It seems that every Australian and New Zealand family whose roots in their lands reach back at least to the 1900s has an ANZAC story. This is mine.

Jack was born in the 1870s in Tasmania. Jack’s parents were both free settlers (an important distinction in Colonial Tasmania), his father from Holland, his mother from Scotland. Throughout his childhood, the family moved around Northern Tasmania, before settling in Launceston, where his father was a Master Mariner.

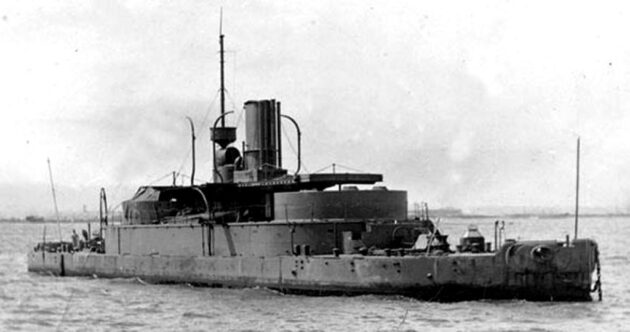

In the 1900s, Jack migrated across Bass Strait and settled in Port Melbourne, where he would spend most of the rest of his life. Perhaps carrying on a family seafaring tradition, Jack joined the newly-established Royal Australian Naval Reserves. As a reservist, he would have served on the HMAS Cerberus, at one time “the last word in naval architecture” and the most powerful vessel in the southern hemisphere. But, by the eve of WWI, the ship’s weapons and boilers were inoperable.

With the outbreak of war, Jack tried to enlist in the Navy, but was rejected on account of his false teeth. “I don’t want to bite the bastards”, he retorted. So, instead he joined the Army. The only hurdle there was his age: at 40, Jack was well beyond the cut-off age of 35 for the First AIF. In a war where many young men lied that they were older in order to join up, Jack instead lied that he was younger.

In October 1914, Jack embarked with the rest of the 5th Battalion on the HMAT Orvieto. After stopping at Albany, the Orvieto led the convoy of 36 transports and the battleship Sydney, bound for Egypt. The men aboard the Orvieto saw their first Germans a few weeks later, when the ship took aboard the survivors of the German raider Emden, sunk by the Sydney at the Battle of Cocos.

In December, the convoy landed at Alexandria. But instead of continuing on to the “real war” in France, as they had expected, Jack and his mates were readied for their first action in what seemed at that time a sideshow: the Dardanelles campaign, which would lay the foundations of the ANZAC legend.

As it happened, Jack missed going in with the second wave of the landing on that infamous April 25th, 1915. Due to a minor indiscretion, he was spending a week in the brig. Still, Jack apparently distinguished himself: after rejoining his battalion, he was quickly promoted to corporal. Months later, at the Battle of Lone Pine, he was wounded for the first time.

When the Dardanelles campaign finally ground to a halt and the ANZACS were withdrawn, Jack’s battalion returned to Egypt where an unpleasant shock awaited them. With the arrival of a second convoy of new recruits, and the First AIF suffering heavy losses at Gallipoli, it was decided to split the existing battalions as well as create new ones, integrating the fresh recruits with the veterans. So Jack left the 5th, with whom he had fought for so many months, and joined the newly-formed 57th Battalion.

For the next few months the AIF resumed training in the desert sands, and Jack was promoted to sergeant and sent to machine-gun school. Then the AIF was finally sent off to France. After a brief stopover in Marseilles, where, 90 years later, surviving battalion members still fondly recalled the Mediterranean city – its wine, especially – they travelled north, to the Belgian border, and a little town called Fromelles.

By this time the Battle of the Somme had been raging for three weeks, 80 kilometres to the south. The attack at Fromelles was designed to exploit a weakened German front line at Fromelles, many of its infantry having been transferred to defend the Somme. Fromelles was the first major battle fought by Australian troops on the Western Front – and is remembered as “the worst 24 hours in Australia’s entire history”.

The only high ground on the battlefield was the German salient called the Sugarloaf. From there, German guns and machine-gunners overlooked the no man’s land on both flanks. The weather was also poor: heavy rain postponed the planned attack by a day.

In fact, the weather almost certainly saved Jack’s life. His 57th battalion was scheduled to go over in the first wave of the attack. But, with the attack postponed, the 57th was rotated out of the front line and replaced by the 53rd.

The next day, the 53rd led the attack. Three-quarters of the battalion were killed or wounded, including its commanding officer, mortally wounded by shellfire.

Even before the battle itself, another member of the 57th wrote that “we were in Hell, bombardments of high explosives and shrapnel from both sides every day, but two nights, in particular, were ‘horries’.” Those “horries” were the nights following the slaughter of the 53rd, when the men of the 57th made it their mission to venture into no man’s land, searching for and rescuing survivors.

“I must say Fritz treated us very fairly, though a few were shot at the work,” wrote another sergeant of the 57th, Sgt Simon Fraser. “Some of these wounded were game as lions and got rather roughly handled, but haste was more necessary than gentle handling and we must have brought in over 250 men by our company alone.”

In the mud and fog of the battlefield, men of the 57th laboured to bring in the wounded. The call of a wounded man in no man’s land “was an appeal no man could stand against”. As one crew of volunteers with stretchers were bringing in a wounded man, they heard a voice sing out about 30 yards away, “Don’t forget me, cobber”. That moment is immortalised in the “cobbers” monument, the ANZAC’s memorial at Fromelles.

Little did Jack and his mates know that, somewhere across the mud of no man’s land, sheltering in a concrete bunker, was a German corporal who would return to the battlefield a quarter-century later as the triumphant conqueror of France and the Fuhrer of the German Reich.

After Fromelles, Jack remained with the 57th at the Somme. Although they weren’t engaged in any major battles during this time, battalion diaries record constant trench raids and German shelling. It was during one night of particularly intense shelling that Jack received his second wound, hit in the knee by shell fragments. He went to recover in Britain, then in October 1917, he was invalided home to Australia.

Back in Port Melbourne, he married a local girl and settled there for the rest of his life. Through the 20s and the Depression years, he raised four children and worked at the Port Melbourne docks, including through the infamous 1928 strike.

But, if he had left the War behind in 1917, the War never left him. “Dad never talked about the War”, as so many children of that generation remembered, but the War was always there. The psychological scars, of course, and the splinters of metal in his knee, which would eventually cripple him, after a fall from a ladder. Always a practical man, a doer, once Jack was bedridden at the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital, the end wasn’t far away. Jack died in 1948.

So many Australian and New Zealand families have their ANZAC stories. This was one of them.