It should be no surprise that there are no contemporary portraits of Jesus. After all, until the Middle Ages, portraits were relatively rare and even less often realistic likenesses – with the exception, perhaps, of the Greeks and Romans, who were apt to accurately portray Socrates’ famous ugliness, or Julius’ receding hairline.

Still, the fact remains that for a very long time, portraits were the reserve of the very powerful or very rich.

Jesus was neither. Indeed, as historian Geoffrey Blainey notes, the fact that we know anything about the life of a poor, itinerant preacher in a backwater province of the Roman Empire is remarkable in itself.

Unsurprisingly, then, the earliest known depictions of Jesus appear only in the century after his death.

Equally unsurprisingly, the oldest is far from flattering.

Alexamenos graffito, 1st century

Early Christians did not, it is fair to say, enjoy a wholesome representation in the Roman Empire. The Romans were not only annoyed by yet another restive Jewish mob disrupting the Pax Romana, but garbled accounts of the crucifixion and the doctrine of transubstantiation led to accusations of child sacrifice and cannibalism. An early slander was that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a black Roman soldier called Pantera (“all beasts”). Crucifixion was also a punishment reserved for the worst crimes.

Thus, the oldest known image of Jesus is a mocking graffito. Inscribed “Alexandro worshipping his god”, it depicts a Christian worshipping a crucified, donkey-headed god.

The Good Shepherd, 3rd century

Things had improved somewhat by the 3rd century. Although the Empire was yet to convert, under Constantine, the Christian religion was spreading even to the upper reaches of Roman society. Inspired by the metaphor of “the Good Shepherd”, many early Christian artists choose the image of the shepherd to depict Christ.

This image from the St. Callisto catacomb of Jesus carrying a calf on his shoulder, shows how early Christian artists incorporated existing Greek and Roman motifs. “Moskophoros,”, meaning “the bearer of the calf,” is motif in ancient Greek art which dates back to 570 BC.

Adoration of the Magi, 3rd century

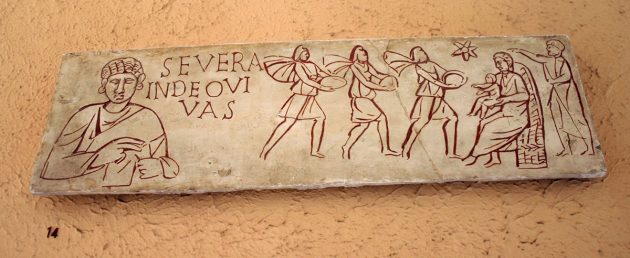

The adoration of the Magi, from the Gospel of Matthew, was another popular early representation of Jesus. This picture of the Magi adoring the newborn Christ decorated a sarcophagus dating to the 3rd century, which is now kept in the Vatican Museum in Rome.

Healing of the Paralytic, 3rd century

“Take up thy bed and walk”, the healing of a paralysed man, is one of Jesus’ miracles chronicled in three of the Gospels. It became a recurring image in Christian iconography. This depiction of the healing of the paralytic, dating to the 3rd century, was found on the baptistry of a long-abandoned church in Syria. It is one of the earliest depictions of Christ known to historians.

Christ between Peter and Paul, 4th century

By the 4th century, Christianity had come to enjoy state sanction in the Roman Empire. This fresco relates to some of the most powerful figures in Church history. Not only does it show Jesus between Peter and Paul, it was painted in a catacomb in Rome near a villa once belonging to the Emperor Constantine, whose conversion in 312AD was a turning point. The four figures in the lower part of the fresco are the martyrs Gorgonius, Peter, Marcellinus, and Tiburtius, who were buried in the catacomb.

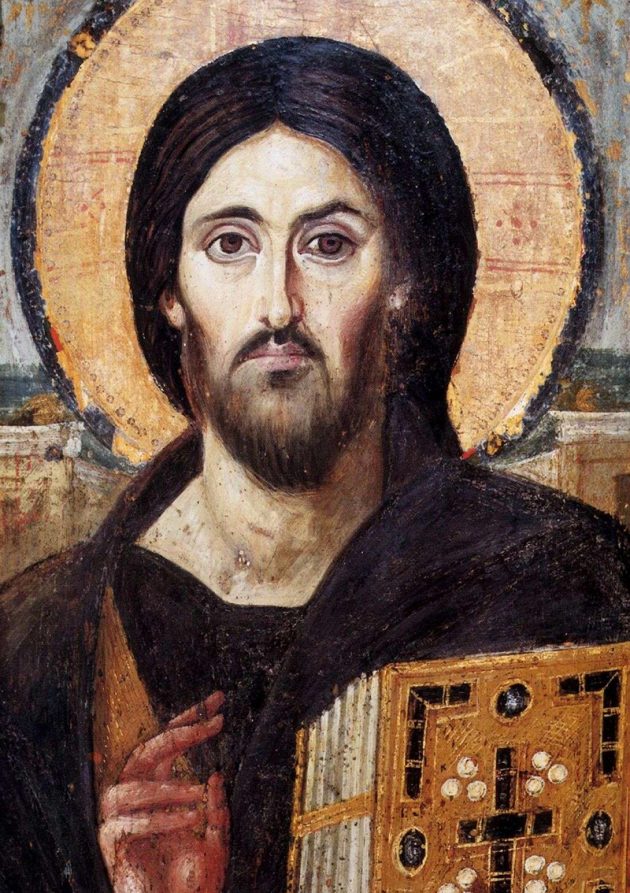

Christ Pantocrator, 6th century

By the Byzantine era, Jesus’ iconography had evolved to a figure of power and authority. Pantocrator (“he who has authority over everything”) is the Greek translation of two Old Testament Hebrew descriptions of God: “God of Hosts” (Sabaot) and “Almighty” (El Shaddai). The oldest known example of “Christ Pantocrator” was painted on a wooden board in the 6th or 7th century and is preserved in one of the world’s oldest monasteries, the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, in Egypt.

The painting is also noted for its different expressions on the right and left sides of Jesus’ face. This is thought to represent his double nature as both human and divine.

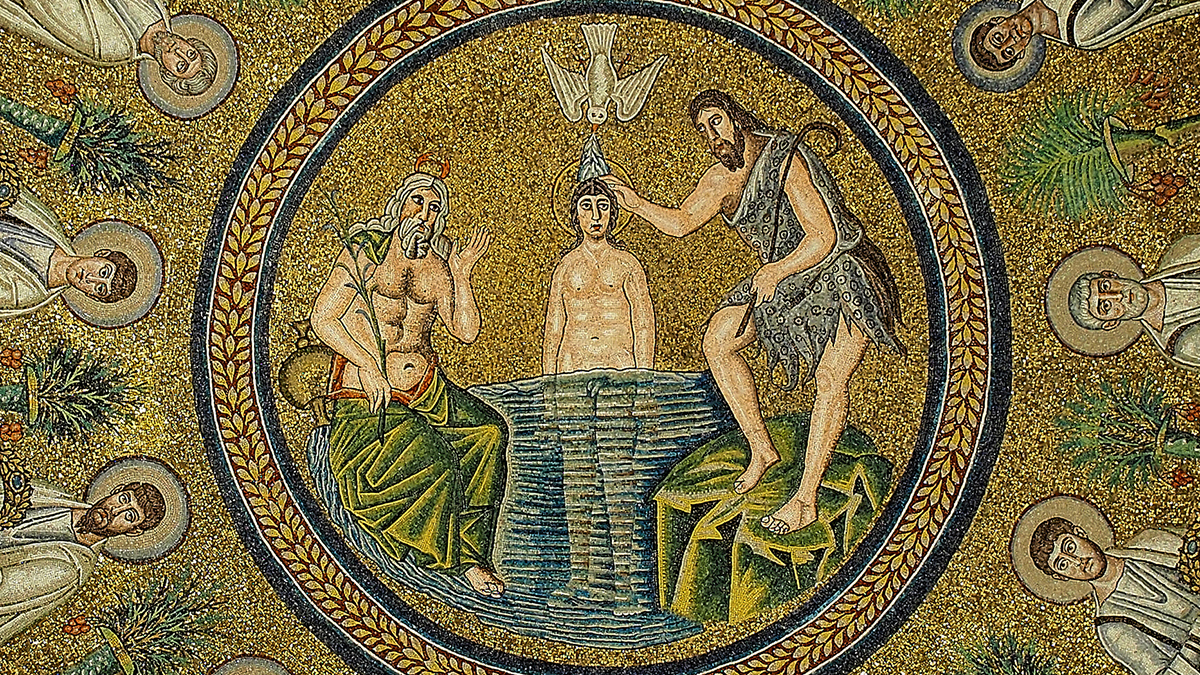

The Arian baptistry, 6th century

Arianism was a school of Christian thought which contended with Catholic orthodoxy for centuries. The central tenet of Arianism disputed Catholic trinitarianism by contending, most notably, that Jesus was not fully divine. Constantine himself regarded the issue as “minor theological claptrap”, which nonetheless stood in the way of uniting the Empire, but for theologians it was a vital issue. The Council of Nicaea declared Arianism a heresy, but its influence persisted for long after.

Very little Arian iconography remains. At Ravenna, “and almost nowhere else in Europe”, says Blainey. “We see Christ as Arius might have seen him”.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.