That higher education should be completely free is one of the particular fetishes of the modern left. Jacinda Ardern has promised to make university education in New Zealand free by 2024.

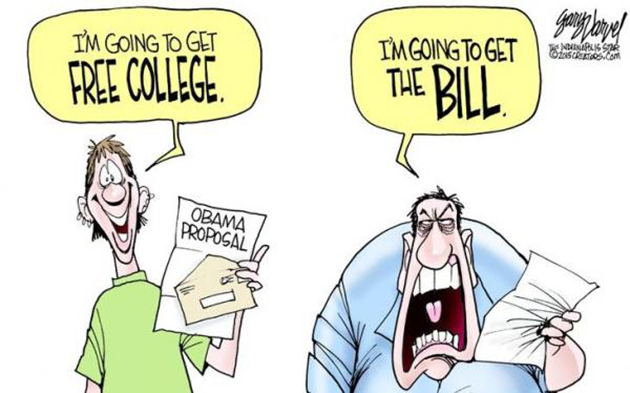

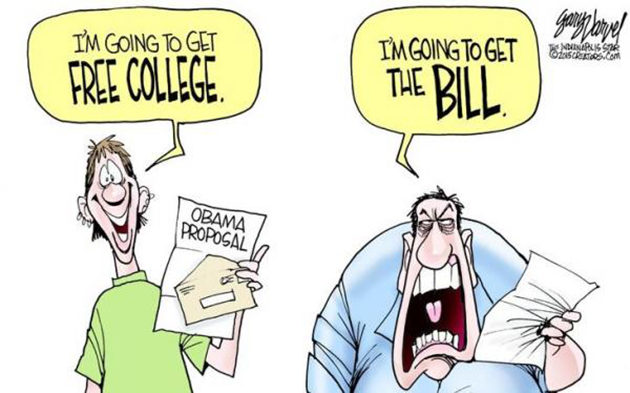

It is merely coincidental, one is sure, that leftist political allegiance is generally the reserve of the young – in other words, those who might otherwise be expected to pay for their own education. Because, of course, “free” education is a myth – what “free” really means, as even leftists from Bill Maher to former Australian Labor Education minister John Dawkins says, is that someone else – taxpayers – foots the bill.

The left, naturally, prefer to characterize their motives as purely altruistic, arguing in terms of equity. Make college free, they say, and the poor will flock to the ivory towers of higher learning.

Noble sentiments, and a beautiful theory – but what happens in the real world?

Australia experimented with free higher education for fifteen years, from 1974, when the left-wing Whitlam government abolished university fees, until 1989, when the reformist Hawke government, introduced the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS). Under the original HECS scheme, students were charged a flat fee that covered part of their course cost, with the government paying the balance. The cost to the student was deferred until their post-graduation income reached a set level, then repaid through the tax system. Allowances were made for up-front fee payment. With some modifications, this is the system in place today.

The Whitlam era of free higher education has become the stuff of legend for the Australian left, for whom Whitlam is little short of a demigod. That his government was never popular, barely lasted three years, and was characterized by chaos and at times high farce is of no matter – the mythology is all.

Perhaps the greatest myth of Whitlam is, as put by broadcaster Phillip Adams, that he magically opened the gates of the universities to working-class students. But as even John Dawkins admits, this just wasn’t true.

Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia from 1949 to 1966, was a great believer in higher education. Menzies not only tripled the number of Australia’s universities, and skyrocketed enrolments, he said, “a university education is not, and certainly should not be, the perquisite of a privileged few,” and “finance should not be the limiting factor where the intellectual capacity and the ambition are adequately high”.

In 1951, Menzies put his money where his mouth was, and introduced the Commonwealth scholarship program. It covered university fees and paid a generous means-tested allowance to poorer students. Menzies also later introduced teacher bursaries. Under these two schemes, eventually 80% of university students were funded by the government.

But this wasn’t enough for the left, and on 1 January 1974, university became completely free for Australian students.

But university remained an almost entirely middle-class pursuit. Enrolments increased, certainly, but not from lower socio-economic groups who were, after all, the target of Whitlam’s reforms. Even Whitlam’s fans admit that he had little impact on equity, but grumble that pointing this out is just “smart-arsing”. Never bring ugly facts to bear on a leftist’s feel-good argument, after all. They prefer “stories”, not data.

But even the primary excuse, that Whitlam’s free education didn’t have time to work, seems ridiculous: the system was in place for fifteen years. What the Whitlam apologists omit to mention is that, as Dawkins says, to enrol in university, students needed to finish Year 12 of high school. In the 70s, very few did, because most could leave as early as Year 10 and take up a trade or other job and go on to earn a perfectly good wage. Even today, with Year 12 education commonplace, trades remain a pathway to high blue-collar incomes.

The other key fact that Whitlam’s cheerleaders conspicuously forget is that making university free abolished the merit component of the Menzies Commonwealth scholarships. Whitlam used working-class taxes to send the children of the middle-class to university without asking them to demonstrate, as Menzies had, that “intellectual capacity … [is] adequately high”.

Even today, university enrolment is overwhelmingly weighted to upper socio-economic groups, with only 16% represented from the lower, a figure which hasn’t changed significantly in decades. The inequity is generational.

Although Year 12 graduation rates increased markedly from the late 80s onward, working-class students remained steadily behind their better-off counterparts. Children with university-educated parents are much more likely to pursue university education themselves. Many of today’s cohorts of students are the children of the Whitlam generation.

The effect of Whitlam’s free university experiment has been to cement a generation of middle and upper-class privilege and status.