As the Chinese Communist Party celebrates its 100th anniversary, it’s putting on a big show of strength. President Xi Jinping is scarcely hiding his ambitions any more, conspicuously dressing up in a Mao Zedong cosplay and ranting threats at Taiwan and anyone else who dares stand in Beijing’s way.

The CCP is giving every impression of a wannabe global hegemon. Yet, for all its bluster and threat, it may be more of a puffer-fish than a dragon.

In many ways Xi’s global bully act is aimed squarely at the domestic audience: portraying an unfairly maligned China pitted against a jealous, racist West is designed to unite the country in nationalist fervour.

But there is another threat to the CCP’s rule – from within.

More and more the Party is resembling the Ancien Régime of monarchical France: a tiny, isolated elite, living in luxurious disconnection from the vast bulk of the people.

While the party can hide from its history, it cannot escape its sociology. General Secretary Xi Jinping heads an exclusive elite of powerful Red-Successor families who flaunt their status and privilege.

For all that its fans in the West vaunt the CCP’s managerialism, the reality is that its history is one of lurching from one policy disaster to another. Mao dragged China from the greatest man-made famine in human history into the lunatic maelstrom of the Cultural Revolution. His successors have only done marginally better. Having encouraged their people to breed as many junior communists as possible, the regime panicked and floundered the other way, introducing the One-Child policy in 1979.

The policy may have saved China from over-population, but its social and demographic effects have been profound: from the “Little Emperor” phenomenon to the stark reality that hardly anyone will be willing to care for its tidal wave of elderly in the next few decades. Reversing the policy did nothing to change demographic trends: from overpopulation, China is now headed for depopulation.

For a time in the Reform era (1979–2009), the party leadership recognised the inconsistency between the socialist and nationalist goals of that original vision and focused on growing the economy, rebuilding the state, and restoring the party’s standing in the eyes of China’s people and the world. On most measures it succeeded.

Economically, perhaps – although the economic benefits have mostly flowed to the coastal cities. While absolute poverty has dramatically declined in China, vast inequalities still remain.

None more so than between the people and the Party.

Many of the top hundred or so dignitaries given pride of place in chauffeuring and seating arrangements at the grand parade in Tiananmen Square on 1 July were descendants of the highest party, military and government leaders of the civil war period and the People’s Republic’s early years—more than half of them powerful and wealthy ‘Red Second Generation’ (hong erdai) figures in their own right. In the popular imagination, China is owned and run by these privileged successors of the early revolutionary era who have no intention of surrendering their grip on power or privilege through system reform. They make up one big ‘party clan’ (xingdang), to quote another of Xi’s favourite expressions.

In placing his party clan on display, Xi exposed two structural defects in China’s social and political hierarchies. First, […]nepotism at the top is regarded as essential for party survival[…]

In the early 1980s, Vice-Chairman Chen Yun [realised that…] ‘If we don’t allow our offspring to take over from us, we’ll be digging our own graves.’

The situation can be seen as analogous to the reforms enacted by the French monarchy in its dying days. Granting limited reform only encouraged the masses to demand more. The CCP is not about to let the commoners set a toe in the halls of power.

But, like the Commons in the 18th Century Estates General, the lower-ranking cadres are starting to ark up.

The second problem with the party’s social formation is the structural separation of the cadre vanguard from the common people of China—or ‘insiders’ from ‘outsiders’, as they are called in China. Mid-level cadres look with envy on the privileges their top leaders enjoy and yet cling to the privileges that distinguish themselves from commoners[…]

These material privileges derive from a more substantial one: cadres and party members are the only people in China entitled to participate in public life and politics. The political realm is off limits to ordinary people. In a public essay published in 2018, Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun noted that ordinary people look on cadres’ special rights and privileges ‘with mute and heartfelt bitterness’. He was jailed for saying it.

The CCP is living in an uneasy truce with its own people. The Party stakes everything on its “Harmonious Society”. As long as the Chinese people are kept satisfied by economic growth, the Party hopes that they won’t be interested in who’s running the show.

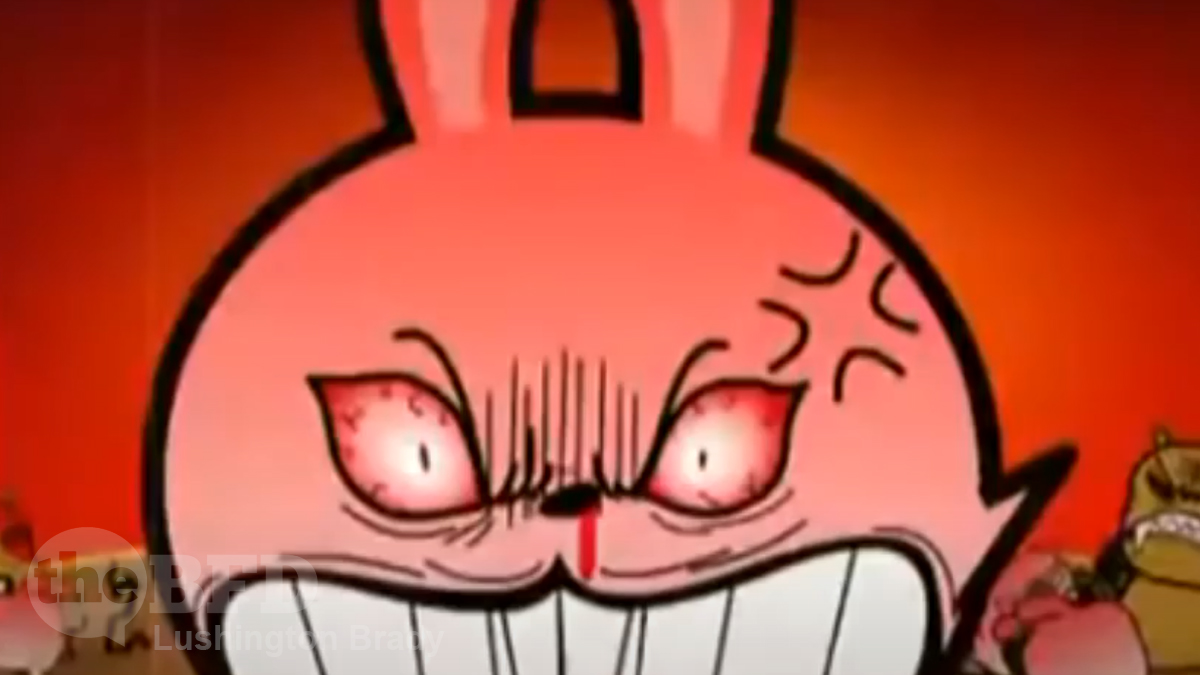

But the Chinese people are hardly passive sheep. When a social media app briefly slipped through the Great Firewall, Mainland Chinese, Hong Kongers and Taiwanese jumped at the chance to talk to one another, uncensored. The 2008 tainted milk scandal came close to cracking the facade of the “harmonious society”. A savagely critical animation depicting the ruling elite as tigers brutally oppressing rabbits, who rise up in rebellion, went viral before it was hastily banned.

That’s what the Party is really afraid of – a billion rabbits realising that they are collectively stronger than the tigers.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD