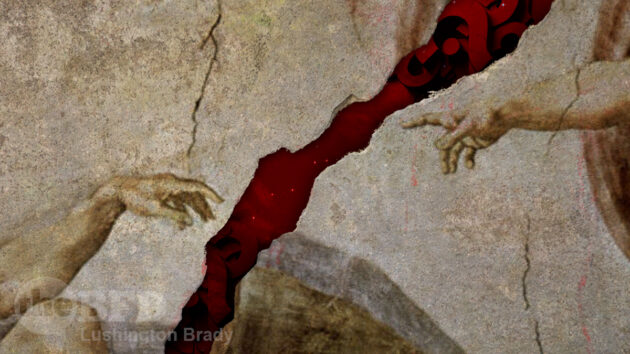

In last week’s Insight, I examined how the West has been “progressively” (pun intended) de-Christianised. In one of the most extraordinary cultural shifts in history, in just half a century, the number of self-identified Christians in the West has plummeted.

In abandoning Christianity, though, I argued, the West is in grave danger of losing, perhaps forever, something essential.

Some atheists have attempted to find a replacement for Christianity as a cultural bedrock for the West. Their efforts have been conspicuously unsuccessful.

Trying to ground a culture in science alone, for instance, is fundamentally mistaken. This is no fault of science: it’s excellent at what it does. It’s just that what it does is completely different to what religion does.

Unlike religion, science is not a normative set of beliefs. Science has nothing to say about what we should do. Certainly some make the mistake of thinking it does: we call that scientism, and it’s a shockingly flawed ideology.

This was the basic mistake of Sam Harris’s otherwise often excellent The Moral Landscape. Harris did an exceptional job of arguing that the most basic human values — those which encourage human “flourishing” — are universal, at least for our species. But, when he tried to claim that science can “determine” those values, he slipped over the edge into scientism.

Philosopher Alain de Botton had another go, in his Religion for Atheists. De Botton, unlike many atheists, at least conceded that religion has many benefits for human beings. But his suggested, atheistic, replacements are unconvincing, even embarrassingly trite.

But de Botton is not the only atheist to recognise the value of religion. Nor is this yearning after faith merely the cri de coeur of relapsed believers. Historian Niall Ferguson, for instance, states that he “was brought up an atheist — I didn’t become one”. Yet, he now argues, “I do think we should go to church”.

Ferguson is just one of several prominent atheists who are starting to realise that, in abandoning Christianity, Western civilisation has hollowed out its soul. Roger Scruton and Douglas Murray are likewise unbelievers who became, in Murray’s words, “uncomfortable agnostics”. Scruton thought that Christianity, especially its concept of forgiveness, was in many ways the soul of Western civilisation.

As I’ve written elsewhere for Insight, despite rivers of philosophical ink being poured on the problem, all efforts to derive a rigorously logical ethical framework — atheist or not — have simply failed. Ferguson is blunt about atheism’s failure: “you can’t base a society on that. Indeed, atheism, particularly in its militant forms, is really a very dangerous metaphysical framework for a society.”

Of course, it is just as true that deductively deriving ethics from God runs up against as many logical problems as atheism. But religion has at least one clear advantage when it comes to sorting through the messy, illogical problems of human morality: thousands of years of practical experience.

“I’m a big believer,” says Ferguson. “That with the inherited wisdom of a two-millennia old religion, we’ve got a pretty good framework to work with.”

Disparagers of Christianity tend to harp on long-gone dogmas and schisms (much as disparagers of American nearly always yammer about racial laws that were abandoned half a century or more ago) or focus on the wrongdoings of a very small number of church officials (statistically, in fact, less frequent than their counterparts in secular institutions such as education). But Christianity has had over two thousand years to get a great many things right. More importantly, it has shown an often astonishing ability to adapt where necessary.

Most importantly though, Christianity (and religion in general) speaks to a facet of human experience that science does not and cannot. As philosopher Hilary Putnam puts it, “When properly understood, science and religion can be viewed as separate and complementary endeavours, asking very different questions and pursuing very different ends”.

On Putnam’s argument, the way in which human beings experience the world is “perceptually and conceptually subdivided in a certain way”. The separate cognitive realms in this division each satisfy a different realm of human experience. Putnam argues that science is rooted in what he calls vernunftig, or discursive rationality: that is, knowledge obtained by reason and argument rather than intuition. Religion, on the other hand, is embedded in verstandesgemass, or intuitive understanding, or faith.

As Hume might have argued, science tells us how the world is, religion tells us what we ought to do about it.

Atheistic ethical systems have, it is true, tried to do the same but, with all the best intentions, they’ve done a pretty lousy job of it. This is, again, not to say that atheists can’t be as perfectly virtuous as anyone else, but that is often in spite of attempts at deriving atheistic ethics.

Religion, in the end, just seems to satisfy our natures in a way that atheistic systems do not. Indeed, many atheistic systems often tacitly owe their bedrock moral assumptions in large part to the Western Christian heritage. As the born-and-raised atheist de Botton concedes, “It’s clear to me that religions are in the end too complex, interesting and on occasion wise to be abandoned simply to those who believe in them”.

In that case, then, why Christianity? Wouldn’t any religion do?

Possibly, but Christianity is so deeply embedded in Western culture that it just fits Westerners as no other religion does. Westerners’ efforts at adopting “Eastern” religions or, the spiritualism du jour of Western elites, “indigenous spirituality” almost always come across as facile and trite. It’s not so much a matter of “cultural appropriation” as cultural appropriateness.

For all the efforts of the “Coexist” crowd, Islam is often irresolvably hostile to Western ideas of freedom, especially sexuality. Traditional Aboriginal spirituality is tied inextricably deeply to notions of kinship and ties to a specific country that often defy the understanding of those not born and raised in the culture.

On the other hand, Indigenous Australians are among Australia’s most fervent Christians. 73% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders identify as Christian, compared to 52% of Australians generally. Many Aboriginal Australians fuse traditional and Christian beliefs. As journalist Stan Grant puts it, “It was a wonderful adaptation and innovation on our traditional society…We [reconciled] Christian teachings with our own beliefs; it wasn’t hard.”

Christianity, in short, is a bit like an old, well-worn shoe for Westerners — even those who’ve never put it on.

Which leaves, finally, the question of how? How can Westerners who don’t and never have believed in God just start taking a seat in the pews without feeling like utter hypocrites?

To answer that question, we need to look back nearly 400 years. I will examine this path a “re-Christianisation” of the West might take, in the next Insight.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.