In a recent post, I asked: Is it time to re-Christianise Australia? The post certainly generated some lively comments, both for and against. Some of the dissenters raised some good arguments worth looking at. There is also the problem that a short post is simply not enough to examine such a weighty proposition.

So I shall take the opportunity to explain my idea more fully.

Most importantly, I should point out that I am not proposing any kind of theocracy. Nor the kind of narrow-minded, stuffed-shirt “Moral Majority” policies of the 1980s’ “theocons”. So what am I proposing?

First, let’s examine what I see as the problem.

Travel around rural Australia and you’ll see a lot of churches. Not the grand cathedrals of Europe, nor the “Mega-Churches” of America. Instead, thousands of small chapels built of bluestone, sandstone, weatherboard and tin, dot the landscape.

They were once the centres of rural communities. As settlers moved across the landscape, very often a church was one of the first communal buildings erected (even before a pub!). Farmers would raise subscriptions or volunteer their labour to build the chapel themselves.

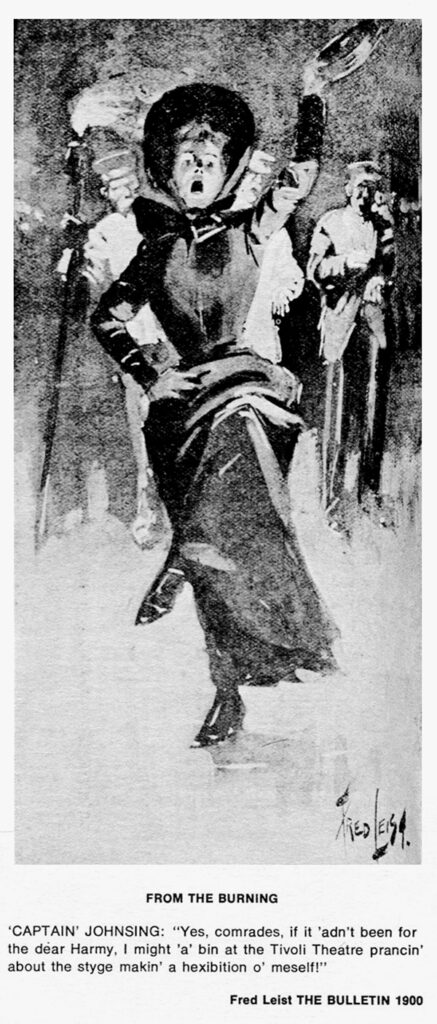

Religion, the Christian religion, was once the centre of communal life – but in a very Australian way. Australians have always nurtured a deep suspicion of pulpit-pounding public displays of religious fervour. Cartoons lampooned the Salvation Army; folk songs mocked “rantin’, ravin’, screechin’, preachin’, cranky, blanky” parsons. Australians were as suspicious of the clergy as they were of politicians. But churches were the communal meeting places. People were baptised, married and buried in their community church.

Australian culture is deeply connected to Christianity in even more ways. From the earliest days of the penal settlement at Sydney Cove, colonial officials saw Christian ministers as “natural moral policemen of society” (probably, thereby, engendering the Australian suspicion of moralistic clergy and pinched-mouth “Wowsers”).

The Australian Constitution invokes “the blessing of Almighty God”. Even today, the Australian Parliament still opens with the Lord’s Prayer, which has only recently been accompanied with an “Acknowledgement of Country”.

Anzac Day, one of our most revered public occasions, has deep, grass-roots, Christian origins. Even today, Anzac Day has an unmistakably Christian flavour: the church-like reverence, the clergymen leading prayers, and the singing of hymns. “There is a general acknowledgement of the existence of a deity.”

Beyond even that, Australian culture is undeniably Western, with all that that implies. It’s not for nothing that, until the modern era, “Christendom” was more-or-less synonymous with the West. Even modern Western secular ideas like individualism, the Enlightenment, and the Scientific Revolution are inextricably intertwined with Christianity.

All that has rapidly changed, over the last half-century or so. Today, many of those thousands of rural churches seem almost like relics, in their lonely paddocks, with their overgrown little graveyards. Some are falling into disrepair, some are converted to modern houses or local museums.

Christianity in Australia has experienced a dramatic decline. In the mid-60s, 88% of Australians identified as Christian. By 1991, that had fallen to 74%, and 52% in 2016. Interestingly, church attendance has seen a less dramatic decline, suggesting that remaining self-identified Christians are tenacious in their faith.

Still, Australia has otherwise become notably secularised since the 1960s. More than that, though, there has emerged a vocal and influential segment of Australian society that is not just non-Christian, but implacably, aggressively anti-Christian. This, in tandem with their overt hostility to the West, as manifested, for instance, in the vituperative backlash from academics against a proposed degree course in Western Civilisation.

Which, if nothing else, demonstrates that even its detractors tacitly acknowledge the intertwining of Christianity and Western civilisation.

In becoming more and more non-Christian, though, Australia, like most of the West, has lost something more than religious faith. We have seen a “progressive” (in more than one sense) hollowing-out of what might be called “the Western soul”. It might be melodramatic to say that the West has descended into a godless abyss, but there is much to defend that view.

When I say that, I am not trying to be some pearl-clutching “Think of the children!” busybody, like The Simpsons‘ Helen Lovejoy. I am not saying that the non-religious have no moral compass: clearly, most of them do (just as some Christians clearly do not).

But, in abandoning Christianity, the West has lost something essential.

Consider some of the most consequential moral and social issues of recent decades. On everything from gay marriage and the transgender tsunami that followed in its train, to the rise of radical Islam, to state-sanctioned suicide, the secular centre-right has either been conspicuously missing in action or more often, it has cravenly surrendered to the far-left.

It’s not that there aren’t good, secular arguments against transgenderism or “right-to-die”, and even gay marriage. The secular centre has just chickened out. It’s been left to the Christians to stick their heads above the parapets, every time.

The enervation of the secular centre and right seems to go hand in hand with the kind of wishy-washy moral and cultural relativism that has accompanied the growth of secularism. Islam is passionately absolutist. The far left may not be religious, but they are (confused and contradictory) moral absolutists of an intensity that would make Calvin blink. Against that, the “Oh, mustn’t judge” relativism of the secular centre is powerless to take a stand.

Secular atheism is not inherently immoral. Non-belief does not make one a bad person. But, try as they might – and some atheists, like Sam Harris, have tried very hard – secularism has yet to come up with a convincing moral framework to rival Christianity.

Despite the decline of Christianity, many secular Westerners still seem to feel a yearning for belief. I have previously called this the “God-shaped hole” in our nature. “Spiritual but not religious” is how a great many non-Christian Westerners describe themselves.

As C S Lewis wrote, “spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison”. The far-left have eagerly gobbled all manner of poisons, from Climate Cultism to Wokeism. Many on the centre and right seem to have settled for spiritual junk food. There’s the superficial worship of the Cult of Celebrity, for instance, or the facile appropriation of “Eastern” religions in a crystal-waving New Age.

Many, especially in Australia, have adopted a bowdlerised version of “Indigenous culture”. I use the quote marks because it’s mostly made-up pap that bears little resemblance to what was actually practised in pre-European Australia. The ubiquitous “Welcome to Country” and “Traditional Acknowledgement” ceremonies now blight every Australian event from football matches to school awards nights. Even the urban, whiter-than-white Fauxborigines who seem to make up the ranks of “Indigenous activism” are unconvincing play-actors.

This hasn’t stopped most non-believers from living just as morally upright lives as any believer. But it has apparently sapped the will of the secular centre-right to fight the big fights. Even some long-time atheists are starting to acknowledge that Christianity contributed something vital to the spirit – no pun intended – of the West.

Something that we are in grave danger of losing, perhaps forever.

I will examine further the attempts to build a post-Christian West, and the path a “re-Christianisation” might take, in the next Insight.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.