Kieran Madden

maxim.org.nz

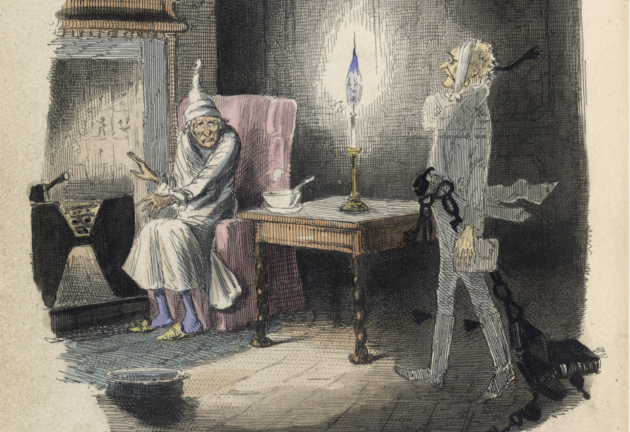

Prime Minister Ardern is sitting on a shiny mountain of political capital that would, as one editorial pointed out, make Disney’s Scrooge McDuck jealous. The problem for Ardern and her Government is that those arguing for a big spend to tackle child poverty are getting impatient. In their eyes, Ardern is more like Dickens’ Ebeneezer Scrooge.

Marley’s Ghost – A Christmas Carol (1843)

Post-election hope was met with disappointment. More than 60 charitable organisations—from Salvation Army to Barnados, food banks to housing providers—wrote an open letter to Ardern and her Ministers of Finance and Social Development asking them to raise benefits before Christmas. “Before the election, the Labour party has consistently said there’s more work to be done to lift families out of poverty,” the letter said, “you now have the mandate and opportunity to do so.”

Ardern’s response? A firm no. She also said “this is not going to be an issue that can be resolved in one week, or one month or indeed one term.” But what is she waiting for? Some groups called her response “disconnected,” that it “reeks of privilege,” and yet another that the Government should “ashamed of the blatant lack of compassion and action for those doing it the hardest.”

Ardern’s response? A firm no.

This is all made more poignant by the fact that Ardern chose to retain her role as Minister for Child Poverty Reduction, the issue that she said got her into politics in the first place. Here, success is laid out in the Child Poverty Reduction Act that the Labour-led Government passed in 2018 that outlines three and 10 year targets.

Meeting the 2028 targets requires more than tinkering at the edges. Crucially, the way the income measures have been devised, the only way to meet them is a considerable spend on core benefits. The Government’s Advisory Group suggested raising benefits by as much as 47%, an extra $5.2 billion every year. For context, $13 billion was spent on wage subsidies this year.

This captures the reality of poverty—that it is about more than income

Treasury modelling suggests that several of the income-based measures are close to meeting the 2021 targets, however the material hardship measures (things like regular meals, clothing, and housing) have barely moved, and only expected to get worse as a result of COVID-19. This captures the reality of poverty—that it is about more than income, and even if the Government goes big on redistribution, hardship will likely still remain. This is why multiple measures, and holistic responses, are important.

With Winston Peters and New Zealand First no longer there to “bah, humbug” Labour’s progressive policies, Cabinet can no longer blame recalcitrant coalition partners. Complicating matters, Ardern took revenue-raising policies off the table, ruling out both a capital gains tax and a wealth tax—not just for this term but for as long as she is Prime Minister. So this basically leaves more borrowing and debt.

Child Poverty will be an election-defining, touchstone issue this term. Ambitious targets will need ambitious policies. If the gap between the Governments’ talk on this issue and their actions continues, they will be eaten up by a political chasm of their own making.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.