Ramesh Thakur

Ramesh Thakur, a Brownstone Institute senior scholar, is a former United Nations Assistant Secretary-General and emeritus professor in the Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) will present two new texts for adoption by its governing body, the World Health Assembly comprising delegates from 194 member states, in Geneva on 27 May–1 June. The new pandemic treaty needs a two-thirds majority for approval and, if and once adopted, will come into effect after 40 ratifications.

The amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR) can be adopted by a simple majority and will be binding on all states unless they recorded reservations by the end of last year. Because they will be changes to an existing agreement that states have already signed, the amendments do not require any follow-up ratification. The WHO describes the IHR as ‘an instrument of international law that is legally-binding’ on its 196 states parties, including the 194 WHO member states, even if they voted against it. Therein lies its promise and its threat.

The new regime will change the WHO from a technical advisory organisation into a supra-national public health authority exercising quasi-legislative and executive powers over states; change the nature of the relationship between citizens, business enterprises, and governments domestically, and also between governments and other governments and the WHO internationally; and shift the locus of medical practice from the doctor-patient consultation in the clinic to public health bureaucrats in capital cities and WHO headquarters in Geneva and its six regional offices.

From net zero to mass immigration and identity politics, the ‘expertocracy’ elite is in alliance with the global technocratic elite against majority national sentiment. The Covid years gave the elites a valuable lesson in how to exercise effective social control and they mean to apply it across all contentious issues.

The changes to global health governance architecture must be understood in this light. It represents the transformation of the national security, administrative, and surveillance state into a globalised biosecurity state. But they are encountering pushback in Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and most recently Ireland. We can but hope that the resistance will spread to rejecting the WHO power grab.

Addressing the World Governments Summit in Dubai on 12 February, WHO Director-General (DG) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus attacked ‘the litany of lies and conspiracy theories’ about the agreement that ‘are utterly, completely, categorically false. The pandemic agreement will not give WHO any power over any state or any individual, for that matter.’ He insisted that critics are ‘either uninformed or lying.’ Could it be instead that, relying on aides, he himself has either not read or not understood the draft? The alternative explanation for his spray at the critics is that he is gaslighting us all.

The Gostin, Klock, and Finch Paper

In the Hastings Center Report “Making the World Safer and Fairer in Pandemics,” published on 23 December, Lawrence Gostin, Kevin Klock, and Alexandra Finch attempt to provide the justification to underpin the proposed new IHR and treaty instruments as ‘transformative normative and financial reforms that could reimagine pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response.’

The three authors decry the voluntary compliance under the existing ‘amorphous and unenforceable’ IHR regulations as ‘a critical shortcoming.’ And they concede that ‘While advocates have pressed for health-related human rights to be included in the pandemic agreement, the current draft does not do so.’ Directly contradicting the DG’s denial as quoted above, they describe the new treaty as ‘legally binding’. This is repeated several pages later:

…the best way to contain transnational outbreaks is through international cooperation, led multilaterally through the WHO. That may require all states to forgo some level of sovereignty in exchange for enhanced safety and fairness.

What gives their analysis significance is that, as explained in the paper itself, Gostin is ‘actively involved in WHO processes for a pandemic agreement and IHR reform’ as the director of the WHO Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law and a member of the WHO Review Committee on IHR amendments.

The WHO as the World’s Guidance and Coordinating Authority

The IHR amendments will expand the situations that constitute a public health emergency, grant the WHO additional emergency powers, and extend state duties to build ‘core capacities’ of surveillance to detect, assess, notify, and report events that could constitute an emergency.

Under the new accords, the WHO would function as the guidance and coordinating authority for the world. The DG will become more powerful than the UN Secretary-General. The existing language of ‘should’ is replaced in many places by the imperative ‘shall,’ of non-binding recommendations with countries will ‘undertake to follow’ the guidance. And ‘full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons’ will be changed to principles of ‘equity’ and ‘inclusivity’ with different requirements for rich and poor countries, bleeding financial resources and pharmaceutical products from industrialised to developing countries.

The WHO is first of all an international bureaucracy and only secondly a collective body of medical and health experts. Its Covid performance was not among its finest. Its credibility was badly damaged by tardiness in raising the alarm; by its acceptance and then rejection of China’s claim that there was no risk of human-human transmission; by the failure to hold China accountable for destroying evidence of the pandemic’s origins; by the initial investigation that whitewashed the origins of the virus; by flip-flops on masks and lockdowns; by ignoring the counterexample of Sweden that rejected lockdowns with no worse health outcomes and far better economic, social, and educational outcomes; and by the failure to stand up for children’s developmental, educational, social, and mental health rights and welfare.

With a funding model where 87 percent of the budget comes from voluntary contributions from the rich countries and private donors like the Gates Foundation, and 77 percent is for activities specified by them, the WHO has effectively ‘become a system of global public health patronage’, write Ben and Molly Kingsley of the UK children’s rights campaign group UsForThem. Human Rights Watch says the process has been ‘disproportionately guided by corporate demands and the policy positions of high-income governments seeking to protect the power of private actors in health including the pharmaceutical industry.’ The victims of this catch-22 lack of accountability will be the peoples of the world.

Much of the new surveillance network in a model divided into pre-, in, and post-pandemic periods will be provided by private and corporate interests that will profit from the mass testing and pharmaceutical interventions. According to Forbes, the net worth of Bill Gates jumped by one-third from $96.5 billion in 2019 to $129 billion in 2022: philanthropy can be profitable. Article 15.2 of the draft pandemic treaty requires states to set up ‘no fault vaccine-injury compensation schemes,’ conferring immunity on Big Pharma against liability, thereby codifying the privatisation of profits and the socialisation of risks.

The changes would confer extraordinary new powers on the WHO’s DG and regional directors and mandate governments to implement their recommendations. This will result in a major expansion of the international health bureaucracy under the WHO, for example new implementation and compliance committees; shift the centre of gravity from the common deadliest diseases (discussed below) to relatively rare pandemic outbreaks (five including Covid in the last 120 years); and give the WHO authority to direct resources (money, pharmaceutical products, intellectual property rights) to itself and to other governments in breach of sovereign and copyright rights.

Considering the impact of the amendments on national decision-making and mortgaging future generations to internationally determined spending obligations, this calls for an indefinite pause in the process until parliaments have done due diligence and debated the potentially far-reaching obligations.

Yet disappointingly, relatively few countries have expressed reservations and few parliamentarians seem at all interested. We may pay a high price for the rise of careerist politicians whose primary interest is self-advancement, ministers who ask bureaucrats to draft replies to constituents expressing concern that they often sign without reading either the original letter or the reply in their name, and officials who disdain the constraints of democratic decision-making and accountability. Ministers relying on technical advice from staffers when officials are engaged in a silent coup against elected representatives give power without responsibility to bureaucrats while relegating ministers to being in office but not in power, with political accountability sans authority.

US President Donald Trump and Australian and UK Prime Ministers Scott Morrison and Boris Johnson were representative of national leaders who had lacked the science literacy, intellectual heft, moral clarity, and courage of conviction to stand up to their technocrats. It was a period of Yes, Prime Minister on steroids, with Sir Humphrey Appleby winning most of the guerrilla campaign waged by the permanent civil service against the transient and clueless Prime Minister Jim Hacker.

At least some Australian, American, British, and European politicians have recently expressed concern at the WHO-centred ‘command and control’ model of a public health system, and the public spending and redistributive implications of the two proposed international instruments. US Representatives Chris Smith (R-NJ) and Brad Wenstrup (R-OH) warned on 5 February that ‘far too little scrutiny has been given, far too few questions asked as to what this legally binding agreement or treaty means to health policy in the United States and elsewhere.’

Like Smith and Wenstrup, the most common criticism levelled has been that this represents a power grab at the cost of national sovereignty. Speaking in parliament in November, Australia’s Liberal Senator Alex Antic dubbed the effort a ‘WHO d’etat’.

A more accurate reading may be that it represents collusion between the WHO and the richest countries, home to the biggest pharmaceutical companies, to dilute accountability for decisions, taken in the name of public health, that profit a narrow elite. The changes will lock in the seamless rule of the technocratic-managerial elite at both the national and the international levels. Yet the WHO edicts, although legally binding in theory, will be unenforceable against the most powerful countries in practice.

Moreover, the new regime aims to eliminate transparency and critical scrutiny by criminalising any opinion that questions the official narrative from the WHO and governments, thereby elevating them to the status of dogma. The pandemic treaty calls for governments to tackle the ‘infodemics’ of false information, misinformation, disinformation, and even ‘too much information’ (Article 1c). This is censorship. Authorities have no right to be shielded from critical questioning of official information. Freedom of information is a cornerstone of an open and resilient society and a key means to hold authorities to public scrutiny and accountability.

The changes are an effort to entrench and institutionalise the model of political, social, and messaging control trialled with great success during Covid. The foundational document of the international human rights regime is the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Pandemic management during Covid and in future emergencies threaten some of its core provisions regarding privacy, freedom of opinion and expression, and rights to work, education, peaceful assembly, and association.

Worst of all, they will create a perverse incentive: the rise of an international bureaucracy whose defining purpose, existence, powers, and budgets will depend on more frequent declarations of actual or anticipated pandemic outbreaks.

It is a basic axiom of politics that power that can be abused, will be abused – some day, somewhere, by someone. The corollary holds that power once seized is seldom surrendered back voluntarily to the people. Lockdowns, mask and vaccine mandates, travel restrictions, and all the other shenanigans and theatre of the Covid era will likely be repeated on whim. Professor Angus Dalgliesh of London’s St George’s Medical School warns that the WHO ‘wants to inflict this incompetence on us all over again but this time be in total control.’

Covid in the Context of Africa’s Disease Burden

In the Hastings Center report referred to earlier, Gostin, Klock, and Finch claim that ‘lower-income countries experienced larger losses and longer-lasting economic setbacks.’ This is a casual elision that shifts the blame for harmful downstream effects away from lockdowns in the futile quest to eradicate the virus, to the virus itself. The chief damage to developing countries was caused by the worldwide shutdown of social life and economic activities and the drastic reduction in international trade.

The discreet elision aroused my curiosity on the authors’ affiliations. It came as no surprise to read that they lead the O’Neill Institute – Foundation for the National Institutes of Health project on an international instrument for pandemic prevention and preparedness.

Gostin et al grounded the urgency for the new accords in the claim that ‘Zoonotic pathogens…are occurring with increasing frequency, enhancing the risk of new pandemics’ and cite research to suggest a threefold increase in ‘extreme pandemics’ over the next decade. In a report entitled “Rational Policy Over Panic,” published by Leeds University in February, a team that included our own David Bell subjected claims of increasing pandemic frequency and disease burden behind the drive to adopt the new treaty and amend the existing IHR to critical scrutiny.

Specifically, they examined and found wanting a number of assumptions and several references in eight G20, World Bank, and WHO policy documents. On the one hand, the reported increase in natural outbreaks is best explained by technologically more sophisticated diagnostic testing equipment, while the disease burden has been effectively reduced with improved surveillance, response mechanisms, and other public health interventions. Consequently there is no real urgency to rush into the new accords. Instead, governments should take all the time they need to situate pandemic risk in the wider healthcare context and formulate policy tailored to the more accurate risk and interventions matrix.

The lockdowns were responsible for reversals of decades worth of gains in critical childhood immunisations. UNICEF and WHO estimate that 7.6 million African children under five missed out on vaccination in 2021 and another 11 million were under-immunised, ‘making up over 40 per cent of the under-immunised and missed children globally.’ How many quality adjusted life years does that add up to, I wonder? But don’t hold your breath that anyone will be held accountable for crimes against African children.

Earlier this month the Pan-African Epidemic and Pandemic Working Group argued that lockdowns were a ‘class-based and unscientific instrument.’ It accused the WHO of trying to reintroduce ‘classical Western colonialism through the backdoor’ in the form of the new pandemic treaty and the IHR amendments. Medical knowledge and innovations do not come solely from Western capitals and Geneva, but from people and groups who have captured the WHO agenda.

Lockdowns had caused significant harm to low-income countries, the group said, yet the WHO wanted legal authority to compel member states to comply with its advice in future pandemics, including with respect to vaccine passports and border closures. Instead of bowing to ‘health imperialism,’ it would be preferable for African countries to set their own priorities in alleviating the disease burden of their major killer diseases like cholera, malaria, and yellow fever.

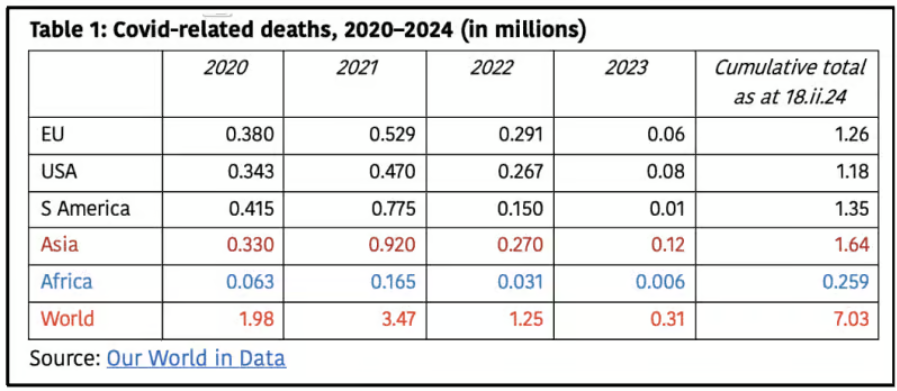

Europe and the US, comprising a little under 10 and over four per cent of world population, account for nearly 18 and 17 per cent, respectively, of all Covid-related deaths in the world. By contrast Asia, with nearly 60 per cent of the world’s people, accounts for 23 percent of all Covid-related deaths. Meantime Africa, with more than 17 per cent of global population, has recorded less than four per cent of global Covid deaths (Table 1).

According to a report on the continent’s disease burden published last year by the WHO Regional Office for Africa, Africa’s leading causes of death in 2021 were malaria (593,000 deaths), tuberculosis (501,000), and HIV/AIDS (420,000). The report does not provide the numbers for diarrhoeal deaths for Africa. There are 1.6 million such deaths globally per year, including 440,000 children under five. And we know that most diarrhoeal deaths occur in Africa and South Asia.

If we perform a linear extrapolation of 2021 deaths to estimate ballpark figures for the three years 2020–22 inclusive for numbers of Africans killed by these big three, approximately 1.78 million died from malaria, 1.5 million from TB, and 1.26 million from HIV/AIDS. (I exclude 2023 as Covid had faded by then, as can be seen in Table 1.) By comparison, the total number of Covid-related deaths across Africa in the three years was 259,000.

Whether or not the WHO is pursuing a policy of health colonialism, therefore, the Pan-African Epidemic and Pandemic Working Group has a point regarding the grossly exaggerated threat of Covid in the total picture of Africa’s disease burden.

A shorter version of this was published in The Australian on 11 March.