this simple truth better than anyone else. The fact that no government has dared to cancel Muldoon’s universal pension scheme – audaciously called ‘National Superannuation’ in 1975 – is a monument to his success. The qualities he admired most were ‘genuine humanitarianism’ and ‘intelligent pragmatism’. His old party should embrace that legacy.

Muldoon is the closest we have to a Menzies.

This article can be republished under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Attributions should include a link to the Democracy Project.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.