OPINION

Al Johnson

A few days ago a letter to the Chair of the UK Covid inquiry (led by Great Barrington Declaration author, Sunetra Gupta, of the University of Oxford) relayed their concerns on what they saw as biases in the inquiry and that key assumptions were being taken for granted “…instead of examining and critiquing them in light of the evidence.” They also requested to see a broader range of scientific experts with more critical viewpoints.

The New Zealand Royal Commission of Inquiry into COVID-19 Lessons Learned already has the (deserved) perception that it suffers from the same issues. But the change in government has at least led to public submissions on what the terms of reference should be for the Inquiry.

The current scope does include ‘modelling and surveillance systems’ but doesn’t seem to explicitly review the basis on which decisions were made (in which modelling was a key factor) nor how the outcomes of those decisions were analysed and measured. This includes how and when government sought or considered critical viewpoints to ensure robust decision-making.

Only days into the 1st lockdown in early April 2020, the Otago University academics who did the initial modelling and then produced the report that recommended elimination, Michael Baker and Nick Wilson, had a self-congratulatory opinion piece published in The Guardian. They mostly used it to claim success for their just-implemented ideas, which they boasted was a world first, and nauseatingly called then Prime Minster Jacinda Ardern’s leadership “brilliant, decisive and humane”.

Further down their piece, they include a sentence where they admit the lockdown does “…have massive short-term social and economic costs” that would be most felt by low-income New Zealanders.

Baker and Wilson co-authored a quick attempt at an almost/sort-of cost-benefit analysis (a CBA) at the bottom of a blog post. Spoiler: it confirmed their beliefs. But notably the co-author on the post was their frequent collaborator, the current Commissioner on the Covid Inquiry in New Zealand – Tony Blakely – who is their former colleague from Otago University!

But largely there wasn’t much, if any, serious analysis on the consequences of these decisions before they were made.

The costs and impacts of lockdown decisions

While the Productivity Commission has now been disestablished, in 2020 they wrote a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) on 20 April 2020 decision to extend New Zealand’s initial lockdown further.

Their CBA was sparked by the fact the decision was announced as being based on what sounded like a CBA of sorts as the extension was claimed to deliver “much greater long-term health and economic returns”.

I haven’t seen any proactively released document that explicitly quantified or analysed those said returns – which was the same finding of the CBA author at the time.

There was limited discussion of the lockdown’s impacts within official documents. A Cabinet paper titled “Preparing to review New Zealand’s Level 4 Status” from 14 April 2020 said it may be several years before economic activity returns to pre-Covid levels and there was some Treasury modelling showing “…enormous negative effects on economic activity that get worse the longer the restrictions last”. It noted that the impact would be most felt by smaller businesses and “…people on lower incomes or with low savings”.

The paper also mused “…social impacts of the lockdown are also likely to be significant” and there could be sharp increases in family violence rates.

The follow-up Cabinet paper from 20 April 2020 which recommended the lockdown extension confirmed that a “significant increase” had been seen in police callouts for family violence during the lockdown. It also spelt out that the health system was not under any strain. The imposition of a lockdown meant any non-urgent medical care was postponed and public hospitals were only operating at 50 to 60 per cent of their capacity during lockdown, with over 70,000 appointments outright cancelled or deferred.

This paper that largely recommended extending the lockdown surprisingly talks more about some of the impacts that were becoming apparent, and makes no mention of any potential ‘returns’ from the extension – other than stating that while community transmission was now ‘unlikely’, everyone needed to be eased into the little bit less of a lockdown that constituted Level 3! However, accompanying the paper was obedient modelling to support this extension by the only modeller now used by the government – Shaun Hendy from his research think tank, Te Pünaha Matatini (TPM), hosted by the University of Auckland.

The Productivity Commission’s cost-benefit analysis of this 5-day extension of Level 4 was that it cost the economy an estimated $741 million. Hendy disagreed with their estimation and publicly demanded the Commission retract the paper; the Commission stood by their analysis and eventually stopped engaging with him when he attacked them over X (Twitter).

The appendix of that CBA included the apt mention that the author’s colleagues and the media appeared supportive of both the lockdown and the extension – but all those people were able to work during the lockdown. Lockdowns are seen by many people and ‘experts’ in other countries now as a class-based response with no evidence to support their use at the time they were enacted. While there has been little to no explicit mainstream discussion of this in New Zealand, economists were considering their impacts.

Further CBAs cropped up outside of government, including by former academic Martin Lally, economist Ian Harrison (who also critiqued the Otago University modelling) and academic John Gibson. He commented, “…poorer people and poorer societies have lower life expectancy. The actions being taken to deal with the Covid-19 risk are making New Zealand poorer, and so will reduce life expectancy.”

However, The Department of Prime Minister and the Cabinet (DPMC) confirmed in a 2022 OIA response they never considered Gibson’s cost-benefit analysis in particular – but nor did they perform or commission at any time any quantitative analysis when considering the impact of lockdowns on the public’s health and well being.

Let that sink in.

Once the elimination approach was adopted, no discussion of it, and hence no analysis, could be entertained. Pursuing an objective without considering the costs? How can robust decisions ever be made if they cannot withstand critique?

Martin Kulldorff in an interview with Jay Bhattacharya observed that when they released the Great Barrington Declaration with Sunetra Gupta it clearly exposed there was no universal scientific consensus on what had become the de-facto pandemic policy across many countries.

There was in fact a debate among scientists on the efficacy versus the impacts of these restrictive measures – but it was being actively suppressed from view.

Differing views censored to maintain the ‘illusion of consensus’

Prior to the lockdown’s extension, an epidemiologist from the University of Auckland, Simon Thornley, alongside other academics called for something similar to the Great Barrington Declaration in New Zealand to allow normal life to resume. (I think it’s important to remember that New Zealand’s Level 4 lockdown was stricter than in most countries, and the step down, Level 3, still meant schools, workplaces and retail could not fully re-open.)

Thornley was given some airtime by some media near the start of the lockdown in April 2020.

But this article shows the play book that quickly gathered steam. His views were torn down through commentary from government-endorsed experts Michael Baker and ‘30 interviews a day’ Siouxsie Wiles. Yet it’s blatantly obvious that their statements that disagree with Thornley are not treated with the same scrutiny or questioning. The article spiralled to end with Wiles alleging Thornley – unlike herself, presumably – just didn’t care as much about people to be questioning the lockdown.

By the time the vaccine rollout slowly started in early 2021, any alternative viewpoint was treated with open derision or suppressed from view. By May 2021 the media were actively attacking Thornley with everything they had: “The scientist and the rabbit hole: How epidemiologist Simon Thornley became an outcast of his profession”. The same year NZ Skeptics awarded him their ‘bent spoon’ award for what they called his lack of critical thinking, along with his having the gall to oppose lockdowns and sign the Great Barrington Declaration.

The 14 April 2020 Cabinet paper that considered how to move on from a full lockdown also mentioned, “The real issue is social acceptance. Variation could, if not well managed, cut away at the ‘we are all in this together’ narrative. There would need to be compelling, widely accepted evidence…without that, public support may be harder to secure and maintain.”

The messaging of Covid restrictions was relentless to convince people to follow this policy by stoking an underlying fear of Covid. Hundreds of millions were spent buying airtime to run Covid messaging constantly, and propping up journalism (the public interest journalism fund was also used to fund media stories against what was labelled Covid misinformation).

The Inquiry’s terms also find the need to mention, “The measures New Zealand put in place to respond to COVID-19 generally enjoyed high levels of public support, and were positively reviewed by independent experts.” But these measures were massaged and manipulated using flashy advertising agencies and heavy doses of behavioural nudging to increase acceptance of them. Catastrophising Covid conveniently became the ultimate click-bait for media (and a good guys vs bad guys narrative is even better), which was often to the detriment of asking basic and relevant questions. All of which combined led to what appears to be the political capture of science.

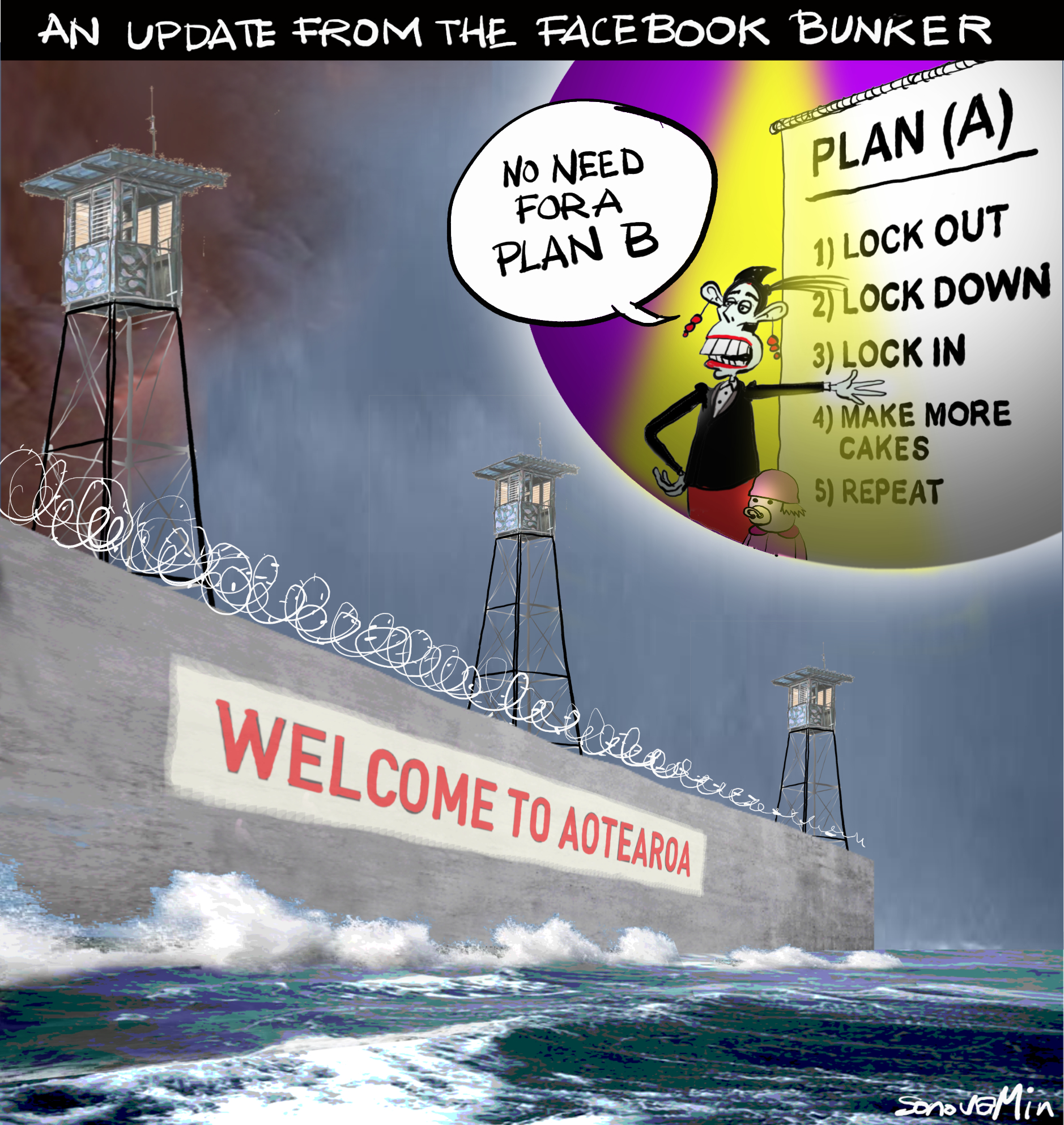

Differing views or critical scrutiny were stamped out of the policy response, as it would destroy the illusion the government had spun of being a supremely rational but benign cross-societal force.

The premise of the current Covid Inquiry is to prepare for the next pandemic which on the face of it appears very similar to the UK’s inquiry. It’s institutionalising aspects of the Covid response without adequately questioning or reviewing vast parts of it.

Public submissions on the terms of reference close on March 24th.