Some time back, I wrote about the earliest known images of Jesus. But what about his mother?

As historian Geoffrey Blainey says, Mary’s cult was virtually unknown in the the first century of Christianity, but within a few centuries, “veneration of Mary was sufficiently widespread for the Council of Ephesus to grant her the title of Mother of God. Veneration of Mary grew in popularity for centuries more, peaking in the 12th century.

Artistic depictions of Mary, who like Jesus is not physically described in the Bible, similarly reflect the traits the artist wanted to particularly emphasise. From nurturer to loving mother to protector and intercessory with God, Mary’s iconography evolved through the first millennium of Christianity.

Dura-Europos Church, Syria, 2nd century

The Dura-Europos Church is believed to be the oldest Christian church known. Although the fate of the Church itself during the ISIS caliphate is unknown, fortunately perhaps, the Yale archaeologists who discovered it in the 1920s removed its frescoes.

One of the frescoes depicts a woman leaning over a well. At first it was believed to be the Samaritan woman who speaks with Jesus by the well, in the gospel of John. But more recent scholarship claims that it is actually a depiction of the Annunciation. Scholar Michael Peppard points out that 2nd century sources wrote that the angel Gabriel appeared to Mary as she drew water from a well. Details of the painting also suggest that it depicts an incarnation.

Madonna of the Catacombs, Rome, 3rd century

The Catacombs of Priscilla occupy what was once a quarry used for Christian burials, now buried under the Via Salaria in Rome. The painting believed to be of Mary depicts Mary nursing the holy infant. At a time when Christianity was still illegal, believers would bury their dead under the gaze of the nurturing Mother of Christ.

Madonna with the Magi, Rome, 3rd century

The adoration of the Magi is one of the most famous stories in Christianity, depicted to this day in billions of Nativity images at Christmas. This ancient image depicts most of the famous and instantly-recognisable images of the Nativity: the star, the three wise men (wearing distinctive Phrygian caps) bearing gifts, Joseph, and, of course, Mary nursing the infant Jesus.

Protectress of the Roman People, Rome, 5th century

As seen with the iconography of Jesus, by the 5th century, Christianity was the official religion of the mighty Roman Empire, and artistic representation evolved accordingly. Both Jesus and Mary are crowned in glory and exude authority and dignity.

Significantly, it is Mary who holds the viewer’s gaze rather than Jesus, who instead looks to his mother, now a protector as well as nurturer. Mary wears her now-traditional blue mantle, but in this case over a purple tunic: the ancient symbol of power in the empire. Mary has now assumed a traditional role in Roman religious worship as a protector: Salus Populi Romani, “Salvation of the Roman People”.

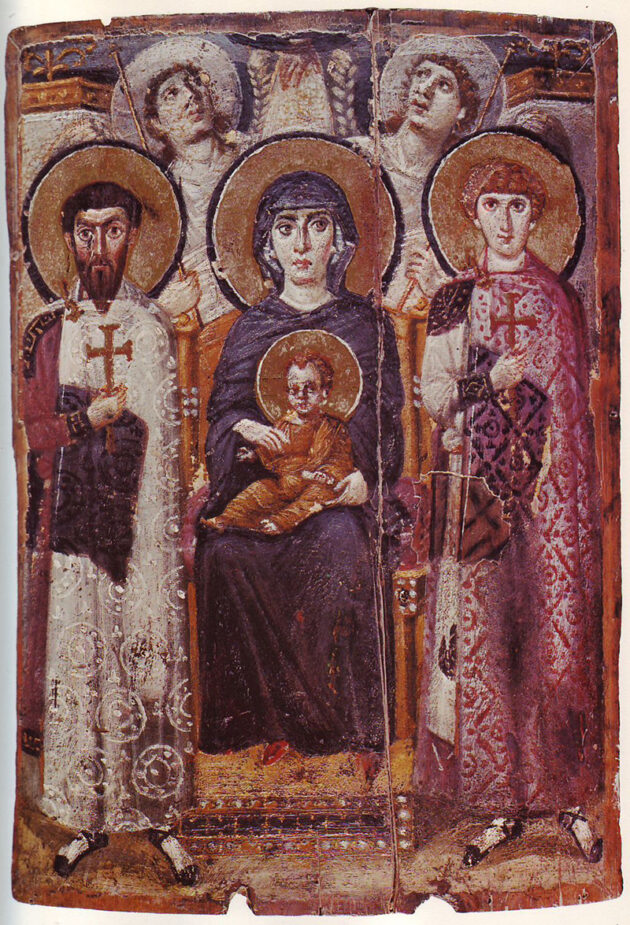

Madonna and Child enthroned among the angels and saints, Mount Sinai, 6th century

The 6th century Saint Catherine’s Monastery is the oldest continuously-inhabited monastery in the world. It was built on the site of a much older church built at the site of the Biblical burning bush. St Catherine’s was specifically granted protection from Muslim conquest by a treaty authorised by Muhammad. Consequently, it has an impressive collection of ancient manuscripts and artwork (including the Christ Pantrocator).

This icon – made using the “encaustic” technique, utilising coloured hot wax on wooden boards – depicts Mary and the Christ Child surrounded by saints (Theodore of Amasea and George) and angels.

Nativity, St. Catherine Monastery, Mount Sinai, 6th century

Another 6th century encaustic icon at St. Catherine’s is this Nativity. Even more of the familiar details of the Nativity are present: the manger, the animals, a shepherd, the heavenly chorus. Other gospel scenes are also shown, such as the angel appearing to Joseph.

Agiosoritissa (Mother of God), Constantinople, 7th century

As the cult of Mary developed, she progressed from being the Mother to a divine figure in her own right. In this rare example from 7th century Constantinople, Mary is depicted not as a mother (Jesus in absent) but as an intermediary between humanity and God. Known as the “Madonna the Advocate”, Mary in this icon would be prayed to for intercession.

Cover of copy of the Gospels, Germany, 8th/9th centuries

Centuries before Gutenberg’s printing press produced its famous Bible, scriptures were painstakingly reproduced by hand and bound with elaborate wooden or metal covers. This particular cover is carved from ivory and was used for a copy of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, an illuminated Gospel produced in the Lorsch Abbey in Germany, some time between 778 and 820: the time of Charlemagne.

The elaborate bas-relief carving shows Mary and Jesus as throned figures of power, surrounded again by saints and angels, as well as senes from the Nativity.

The codex was stolen from the Abbey during the Thirty Years’ War and broken in two, to sell off. The front half is now in Romania, while the back half is in the Vatican. The ivory front cover, however, resides in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Our Lady of Mellieha, Malta 12th/13th century

One of my favourite images of Mary is a relatively late one. It also holds a special significance for your author: its location is the family church for my wife’s family, who migrated from Malta in the 1950s. The church and its fresco are located in a grotto which was an ancient place of worship on the island. In Antiquity, the cave was a shrine to the nymph Calypso, famous from the Odyssey. But with the coming of Christianity in 60 AD, as described in the Book of Acts, it became a church. Tradition ascribed the fresco to St. Luke, but it is now believed to have been painted in the late 12th century. A 16th century overpainting was removed in 1972.

The fresco mixes Byzantine and Sicilian influences, as well as divine and vernacular elements. Robed in imperial purple and crowned with halos and the legend Mat Dei (“Mother of God”), Mary here also has Mediterranean olive features and an unsettlingly direct gaze.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD