Some time ago, I read a “listicle”-type article on “movie villains who were right all along”. My science lecturer at university likewise pointed out that the “villain” from 2012, White House Chief of Staff Carl Anheuser, was also right at several key points of the plot.

Similarly, watching Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society, we’re clearly supposed to think that the stuffy school administrators are the villains. We’re obviously supposed to cheer on Robin Williams’ hero as he encourages the students to throw away their textbooks and “think for themselves”. Yet, even watching the movie in the 80s, I couldn’t help but feel a gnawing twinge that the stuffy principal was more right than wrong, when he admonished: “Prepare them for college, and the rest will take care of itself”.

Because, for centuries, that was the way Western education systems worked: primary and most of secondary school dedicated to teacher-directed education with a great deal of rote-learning of facts, giving a solid base of knowledge to progress from, for those who went to university. It was a system that generally worked well, creating a literate, numerate population.

Not any more. British children today have lower levels of literacy and numeracy than their grandparents. The story is much the same in the US and Australia. All this as we spend more and more billions on education every year.

Why? Education researcher and primary school teacher Greg Ashman believes Australia’s educational decline is in large part due to a suite of teaching methods loosely described as “progressive education”. Progressive education is not synonymous with progressive politics; rather, it is an approach to teaching that prioritises skills-based learning over memorisation.

In The Brain That Changes Itself, Norman Doidge writes: “Up through the 19th and early 20th centuries, a classical education often included rote memorisation of long poems in foreign languages, which strengthened auditory memory (hence thinking in language) and an almost fanatical attention to handwriting, which probably helped strengthen motor capacities and thus not only helped handwriting but added speed and fluency to reading and speaking. Often a great deal of attention was paid to exact elocution and to perfecting the pronunciation of words. Then in the 1960s educators dropped such traditional exercises from the curriculum because they were too rigid, boring, and ‘not relevant’. But the loss of these drills has been costly; they may have been the only opportunity these students had to systematically exercise the brain function that gives us fluency and grace with symbols.”

I certainly remember spending hours dutifully copying lists of words and reciting times tables. Sure, it was pretty dull stuff — but I ended up with a vocabulary in the region of 40,000 words and an ability to almost instantly recall basic multiplications. Most adults my age would be able to say much the same.

But kids aren’t taught that “boring” stuff any more — and it’s showing.

The most widely valued skills in progressive education are not fluency and grace with language or mathematics, but the higher order skills of critical thinking and problem solving.

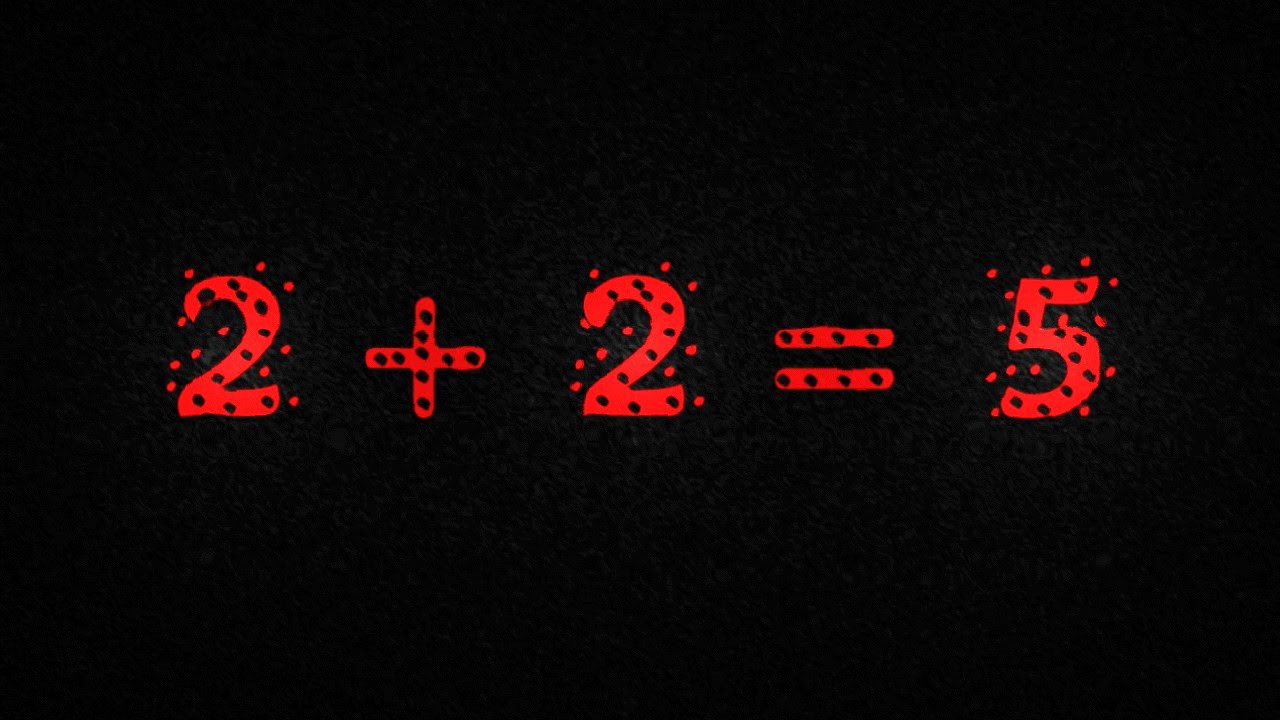

Note that phrase: higher order skills. There’s a reason they’re “higher order”: they’re harder to do. Thinking that kids can learn higher-order skills without slogging through the lower order ones is like thinking that a three year old can get on a bike and go straight to competing in the Tour de France.

Another teacher […] reports that “There are fabulous teachers trying to make their classrooms more relevant and engaging, and schools adopting programs to enhance skills and more real-life experiences, but there are still many, many classrooms that have a teacher at the front of the room, kids sitting in rows being asked to regurgitate information without thinking, analysing, critically or creatively problem solving to come up with solutions”.

The only problem is: how are kids supposed to analyse a subject they know nothing about?

Psychologists suspect we can only think critically about a subject after we have accrued some deep knowledge in it. This makes intuitive sense. To think critically about 19th century English literature you would need to have read Dickens, the Brontes, Hardy and more. To think critically about trigonometry, you would need to have developed some deep mathematical knowledge. Critical thinking does not occur in a vacuum.

A vacuum, in fact, would seem to describe the heads of modern students. I’ve come across university students — good little Marxists, all — who only vaguely recognised the name “Mao”. Theodore Dalrymple describes talking to a university student “studying genocide” by watching the movie Hotel Rwanda. Neil Ferguson notes that the UK modern history curriculum only studies WWII, and that in only the most cursory fashion, focussing entirely on the Holocaust.

Which is not to say that knowing about the Holocaust is a bad thing, but when that’s a student’s entire knowledge of the 20th century, it’s no wonder that we’re dealing with a generation who think that calling everyone they disagree with “Nazis” is the acme of informed debate.

The notion that critical thinking is a skill that cuts across domains is a fallacious one. Expertise in one area often corresponds with blindness and ignorance in another. Such epistemic overconfidence leads epidemiologists to pontificate on racism and medical doctors to sound off about climate change.

Or, indeed, physicists and glorified lab technicians to pose as epidemiological experts.

The educational mania for soft skills comes from a place of good intent.

The Australian

I must respectfully disagree: I rather suspect that a generation of perpetually-indignant ignoramuses is exactly what “progressive” educators want.