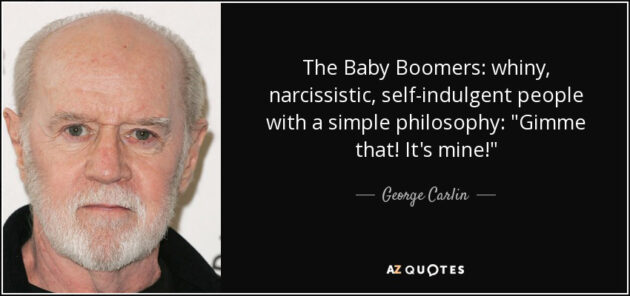

As a Gen Xer, I was born with the instruction to “Wind up Boomers at every chance” practically printed on my birth certificate. So, when another self-congratulatory Boomer post appears on The BFD, naturally I owe it to my generation to post something to wind up the Boomers. Which, let’s face it, is like shooting fish in a barrel: for a generation who deride their own children for being “triggered”, watching them meltdown over a silly meme like “Ok, Boomer” is hilarious.

Gen Xers are the Bobby Bradys to the Boomers Jan and Greg. We’re the easy-going, fun-loving and puckish youngest children of the Post-War family. Although we’re by the necessity of birth order constantly forced to compete with our elder siblings for our share, our manner of competition is usually mischievous, however nihilistic and cynical a front we may cultivate. It’s little wonder that the Boomers icons are whining narcissists like Bob Dylan and John Lennon, while Gen X’s are Johnny Rotten and Kurt Cobain.

Or maybe Elon Musk.

Because one of the defining traits of Xers which has emerged in our middle age is entrepreneurialism. We are, demographer Bernard Salt says, the “just get on with it” generation.

That “just do it” Gen X attitude long predates Nike’s co-opting of the slogan. The mission statement of punk was “Do It Yourself”. Punk fanzine Sideburns exemplified the mission with their famous cover, proclaiming: “This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. Now form a band.” We carried that injunction through the 80s: if the Boomers running the media and record industry weren’t going to let us in, well, hell, we’ll just do it ourselves.

As Henry Rollins relates, in the documentary Punk: Attitude, informal networks sprung up around the country and the world. People booked gigs for their friends in bands, formed their own record labels and distributed them by mail or on foot, saved up for a VHS camera and began shooting videos. The fanzine (self-published magazine) was the written medium of choice.

By the 90s, those informal, ad hoc networks had become legitimate and successful businesses. Instead of being handed a university education and a secure job at The Company on a plate, Gen X paid their own way and learned by doing — without endlessly celebrating ourselves for doing so.

Salt identifies other cultural peculiarities of Gen X:

I have always regarded Generation X as a kind of mortar between the Boomer and Millennial Besser blocks of Australian cultural life. All generations must deal with change but perhaps none more so (in recent times) than the adaptable Xers. Older Australian Xers will remember the introduction of colour television in the ’70s, the introduction of Bankcard and Medibank and the arrival of US fast-food outlets. And their mothers were among the first women to go back to work after marriage and/or children; this factor alone did much to improve the quality of life at the household level. It also enabled young Xers to see the connection between shared parental work and family lifestyle rewards.

Others from this generation will recall the introduction of no-fault divorce in the mid-’70s. I think this, plus the embrace of further education, combined to enable Xers to do something that Boomers never did: push out the age at first marriage (or never marry at all).

Xers invented the concept of an almost tribal friendship circle extending throughout their twenties.

But, above all, Salt sees Gen X as the quiet achievers.

A modern Australia was taking shape and Generation X was adapting without fuss or fanfare. What strikes me is that all this was developed largely with a culture of good humour. I’m sure there was anxiety and frustration, but it was never sufficient to dominate popular culture. Maybe Xers were too pragmatic to be dropouts. Maybe they never saw the need to overturn Boomer-inspired lifestyles – the yuppies and DINKs, the pursuit of a seachange or a treechange.

But Generation Xers left their mark in important ways. They colonised the inner city in vast numbers in the early ’90s, setting the scene for hipster Millennials, two decades later, to personally embellish this movement with their beards and bicycles.

Most Xers didn’t complain too loudly when tertiary education fees were reintroduced from 1989. Or when they toiled in the workforce under Boomer managers who benefited from the long boom following the early-’90s recession, only to be handed the reins around the time of the 2008 global financial crisis. Now, during the pandemic, it is Xers who are of an age to be worrying about jobs and teenage kids and saving for retirement.

While, as The BFD post noted, Boomers are packing up and taking all the goodies they’ve carefully hoarded for themselves for the last half-century, and loading their ugly RVs to “spend the kids’ inheritance”. Having themselves inherited the hard-won gains of their own parent’s blood and toil, Boomers wouldn’t think of doing the same.

As always, it’ll be left to Gen X to quietly pick through the ruins of the mess the Boomers have made: from cleaning up the old bongs our brothers left under the bed when they left home, to repairing the damage done by the political panic to be seen to be doing something about a disease which almost exclusively threatened the Boomers.

Gen X exemplifies the kind of Just Do It culture we all need to give Australia the best chance of recovering in the 2020s.

The Australian