Bruce Moon

In the “Listener” for 25th February 2017, Vincent O’Malley wrote a contorted opinion piece on a significant event in New Zealand’s history – the tribal rebellion in the Waikato. “Middle New Zealand” readers of the “Listener” should not allow themselves to be misled by this story.

It would be easy to form the impression that the history of New Zealand began in 1840, so little do we hear of earlier events – of the brutal inter-tribal savagery with many people “daily dreading an attack from some unknown quarter” and “the ‘almost unbearable anxiety’ experienced by all Maori communities”.(1)

The Waikato themselves had been the victims in 1822 at Mataki-taki Pa when thousands of men, women and children, died in a merciless attack by musket-wielding Ngapuhi. In 1831, in turn, the Waikato were the attackers in Taranaki, an estimated 1200 dying when the starving defenders of Pukerangiora Pa broke and ran, many being spit-roasted in the ovens of the victors. (2)

It is not to be supposed that these leopards lost their spots all that quickly, their traditions of armed aggression being far from forgotten little more than one generation later.

In the 1850s largely on Missionary Morgan and Grey’s initiative, (3) the Waikato were doing well. They grew produce for the ready markets of Auckland and elsewhere, foodstuffs, be it noted, entirely unknown in pre-European times and O’Malley’s account is accurate enough – but that is where it ends.

O’Malley’s flawed discussion of voting rights is unacceptable in a professional historian. In 1850, full suffrage was only a distant vision of such as the Chartists in Britain, generally regarded as extremists. The first British Reform Act of 1832 had done little more than abolish most “rotten boroughs” and indeed some existing voters were disfranchised by it. A property qualification remained the basis of eligibility to vote. It was only in 1867 that by Disraeli’s “Second Reform Act”, a manoeuvre to outwit his Liberal opponents, a substantial extension of the franchise was made. By then the armed hostilities in the Waikato were over.

With his provocative headline “Grey Area”, O’Malley proceeds to claim that “The ever-wily Grey departed … [in] 1853, ignoring instructions to remain and implement a new constitution that established New Zealand’s Parliament”. Michael King told it differently: “On the whole … his first term … was well executed. The high point may well have been the acceptance by the British Government in 1852 of his new draft constitution … which came into effect the following year, just after he had left the country.” (4)

Following well-established precedents, eligibility to vote required ownership of property valued at £50 a year or leasehold valued at £20. Most settlers failed to qualify while about 100 Maoris who did were accepted without question. It was later realized that as most Maori land was held in common, large numbers were excluded, and so in 1867 the franchise was extended to all Maori men. (5) The franchise for others remained unchanged so that for several years Maori electoral privileges exceeded those of other New Zealanders.

O’Malley asserts that “Maori leaders called in vain for the rights of British subjects promised them in the Treaty of Waitangi.” Since the treaty established exactly equal rights, no less and no more, most settlers had a more legitimate cause for complaint.

O’Malley then proceeds into a realm of fantasy with “By 1861, Grey had returned to the colony. Nearly two years later, after much careful planning and preparation, he invaded the Waikato heartland of the Kingitanga in July 1863, determined to destroy the movement.”

Just for a start, stating that “[Grey] invaded the Waikato heartland” also claimed by many other revisionist authors, is complete nonsense. The Waikato tribal lands were an integral part of the British sovereign territory of New Zealand. Any move to restore effective sovereignty there was entirely legitimate and the armed resistance which was encountered was an overt act of rebellion.

O’Malley’s fantasy continues with “It was a deliberate war of conquest, reliant on a dodgy dossier of evidence” with more in the same vein.

Nevertheless, “heartland”, it was. As Charles Heaphy had observed in 1861, “It is not the natives whose cultivations are interspersed with those of the settlers that have resisted the Queen’s Government and her forces, but chiefly those whose wide and unimproved territories lie most remote from the operations of the colonist.” (6)

Nor was it, as O’Malley’s assertion would indicate, a case of Grey against the Waikato. More than a hundred chiefs at Kohimarama in 1860 had unanimously affirmed their loyalty to the Queen, their Sovereign. (7) As John Robinson relates in his recent book “The Kingite Rebellion”,(8) many other tribes supported the government. Thus: from Rangatira Moetara and six others of Hokianga on 18th June 1861: “O Governor, be strong to strike the fire that is blazing. Strike, extinguish, trample …” and from Tamati Waka Nene and others : “the war is against us all. The Ngapuhi are ready to rise.” “In 1864 … the Arawa people definitely ranged themselves on the side of the Queen as defender of their territory against the rebels.” Nor were all the Waikato on the side of the rebels. Ngati Tipa of Waikato Heads, Ngati Whawhakia of Whangape-Rangiriri, Tainui of the Raglan-Te Aakau area and “a great many of the Ngatihaua” remained loyal – only to be called “Queenites” by the particularly aggressive Ngati Maniopoto.

Neither were Waikato innocent victims of Government aggression. As James Falloon, half-caste native interpreter, later killed by the Hauhaus, reported in June 1863, “The Waikato were to come down in a body to take up a position at Paparata” and proceed to attack from there. Another more ambitious plan was to attack Auckland by night on 1st September 1861. Certain persons were to be saved by a white cross marked on their doors on the night but with this exception, the citizens of Auckland were to be slaughtered. Only the news that Sir George Grey was returning as Governor averted a general rising. (9) Promptly in December Grey travelled to the Waikato in an attempt to defuse the situation. It was not his last attempt.

Since Grey’s terms were simply that the rebels lay down their arms and swear allegiance to the Queen, O’Malley’s: “Spurning Waikato Maori pleas for peace, the governor pushed on after capturing Rangiriri under dubious circumstances in November 1863” is another distorted account.

And so we come to the Rangiaowhia affray about which probably more flagrant lies have been touted than any other event in our history.

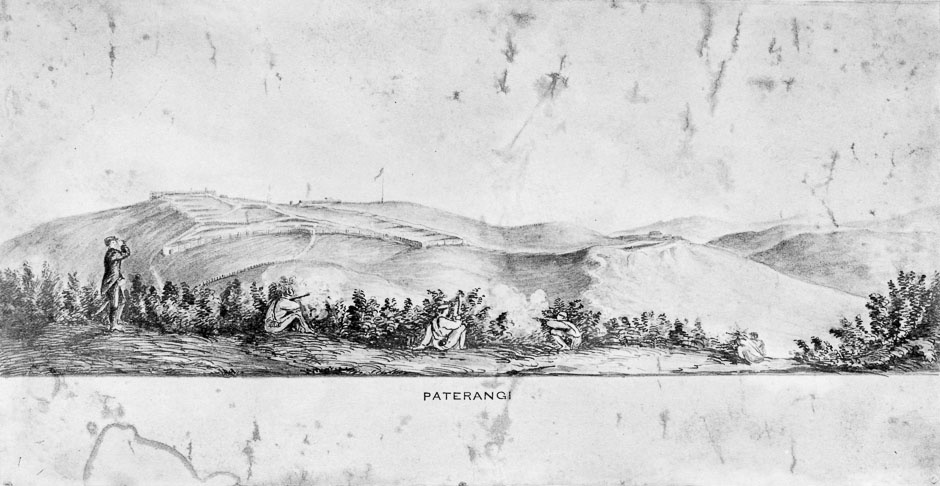

The rebels’ strongly held fort of Paterangi dominated the disputed lands. Contrary to O’Malley’s claim that General Cameron concluded that he could not take it by main force, he decided that an attempt to do so would lead to heavy casualties on both sides which he wished to avoid. As pointed out by long-time military chaplain, Frank Glen “Cameron, with commendable humanitarianism (our emphasis), wanted to avoid a set piece military confrontation because the likely casualties such a battle would engender would be severe on both sides.”

Instead, he decided that a better plan would be to cut off their food supplies. This, of course, is a well-established military tactic. After all, Atlantic U-boats brought Britain uncomfortably close to starvation in 1943. The food source was Rangiaowhia which had become prosperous in the earlier days of peace but now the rules had changed. Cameron decided to occupy the village and destroy its gardens and orchards. Making his move in pre-dawn Sunday darkness to maximise surprise and hence reduce the casualties amongst its occupants. O’Malley describes this as “all the more treacherous” utterly maligning Cameron and ignoring his motives.

The recent rediscovery of consistent accounts of two participants, a member of Cameron’s force and a Maori named Potatau who was a lad at the centre of the action give us now a more accurate picture of the true story than even celebrated historian James Cowan was able to achieve. It is of critical importance that the truth so revealed be told.

To be continued…