The latest hoo-ha attaching to our current Prime Minister is the story that there is a film to be made about the Muslim massacre in Christchurch on 15 March 2019, under the title, “They Are Us”. We know who the “They” are. And the “Us” presumably covers the rest of us. But do we of that “Us” really know who WE are, and where we figure in a New Zealand co-governed 50/50 by Maori, according to the prescription of the hitherto secret agenda of the He Puapua report?

Any consideration of this basic institution of nationhood must necessarily begin with the Treaty of Waitangi that was signed in 1840 and was an agreement between the British Crown and a large number of Maori chiefs. Today, the Treaty is widely accepted to be a constitutional document that establishes and guides the relationship between the Crown in New Zealand (embodied by our government) and Maori.

For starters, who better to define the situation of our country prior to 1840 than the great Maori scholar Sir Apirana Ngata, who said this in 1922:

“The Maori did not have any government when the European first came to these islands. There was no unified chiefly authority over man or land, or any one person to decide life or death, one who could be designated a king, a leader, or some other designation. … The Maori did not have authority or a government which could make laws to govern the whole of the Maori race.”

As well as the absence pre-1840 of anything resembling a national governance structure, the name by which we now know our first settlers, Maori, was not in general use signifying them as an interconnected nation of people. When used, as recorded in papers of the Polynesian Society, it was more as an adjective meaning “common”.

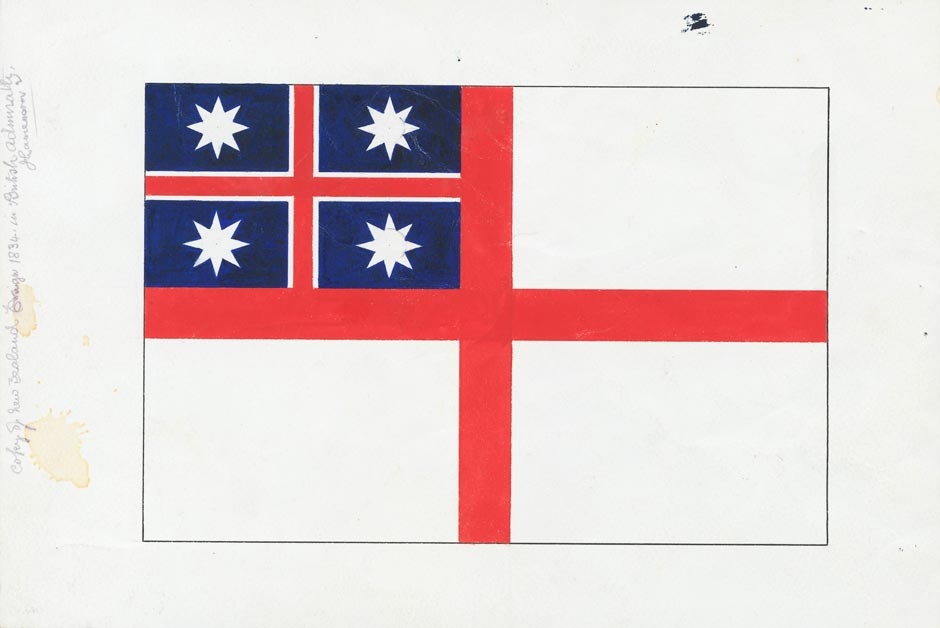

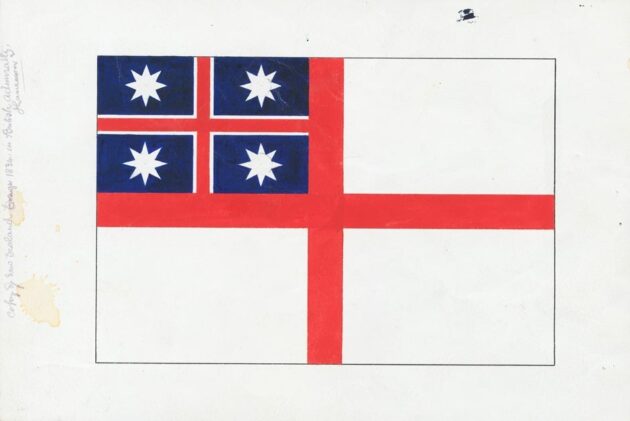

In 1834 a group who described themselves as the United Tribes designed this flag as an ensign:

This was New Zealand’s first official flag. It was selected on 20 March 1834 by 25 chiefs from the Far North who, with their followers, had gathered at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands. Missionaries, settlers and the commanders of 13 ships were also present. The official British Resident, James Busby, made a speech and then asked each chief to come forward in turn and select a flag from three possibilities. The son of one of the chiefs recorded the votes. A flag based on the St George’s cross that was already used by the Church Missionary Society is said to have received 12 votes, the other designs 10 and 3. Busby declared the chosen flag the national flag of New Zealand and had it hoisted on a flagpole to a 21-gun salute from HMS Alligator.

Further, documents issued around that that time by the UK Colonial Office referred to the those first settlers either as “natives” or as “New Zealanders”. Indeed, there is no mention of the term Maori in the treaty. One of the most significant bodies set up post-Treaty was called the Native Land Court. Possibly the first official reference to the term Maori was in the 1860s when Maori men were given the right to vote, on a separate day, for a representative in Parliament in each of the four Maori seats that had been created.

Two other agencies created to preserve rights for Maori were:

- The New Zealand Maori Council established through the Maori Community Development Act of 1962, and

- The Waitangi Tribunal (Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 to make recommendations on claims brought by Maori relating to legislation, policies, actions or omissions of the Crown that are alleged to breach the promises made in the Treaty).

Click on the above link to understand why there was a need for such a tribunal known as Tribal Committees to operate in order to give voice to local and national issues impacting Maori.

If there was one single event that led to the present contretemps created by the current government’s post-election unveiling of its previously hidden agenda of co-governance advocated in He Puapua, it was almost certainly the decision of the Court of Appeal in 1987. In a case brought by the Maori Council in which the president, then Sir Robin (later Lord) Cooke, introduced what were “principles of the Treaty”, one of which was: The Treaty established a partnership, and imposes on the partners the duty to act reasonably and in good faith.

As far as I can ascertain this was the first official mention of the word “partners” in any relation to the Treaty. Our Justice Department website describes the Treaty thus: The Treaty promised to protect Maori culture and to enable Maori to continue to live in New Zealand as Maori. At the same time, the Treaty gave the Crown the right to govern New Zealand and to represent the interests of all New Zealanders. There was no mention of partnership or partners.

It seems to me the time has arrived for action to protect the rights of the “We” – that majority in our democracy who have no claim to the privileged status of Maori. Not that I have any objection to Maori having the degree of privilege that is theirs by right as being our first settlers, and whose enduring presence has endowed us with what’s become our unique Kiwi character and lifestyle. We are all Kiwis, regardless of colour or ethnicity, with what now has become a vibrant multi-cultural society.

So, if we have what we call a “founding document” and we want the principles that underpin the governance of that society in this second decade of the 21st century and beyond to accurately and fairly represent us all as Kiwis, surely it’s time – I would argue, well past time – to review that 181-year-old document. We must ensure that any principles generated by that document not only preserve the significance of our first settlers but also serve the interests of the majority of the “We” who came later and made such a creative contribution to the Godzone New Zealand has become.

Those who may wonder what all this has to do with the Treaty should read what independent commentator Karl Du Fresne says here.

It’s for that reason that I will endeavour to persuade the National Party to adopt the following remit so that we may bring out in the open Ardern’s hidden agenda:

That the National Party includes in its election manifesto a pledge to institute a Royal Commission to study the Treaty of Waitangi to assess whether it may be necessary to re-interpret and re-define the principles of the Treaty to accommodate at all levels of governance the multi-cultural society that has developed from the bi-cultural state of New Zealand in 1840.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.