Chris Penk

First published by The BFD 21th June 2020

The BFD is serialising National MP Chris Penk’s book Flattening the country by publishing an extract every day.

Disconcerting developments

It is worth remembering throughout all of this that the unbelievably cavalier attitude of the government right up to (and including) mid-March had got our country into this mess in the first instance.

It seems so long ago now – but, importantly, it was only shortly prior to the Alert Level 4 lockdown – that the infamous episode of the Tool concert moshpit took place.

Newshub told the story well:

On Friday, Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield revealed one of New Zealand’s four confirmed patients attended the legendary metal band’s show at Auckland’s Spark Arena on February 28.

He was in the general admission standing area near the front – close to, if not in, the moshpit.

But Dr Bloomfield said the chance of the deadly disease being passed on to others was low.

His description of a moshpit as ‘casual’ rather than ‘close contact’ however bemused rock fans, who know moshpits can be a heaving mess of sweat, saliva and in some cases, even blood.

It may surprise readers now to recall that back in March everything was fair game: moshpits, sandpits and pulpits, all of which were outright banned shortly thereafter for many weeks.

It almost goes without saying that the Health Minister didn’t bother to ask officials any obvious questions about this anomaly himself. And nor did he take a hint when a journalist (as reported in the same story) asked him:

You’ve got to remember this disease spreads by coughing, by big droplets – you’ve actually got to be very close to somebody for an extended period of time.”

Shepherd pointed out being in a Tool moshpit for two hours might fit that definition, but Dr Clark dismissed his concerns.

And then again when the National Party’s health spokesperson, Michael Woodhouse prosecuted the case similarly in Question Time, in Parliament on 12 March 2020:

Woodhouse:

Does he stand by his answer in oral question 10 yesterday regarding those in the mosh pit at the Tool concert on 28 February that “Those people who were in that situation have been identified as casual contacts”?

Clark:

Yes, because that is the advice of the public health experts—the doctors and scientists who understand the science of communicable disease transmission.

Woodhouse:

What is the definition of a “close contact”?

Clark:

A close contact is someone who is within about a metre and a half, for more than 15 minutes.

Woodhouse:

Given that answer, does he really believe patrons in the mosh pit and close to the affected patron were considered “casual contacts”, given the concert lasted several hours?

Clark:

I’m not going to second-guess the clinical judgment of scientific experts.

Woodhouse:

Has he ever been in a mosh pit?

And then the absolute killer:

Woodhouse:

What advice would he give to people considering attending events like the Pasifika Festival or the Christchurch memorial this weekend in light of the COVID-19 outbreak?

Clark:

No one in the world can give any absolute guarantees in the current environment, but I can remind the member that we’ve only had five confirmed cases of COVID-19 in New Zealand. There is no evidence of a community transmission outside of family members in New Zealand, but of course we are constantly reviewing the situation based on the advice of scientists, doctors, and experts, and I’ll be expecting further advice on this today.

Within days the country was to be in suffocating lockdown yet here was the Minister of Health defending large gatherings planned for that very upcoming weekend on the basis that there wasn’t any evidence of community transmission.

What was it about those events that emboldened the Ardern administration to take such risks with New Zealanders’ lives? By the way, in referencing such “risks” I’m assuming the government did actually believe modelling of around that time that they later relied upon to justify so much wrecking and ruination.

Either way, how absurd for anyone in authority to use a supposed lack of community transmission to justify such a jaunty approach. How could there have been evidence of community transmission at that time, whether or not it was actually occurring, given that so little testing was being conducted? More on that soon.

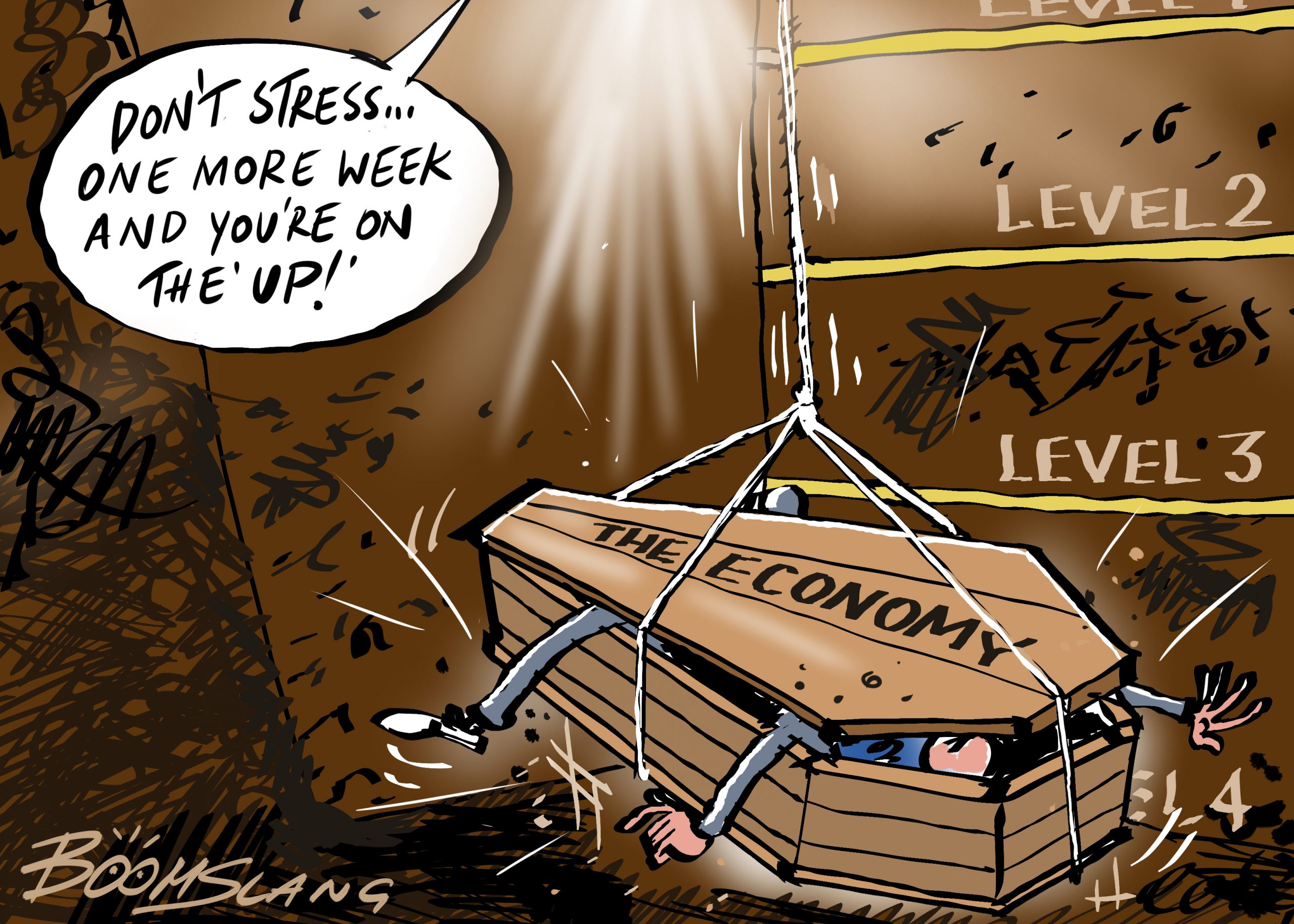

Not on the level

Let me be clear: I was in favour of locking down the country in some way, shape or form at around the time that the government did that. And that was the message given by the National Party at the time, too.

Let me be clear on another point as well, however: the extent of the lockdown appeared inconsistent with the reality of the public health reality towards the end of the Level 4 lockdown, as originally scheduled.

This is another aspect of the absurdity of Cabinet’s decision to extend the Level 4 lockdown.

As we approached the scheduled end of Level 4, there were no widespread outbreaks and new clusters. The significance of this observation is that the official guidelines about the Alert Levels included this as one of the criteria for Level 4.

Without that threshold being met (and a greater period than 14 days already having elapsed in Level 4) there was no good reason – by the government’s own measure – to remain at Level 4 a minute beyond its scheduled end.

The reality by late April, as intoned solemnly daily at 1 pm, would have been better described in the following way: “Household transmission could be occurring” and “single or isolated cluster outbreaks” likewise.

Interestingly, those were the two criteria for Level 2. Yes, Level 2.

In other words, if the government’s own guidelines had been followed – by the government, I emphasise – then we should have transitioned at the end of Level 4 straight to Level 2.

As it was, the authorities decided that we would (eventually) be allowed to live under the Level 3 constraints instead.

This was despite the Prime Minister declaring victory to the extent that we had successfully eliminated the virus, at least “for now”.

More on that word “eliminated” and its multiple meanings later.

While Ardern was happily contradicting herself on this front, she began to repeat a mantra about the possibility of movement between Alert Levels:

The worst thing we can do for our country is to yo-yo between levels, with all of the uncertainty that this would bring. We need to move with confidence. And that means following the rules.

Again and again, Ardern justified the country being locked down at the wrong level (according to her government’s own estimation, remember) using that “yo-yo” schtick.

In fact, “the worst thing” that her government could actually be doing “for our country” was having us locked down at the wrong Alert Level relative to the real world.

If the regime was too liberal, we’d be risking public health in relation to covid-19 (albeit not in relation to other health outcomes).

If the regime was too conservative, on the other hand, we’d be exposing the country to various other risks, along the lines already discussed in this book, including mental health, other non-coronavirus health outcomes (such as hundreds of cancer sufferers going undiagnosed), jobs and livelihoods more generally.

Of course, these are difficult decisions for a government to make but what many Kiwis quietly found objectionable was the Beehive’s bluster.

Ardern’s justification for wishing to avoid the yo-yo scenario was laughable: she wanted to avoid confusion, apparently. If confusion was really a problem as far as her government was concerned, then they would have tried a bit harder to create conditions for life under the Alert Levels that weren’t so, well, confusing.

Simply stated, there was greater harm caused by New Zealand being locked down unnecessarily tightly for unnecessarily long than there would have been if we’d gone to a lower Alert Level and later – if need be – gone back up.

In the words of Martin Berka, a professor of Macroeconomics, Head of School of Economics and Finance at Massey University:

International epidemiological policy models of COVID-19 predict that countries will go through cycles of easing and tightening restrictions.

Intuitively, this makes sense. Even Kiwis much less qualified in examining policy models than Professor Berka would have known that a couple of factors could easily see us needing to adopt a more defensive posture later, no matter how successful initial efforts to eradicate or eliminate might have been.

One of those factors was the weather inevitably worsening with the onset of winter.

Another was the re-opening of New Zealand’s border eventually to the rest of the world.

By describing a potential move up and down levels as “the worst thing we can do for our country”, Ardern deemed it worse than the loss of New Zealand’s entire tourism industry and with it tens of thousands of jobs.

After all, re-opening the border any time in the next year or so, even in modest fashion, will risk us re-importing the coronavirus. Should we not move back up to Level 4 if that’s the case? Apparently not, says Ardern, as that would be “the worst thing” and therefore to be avoided at all costs. Tourism industry, take note.

Eventually, the country did get flipped from the frying pan of Level 4 to the fire of Level 3. This was reported with breathless excitement by the New Zealand Herald thus:

New Zealand has moved today to a slightly less-restrictive way of living with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern declaring the coronavirus “currently eliminated” – and the country’s efforts now the focus of international attention.

- newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2020/03/coronavirus-health-minister-defends-health-officials-tool-moshpit-claims.html

- parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/combined/HansD_20200312_20200312

- Email from “Jacinda Ardern, Labour [email protected]” dated 20 April 2020 to undisclosed recipients; “Update: COVID-19 Alert Level”

- stuff.co.nz/business/opinion-analysis/121099329/protecting-lives-and-livelihoods-data-on-why-new-zealand-should-relax-strict-covid19-lockdown-next-week

- nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12327811

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.