Philip Temple

Victoria University of Wellington – Te Herenga Waka

democracyproject.nz

Dr Philip Temple ONZM has been writing and commentating on current affairs for decades. He was given a Wallace Award by the Electoral Commission for the quality of his writing on the electoral system.

On 24 April the Minister for Maori Development, the Hon. Willie Jackson, stated on TVNZ’s Q+A programme that government plans for Maori co-governance were part of MMP. It meant ‘shared decision-making’, ‘partnership’, ‘diversity, about minorities working together’. ‘Co-governance is based on the principles of MMP, this is a consensus type democracy now’, ‘not the tyranny of the majority anymore’. And ‘co-governance and co-partnership are the same thing’ as MMP.

In 1992 and 1993, a dual referendum process was undertaken before MMP was voted on to change our electoral system. The electoral information process was overseen by the neutral non-partisan Electoral Referendum Panel. All this was based on the exhaustive 1986 Report of the Royal Commission on the Electoral System, ‘Towards a Better Democracy’. By the time the MMP vote was taken in November 1993, the issues has been throughly aired and debated, encouraged by organisations such as the Electoral Reform Coalition (for) and the Campaign for Better Government (against).

Among the arguments for MMP were that this proportional system would give better, balanced representation in Parliament for women, Maori and diverse ethnicities. This has happened, so that currently about 48% of members are women, 20% are Maori and Parliament also has members from the Pasifika, African, Latin American, Indian, Sri Lankan and Chinese communities. There are five parties represented in Parliament, including Te Paati Maori which benefits from the provision of separate seats for Maori and the one-electorate rule. Improvements can be made to our flexible MMP system, but both Labour and National governments have avoided doing so.

Co-governance has already been achieved, where virtually every sector of our community is represented and has a direct say in Parliament and government. Of the 20 members of Cabinet, there are eight women, including our prime minister; six are Maori, two Pasifika and one of Sri Lankan descent. Outside of Parliament, we have a Maori governor-general, a woman chief justice as one of three women on the panel of six, including a Maori justice, making up the Supreme Court. There is also the Waitangi Tribunal representing Maori interests and whose recommendations to government most often make their way into law.

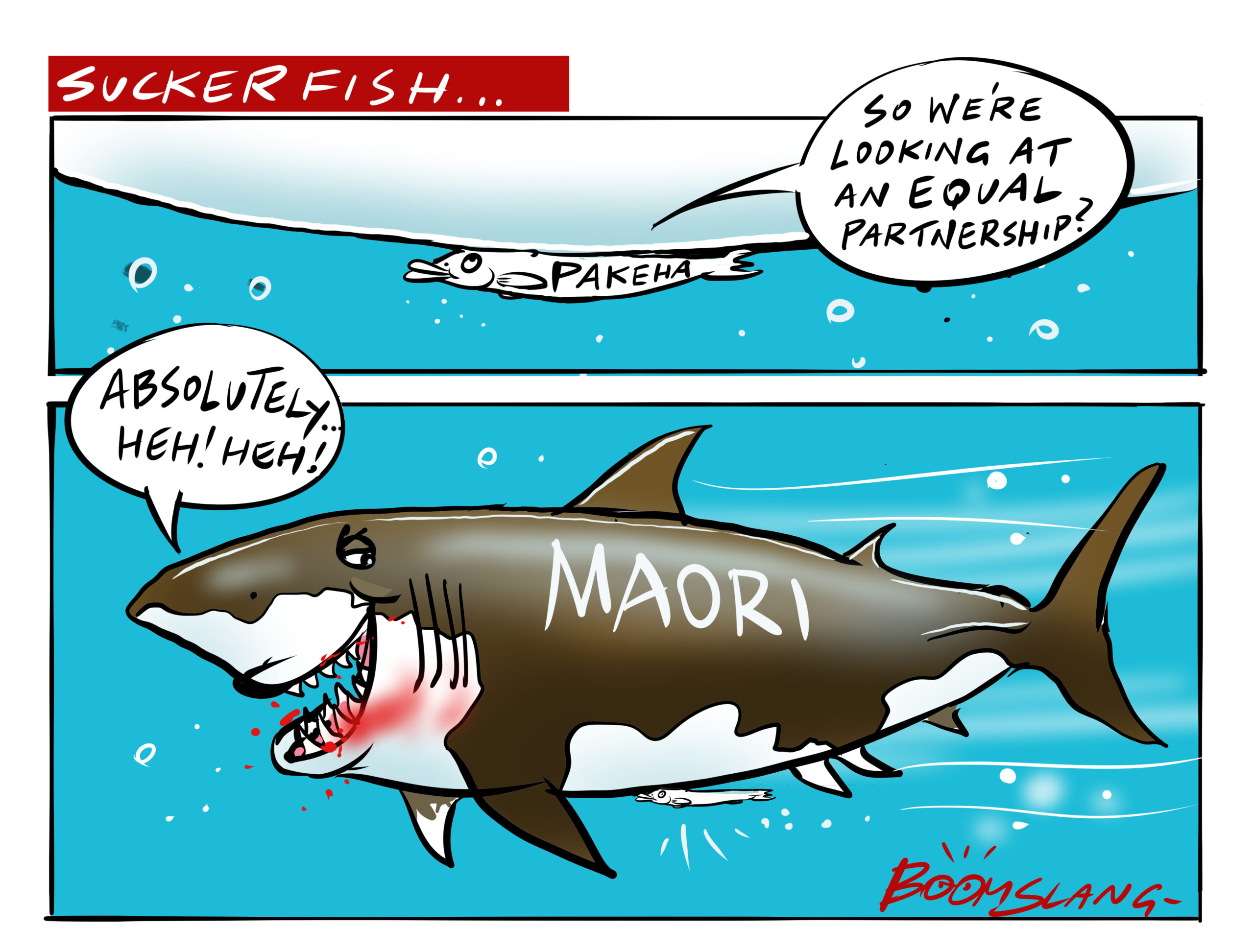

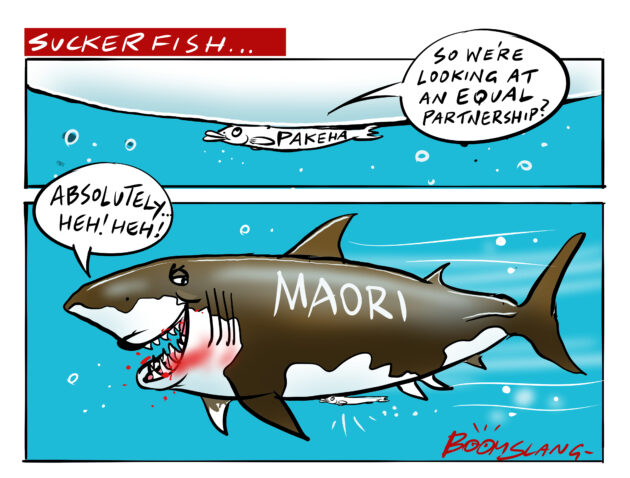

So if we already have co-governance through MMP, what is Willie Jackson and his Maori caucus really seeking to achieve?

In his Q+A interview, he repeated the familiar arguments about Maori being on the downside of all the statistics relating to health, education, crime, ‘everything except skin cancer’ and that more co-governance at the higher levels of government would bring about the ‘equity’ that was promised in Article Three of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Maori social ills are indeed bad and need fixing, but equity in Article Three of the Treaty refers to everyone in this country, not just Maori. Fifty per cent of people in prison are Maori but that means fifty per cent are non-Maori. Maori have life expectancies about seven years less than Pakeha (but the gap is narrowing), and this is about five years less than people in the Asian community. Statistics can be used to argue anything. But equity means equity for all and the main drivers of inequity are poor health, poor education, and an international neoliberal economic system that works off low-wage economies and mostly rewards the top 5% of people in any country, regardless of ethnicity (and this includes Mr Jackson). This is where the change needs to take place.

Willie Jackson said ‘democracy has changed’ and we are no longer operating under a First Past the Post electoral system. Yet this current government, with its rare absolute majority, is exhibiting the worst aspects of it by pushing forward with electoral and constitutional change without an electoral mandate or widespread debate within all sectors of the community.

Supporters of the change continually fall back on the shibboleth that the Treaty mandates equity and partnership for Maori (or whatever argument currently serves) and is a ‘living document’. If it is, then the other partner or partners, representing more than 80% of the population, also deserve – indeed must have – an equal opportunity to discuss and decide what the Treaty and its qualities mean today. Ad hoc decisions by a government of the day are not acceptable.

Willie Jackson repeatedly said that non-Maori had ‘nothing to fear’ from co-governance, even if this meant Maori held 50% of decision-making on such nationally important bodies as the proposed Three Waters governance structures. Apparently, equity does not matter in these cases. There is a great deal to fear in such a seminal shift away from the basic principles of democracy. And it is unlikely to stop there.

But let’s all talk about it. Let there be a national discussion about the Treaty and its evolving ‘principles’ under the auspices of a neutral body such as a Royal Commission. What does it mean now, this document put together 182 years ago by a few people in a few days, in isolation, and in a time when cultures, politics, economics and technologies were vastly different? Old treaties, such as Magna Carta, are the basis for later ones, new laws and developments. Let us sit down and create a new ‘treaty,’ one that we can all celebrate and move forward with. Then we will truly have ‘nothing to fear’ and we might be surprised at what we come up with.

This article can be republished under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Attributions should include a link to the Democracy Project.