When science fiction authors William Gibson and Bruce Sterling made Victorian inventor Charles Babbage’s “Difference Engine” the centrepiece of their novel of the same name, it was a reminder that many “modern” inventions have long, long histories.

Babbage and co-inventor Ada Lovelace’s Difference Engine, and its even more ambitious cousin, the Analytical Engine, were 19th century computers, in every sense of the word. Even though, due to lack of funding, neither was ever built, the Analytical Engine would have featured an arithmetic logic unit, control flow in the form of conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory.

All before even the first telegraph system was even constructed.

The list goes on: the first patent for a device to send images by wire – a fax machine – was lodged in 1843. Wirelessly-transmitted newspapers were commercially available in the 1930s. The first digital audio player design was patented in 1979.

Even streaming music, surely the most modern development in music, dates back to the 19th century – at almost exactly the same time as radio.

In 1897, the year Marconi built the first radio station in Britain, American lawyer and inventor Thaddeus Cahill patented the dynamophone, later known as the telharmonium. The telharmonium used telephone networks to transmit music from a central hub in Manhattan to restaurants, hotels and homes in the city. Operators could connect subscribers to the telharmonium and the “server” – the telharmonium “music plant” – would stream from their phone receiver. A large paper funnel fitted to the receiver served as an amplifier.

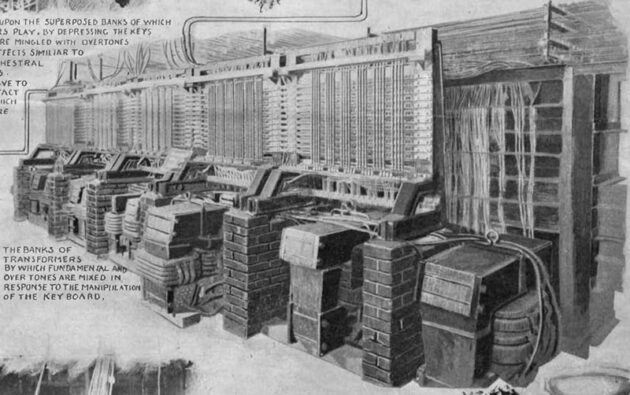

The music plant occupied an entire floor of a building at Broadway and 39th Street. It took 200 tons of machinery – rotors, switchboards, alternators and transformers – to generate the music. On a separate floor, musicians played customised keyboards connected by wire to the machinery. Pressing a key operated a switch which turned on a particular dynamo. The dynamo generated electric pulses which the telephone receiver turned into sound waves.

According to electronic music enthusiast and experimental instrument designer Andy Cavatorta, the telharmonium service “had two players playing continuously, 24 hours a day. It was a sort of weird, non-stop eerie telharmonium music, including a lot of pieces that were composed just for the instrument.”

The telharmonium service became available to the public in 1907, having successfully run in hotels and restaurants. Thaddeus Cahill had grand plans to expand the coverage and available content of the service. But that’s where its technological limitations – and economic reality – came in.

The music plant had to power each of its dialled-in subscribers’ telephone earpieces. As coverage and subscribers expanded, power demands increased likewise. “If suddenly you thought you could get an extra 10,000 subscribers, you’d have to build a new power plant in order to accommodate them,” says Cavatorta. Power losses resulted in faint or distorted music for subscribers. Telharmonium broadcasts leaked into adjacent lines, causing voice calls to be regularly interrupted by music.

Ultimately, the telharmonium business folded in 1916 and in 1920 the 200 ton music plant was dismantled and removed.

Unfortunately no recordings of telharmonium music survive, but a 1906 New York Times article described it as “scientifically perfect music, capable of reproducing any sound produced by any musical instrument and many more that no musical instrument produces”. No less a critic than Mark Twain raved that “I couldn’t possibly leave the world until I have heard this again and again”.

But the telharmonium had a long-reaching impact on electronic music. The Hammond organ was built on the telharmonium’s technology. From there, the synthesizer followed. More importantly, the telharmonium created the idea of “virtuality”: music being remotely streamed into your home by the “magic of wonder-working electric forces”. Almost exactly a century after the telharmonium, first Pandora and then Spotify were again streaming music on demand over the wires.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.