Graham Adams

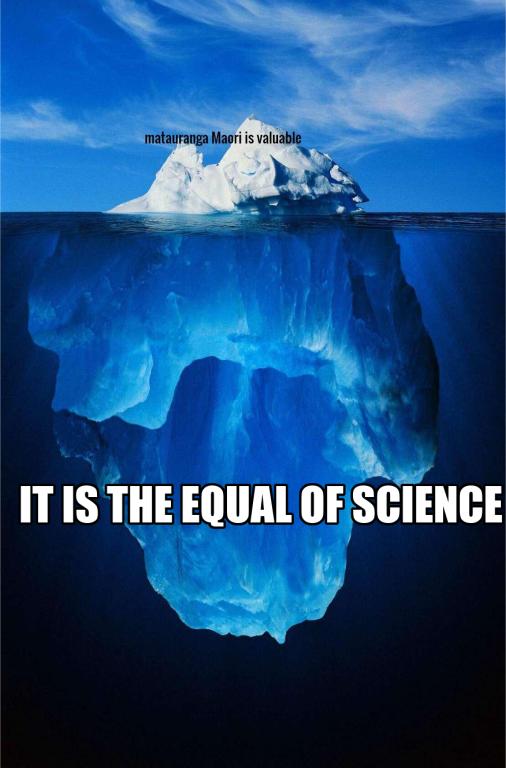

There is a lot of funding and influence riding on successfully casting indigenous knowledge as equal to science. Graham Adams says the debate over the NCEA science syllabus is only the tip of an iceberg.

Anyone trying to get a grip on the matauranga Maori debate over the past several months is likely to be completely puzzled by now.

The incendiary stoush was sparked last July by seven eminent professors stating in a letter to the Listener that indigenous knowledge is not science and therefore does not warrant inclusion in the NCEA syllabus as being equal to science.

Yet in the five months, since the letter was published, virtually no one among those opposing the professors has argued convincingly that matauranga Maori is scientific (even if some small elements of it could be called proto-science or pre-science).

On the face of it, the debate by now should have been declared a clear win for the professors and their supporters.

In rebuttal, their principal critics — including the Royal Society NZ, Auckland University Vice-Chancellor Dawn Freshwater, the Tertiary Education Union and prominent Covid commentators Drs Siouxsie Wiles and Shaun Hendy — have not gone beyond asserting that matauranga Maori is a valuable and unique system of knowledge that is complementary to science.

This view is not contentious in the slightest — and was explicitly endorsed by the professors themselves in their letter.

So, if most everyone agrees that matauranga Maori is mostly not science but is nevertheless a worthwhile and complementary form of knowledge, the obvious solution to the standoff over including it in the NCEA curriculum would be to teach it as a component of, say, social studies. But not as part of the science syllabus.

That way, you’d think, everyone wins — Maori knowledge would be taught in secondary schools, and the argument over whether it is sufficiently scientific would vanish.

However, a simple accommodation of this kind was never going to be possible because the NCEA syllabus is merely the tip of a large iceberg of policies to recast our entire science education system — from schools to universities to research institutes — as an equal endeavour between Maori and non-Maori in which matauranga Maori is everywhere accorded the same status as science.

If more and more of the public come to believe matauranga Maori is not worthy of inclusion in NCEA science, the whole agenda built on the premise that indigenous knowledge is equal to science — and therefore worthy of similar amounts of research funding — will come under pressure.

The NCEA syllabus represents just one small step in fulfilling a much wider co-governance programme based on a radical view of the Treaty as a 50:50 partnership between Maori and the Crown. For that reason, advocates of incorporating Maori knowledge into the science curriculum cannot afford to concede even an inch of ground to the professors and their supporters lest their stealthy revolution be undermined.

In short, the push to promote indigenous knowledge cannot be allowed to fail at any level for fear it will fail at every level.

The project to gain parity for matauranga Maori throughout science education and funding is detailed in Te Putahitangi, A Tiriti-led Science-Policy Approach for Aotearoa New Zealand.

Published last April, it can be seen as a companion to the revolutionary ethno-nationalist report He Puapua and shows how a radical overhaul of the education system could, or should, be implemented.

Supported by no less a luminary than the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor, Professor Dame Juliet Gerrard, it is a roadmap for embedding matauranga Maori throughout the entire framework of science education and policy.

As with He Puapua, the authors of Te Putahitangi make it clear that Maori knowledge should be “elevated to equal status with Western science across the country’s research organisations”.

They also make clear that what is required goes far beyond a “partnership” with the Crown. Their report states:

“Being around the table in a partnership model on the mana of the Crown is not really tino rangatiratanga. We want them to lift out the resources and let us govern ourselves” — which means to be “supported, but not governed, by the Crown”.

Furthermore, Te Putahitangi recommends the “resources” (read “money”) put under direct Maori control should not be determined by the proportions of Maori and non-Maori within the research community:

“Article 3 of Te Tiriti means Maori must have access to resources to support levelling across the science system. One important resource is funding, so funding agencies should ensure policies are in place to allocate budgets for Maori-led research. These funding models should be based on Te Tiriti principles, rather than population proportionality within the broader workforce.”

A footnote to this paragraph indicates that a 50:50 split between Maori and non-Maori funding may not be enough either with what look like punitive damages forming a part of the programme. The recommended funding apparently needs to redress what the authors see as discrimination and persistent underfunding of Maori science over the past two centuries:

“A restorative justice approach to resource allocation, for example, would recognise that recovering from almost 200 years of discrimination will require significant resource and that a rebalancing is needed to compensate for the overfunding of Western science during that time.”

Just as the media have dismissed He Puapua as of little importance — despite its recommendations having been inserted into a raft of legislation — it is likely Te Putahitangi’s role as a roadmap will be similarly ignored. But the influence of the sorts of ideas it promotes can be seen already in government funding — and it makes no bones about the objective.

On the report’s penultimate page, we find the (literal) money quote where it reminds readers that “hundreds of millions of dollars of research funding is at stake”.

Matauranga Maori is already an important avenue for winning research grants — from the $80 million Marsden Fund to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s $2-million-a-year Te Punaha Hihiko: Vision Matauranga Capability Fund.

It has also been firmly inserted into the criteria for determining who gets grants from the Performance-Based Research Fund — the principal source of government cash for universities and other tertiary organisations that was worth $315 million in 2020-2021.

Extraordinarily, in the new PBRF criteria, research into Maori knowledge has been given pole position for the highly contested grants. It now has a research funding weighting of 3 — up from 1. To put that into context, engineering and clinical medicine, which are the most expensive research subjects, have a weighting of 2.5.

The criteria also rate work by Maori researchers at 2.5 times the rate of non-Maori academics.

What this provision will mean in practice is not entirely clear. However, one senior academic described the situation like this:

“The PBRF allocation that each university receives is distributed to departments according to the quality of their research. That quality is measured objectively by criteria like how many publications an academic has in a journal.

“The quality of the journal is also taken into account — is it a major international journal that only publishes the very best research or a local one that publishes almost every submitted article?

“Now, if a department has 10 per cent of Maori academics then that department will generate 25 per cent more funding from the PBRF allocation (ie a 2.5 weighting) regardless of the quality of their research.

“This means that departments will want to employ more Maori researchers no matter how capable they are — which will have significant staffing implications.”

The Ministry of Education announced these changes last year as being motivated by a desire to reduce “inequities” and to improve “recognition of the contributions of Maori researchers and research”. It also justified them as a “better reflection of the partnership between Maori and the Crown”.

In short, academic brilliance and research prowess can be trumped by ethnicity in the name of diversity, equity and inclusion.

As a result of the changes, some tertiary institutes will gain and some will lose. Government modelling shows that the University of Otago would lose $1.9 million, or 5 per cent, of its share of the PBRF fund while Massey and Canterbury universities would each lose more than $500,000.

However, Te Wananga o Aotearoa’s funding would rise from $174,149 to just over $1 million, while Te Whare Wananga o Awanuiarangi would go from $160,473 to $495,928.

Last October, the government also announced that it intends to revamp the nation’s Research, Science and Innovation (RSI) framework while further consolidating the role of matauranga Maori.

The Te Ara Paerangi — Future Pathways Green Paper was presented as the first step in a wide-ranging consultation over science and research policy but it left no doubt about the role it sees for indigenous knowledge:

“A modern, future-focused research system for New Zealand must strengthen the role of Maori in the system and consider how the system achieves outcomes for Maori. We need to embed Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Te Tiriti) across our RSI system, better enabling matauranga Maori and the interface between matauranga and other forms of research.”

Looking through a wide-angle lens at the determined push to give parity to matauranga Maori throughout the science research system, it is easy to see why the professors’ view that it isn’t sufficiently scientific to be included in the NCEA curriculum has been so contentious and so roundly denounced by the educational establishment.

• The deadline for feedback on the Green Paper is 2 March 2022.