Barbara McKenzie

BA (Hons) Linguistics; PhD (German Lit.)

stovouno.org

Barbara McKenzie has a PhD in in German Literature.

It goes without saying that NZ English has borrowed words from Maori (so let’s get that of the way), most notably native flora and fauna, as well as many place names. However, it is now policy to artificially insert into English texts Maori vocabulary. Even whole phrases.

Words that have already been borrowed into English though not in common usage (being mostly used in a Maori context) are now mandatory. For example, the word whanau must replace the word for family in every context, e.g the track and trace notice for Covid-19.

Government texts and media articles are sprinkled with terms that are completely unfamiliar to the majority of New Zealanders, sometimes explained, sometimes not. A goal expressed in the language revitalisation strategy, “Te Reo Maori is seen, read, heard by Aotearoa Whaanui”, uses a term, whaanui, which has probably never before appeared within an English text.

A newsletter of the former Royal Society of New Zealand, now reincarnated as the heavily political body Royal Society Te Aparangi, well illustrates the policy. The newsletter is headed ‘Kia ora from Royal Society Te Aparangi‘ followed by He wahine ngakau mahaki, he wahine toa (translated) and finishes with Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini (translated).

It refers to Aotearoa (not New Zealand) and to Te Whanganui-a-Tara (not Wellington). The text is dotted with Maori terminology such as whare (house, in English more often shed but rarely heard now, meaning in this context incomprehensible), matauranga, mihi maioha, wahine toa. Most are totally unfamiliar – the fact that many are guessable from the context does not make them any the less alien.

TV1’s newsreaders, as well as using Maori greetings to begin the broadcast, regularly use a Maori expression after a commercial break – the context (and only the context), suggests that it means something like ‘welcome back’.

Communication takes second place to NZ-style bilingualism. Where other countries publish important texts either as separate documents, or at least having the languages completely separate, NZ documents like the Maori Language Act alternate Maori and English text throughout, so that they are just about impossible to read online.

Every Text Must Be a Conscious Language Learning Tool

Government texts such as the Department of Conservation’s Biodiversity Strategy have as a primary goal the promotion of the Maori language.

‘Mauri and kaitiakitanga

Mauri is the life principle or living essence contained in all things, animate and inanimate.

Te mana atua kei roto i te tangata ki te tiaki i a ia, he tapu. The concept of mauri reflects ideas of interconnectedness, resilience and wellbeing of nature. Mauri reflects the intrinsic value of nature, but also our obligation to be stewards of its health.

Kaitiakitanga can be described as the obligation to nurture and care for the mauri of a taonga; the ethic of guardianship, protection of that which is sacred. ‘

Through language DOC achieves a romanticisation of the Maori connection to the environment:

‘Tangata whenua are exercising their role as kaitiaki

Kaitiakitanga is the obligation, arising from the kin relationship, to nurture or care for a person, place or thing. It has a spiritual aspect, encompassing an obligation to care for and nurture not only

physical well-being but also mauri. Mana whenua aspire to exercise kaitiakitanga over their ngahere, whenua and moana. However currently there are many barriers to this taking place. In order to strengthen kaitiakitanga there is a need to strengthen relationships between people and nature and

re-establish cultural practices.’

Children of course are fair game: the teachers’ resource for the sexuality education curriculum, Navigating the Journey (manipulative on multiple fronts), makes it clear that that class at least operates as a language learning class.

‘You could encourage your students to use te reo Maori as they talk about their whanau. […] Use the following words in te reo Maori to describe feelings […] Encourage the use of te reo Maori vocabulary for feelings […] The students should be encouraged to pronounce the M?ori names for body parts’ (Years 1-2); ‘Students could practice te reo M?ori phrases to describe how they are feeling (Years 3-4)

Discuss values and concepts for caring for others, such as wairua, whanau, hapu, iwi, whanaungatanga. Encourage the students to consider and share examples of these values and concepts from their own lives, for example, kaumatua caring for their whakapapa, hapu and iwi; sisters and brothers caring for each other, older siblings caring for younger siblings, parents, aunties, and uncles caring for children and so on.

[…] Harakeke has important historical and contemporary uses. Many of the whakatauki and waiata associated with harakeke, such as “Tiakina te pa harakeke” and Hutia te rito o te harakeke, express values that are important to Maori.

Talk with your school whanau group, kuia, or kaumatua about their kaupapa (protocols) around gathering and using harakeke. Make links between taking care of the harakeke and taking care of

people in our classroom, school, and families. (Years 1-2)

The Change of Name to Aotearoa

Aotearoa was one of several Maori names for the North Island: there was no Maori name for the whole country, and when Maori chiefs signed the treaty of Waitangi, presented in Maori, the term used for New Zealand was Nu Tirani. New Zealand continued to be referred to within Maori texts as Nu Tirani or Niu Tirani for another 100 years or so. At some point, Aotearoa became seen as the original Maori name for New Zealand and in recent years there has been a move to change the name to the very clunky Aotearoa-New Zealand. Suddenly, however, without New Zealanders knowing quite how it happened, the government is using Aotearoa on its own as the formal name for New Zealand. For example Jacinda Ardern:

‘Medsafe only grants consent for a vaccine’s use in Aotearoa once it’s satisfied […].’

TV1 News and weather reporters routinely use Aotearoa instead of New Zealand, despite many protests from the public. The upcoming festival of French Films is termed French Film Festival Aotearoa.

There is no democratic mandate for this change. There has been no referendum, and polls consistently show that the public rejects a change even to Aotearoa-New Zealand. There has been no public discussion of the consequences, for example how this will affect New Zealand’s standing in the world.

The Media as an Arm of the Labour/Green Government

In April 2020 the government announced a support package of $50 million for media organisations as part of its ‘covid response’. It subsequently created a Public Journalism Fund, allocating a further $55 million to the media. First of the listed criteria is a ‘Commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to Maori as a Te Tiriti partner’, explained as:

‘Applicants can show a clear and obvious commitment or intent for commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, including a commitment to te reo Maori.’

The taxpayer is therefore funding the media to promote Labour/Green ideology, including Te Reoglish and a name change to Aotearoa.

Disempowerment

‘It seems like a hostile takeover of our country is underway and most people feel powerless to do anything about it’.

Karl Dufresne

These ‘audacious’ measures have no mandate, in that no party, no candidate has incorporated them into a platform and discussed them during an election: for example, there is no mention of WCC’s te Reo policy in this pocket profile of Jill Day, its principle driver.

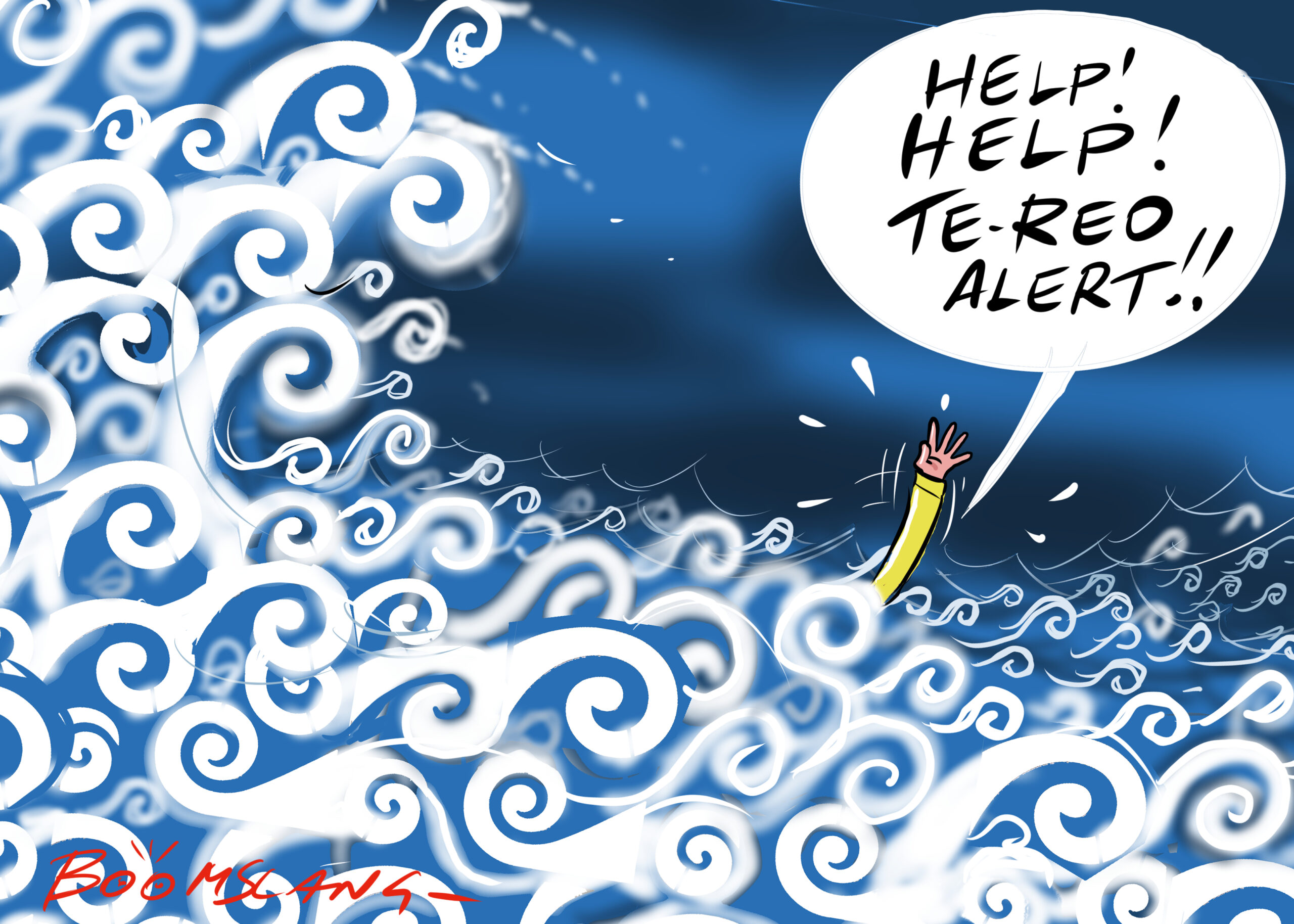

They are a source of frustration to the vast majority of New Zealanders, who have no interest in learning the language – and probably even less now. There are multiple inconsistencies: different rules of usage apply; total respect is demanded for Maori but none for English. They are perverse in that they obstruct rather than facilitate communication.

New Zealand English speakers have no authority over their own language and are second-class citizens when it comes to Maori. Any objective criticisms, any appeal to the norms of language, any comparison with foreign usage, are met with accusations of racism.

Richard Treadgold, a member of the NZ Climate Science Coalition, recently wrote to Cindy Kiro, chief executive of the Royal Society Te Aparangi:

Ahorangi Chief Executive

Dame Cindy Kiro,Thank you for your latest newsletter Alert, Issue # 1146. dated today. An activist production if ever there was one.

I must complain that it is 90% inaccessible and functionally illegible because of the Maori language.

From Ahorangi Chief Executive through Royal Society Te Aparangi to hangarau learning, Matariki hunga nui (no English hints at all with this one) and Pito mata in action, large portions of your once-captivating newsletter are blank to me. Worse, it reeks of activism, with the Society blatantly forcing the Maori language down Kiwi throats. In years past, it never did, so something fundamental has changed, something ugly has taken its place. I feel inadequate, trampled on and excommunicated (emphasis added).

Where Does This Come From?

The divisive policies of the government are consistent with measures applied elsewhere in the world to create disempowerment and racial disharmony. Te Reofication is promoted in New Zealand by adherents of other policies stemming from the UN and the global elite: faux environmentalism (eg ‘climate change’); negation of property rights; the mass movement of people; critical race theory; child abusive education. These are all policies of the New Zealand Labour and Green parties; government departments such as DOC in its Te Mana o te Taiao – Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020 and the Ministry of the Environment in He Kura Koiora i hokia promote Te Reoglish along with undemocratic powers to Maori elites, the erosion of property rights for ordinary people, and climate change alarmism based on junk science.

We can conclude that there is an overriding principle at play. It certainly isn’t the long-term welfare of the Maori people or New Zealanders as a whole.

This is an appalling document, written from a completely subjective viewpoint. It is basically an instruction on how to use propaganda, the government, the education system and our social institutions to force Maori language and culture upon the country. Of course, it also involves massive indoctrination of young New Zealanders.

Did 52% of New Zealanders vote for the virtual cultural conversion of our country? How could they when Jacinda Ardern never told them it was on her agenda.

theredbaiter.com

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.