18th April 2021

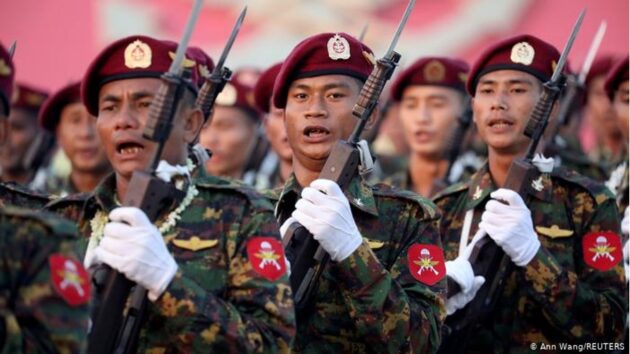

The conflict in Myanmar is reaching a stage where the Military won’t lose, but equally they can’t win. The Tatmadaw have about 350,000/400,000 troops and the EAOs about 100,000. The Tatmadaw are better armed and have an air force, most of which is configured for troop movement and ground attack support. The EAOs will put up staunch resistance in their own areas, hilly and covered in jungle and wouldn’t survive a full-on assault if they were in the dry zone (the central, flattish part of Myanmar).

The EAOs are increasing their strength with recruitment from the ethnic regions, but also from major metropolitan areas whose young people are increasingly travelling to the regions for training. Supply of weapons is not an issue for the EAOs as they will get support from actors in China, Thailand, and India.

To back up the EAOs the CDM’s actions are increasingly freezing the economy. Normal commercial trade has almost come to a stand still and the Military’s investments are no longer acting as a milk cow for the hierarchy.

Myanmar’s army has about 406,000 soldiers in active duty as of 2019, according to data published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. In absolute terms, it’s the 11th largest army in the world.

The Tatmadaw has been the most powerful political player in Myanmar since it emerged as an independent country in 1948, and the army’s influence has continued to grow over the years.

It is the only institution that has endured all challenges and survived with its power intact. Even massive international sanctions in the 1990s and early 2000s made little impact on the generals.

The military’s self-perception and self-confidence are rooted in the nation’s history. “One must not forget that the army is older than the state. It was founded in 1941 in Thailand as the ‘Burma Independence Army’ by the independence hero Aung San, who is still revered today,” Bünte said. “Money and logistical support came from Imperial Japan. Aung San admired Japanese militarism, at least until he defected to the Allies shortly before the end of World War II.”

Until his assassination in 1948, Aung San considered a strong army indispensable, as only it could guarantee the country’s independence and unity. The army’s motto, which is still valid today, originated in Japan. It reads: “One blood, one voice, one command.”

In the years after independence, the military saw its main task as fighting communist and ethnic insurgency movements, and preserving the unity of the country. The military always put security above everything else, developing a “paranoid security complex” that persists to this day, Bünte stressed. “The impression that you are surrounded by enemies has not changed since the founding of the state.”

The military first staged a coup in 1962, when General Ne Win initiated the “Burmese Way to Socialism.” While the socialist revolution failed, Ne Win was successful in completely transforming the political system to suit the military, Nakanishi underlined in his book. This created a strong linkage between the military and the state. A key mechanism here was that officers leaving military service were given posts in the civilian administration, depending on their rank. Generals were usually provided with ministerial posts.

This system remains largely intact today. According to all that is known about the recent military coup, an important factor was that army chief Min Aung Hlaing would have had to leave the military in 2021 and no follow-up post could be found for him in the civilian government. This was partly because the military’s proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), had performed poorly in the November 2020 elections.

But the period after Aung San Suu Kyi’s and NLD’s election victory in 2015 had threatened the model of disciplined democracy in several ways, from the military’s perspective.

The NLD’s civil service reform in 2017 succeeded in breaking the rule that military personnel should be appointed to government posts. And the NLD made no secret of the fact that it would not accept the 2008 constitution.

“Basically, Suu Kyi never recognized the military. She had become part of the political system to change it, but not to implement it,” Bünte said.

With the February 1 coup, the military put a temporary end to the erosion of its power.

Looking at Myanmar, Bünte noted, “Deviation or diversity of voices is seen as a weakness. There is a decidedly strong esprit de corps and a cultural tendency not to disagree with higher-ranking or older members of the (military) community.” However, he added, the military is also like a black box, and it is difficult to judge from the outside whether there are forces that want to reverse the coup.

Source Deutsche Welle 18th April 2021.

Talks of rebellion within the Tatmadaw are difficult to verify, but many of the soldiers have been recruited from age 12 onwards and regard the army as family. They have been brought up in isolation, within separate shops, hospitals and entertainment and are isolated from the civilians who are a threat to their family – the army. They live apart from civilians in cantonments, self-contained. This has bred a kind of sociopathy and even psychopathy within the soldiers. Also, if a soldier defects, they know that it will have consequences for their family.

The police force numbers about 100,000 and is heavily armed and brutal. It is also closely connected with the Tatmadaw, both formally and informally. However, there is one major difference, and this could be a source of trouble for the military.

The police are still embedded in society and live alongside civilians. They are not immune to the economic woes and the disapproval and condemnation from the civilians thrown at their families.

Already, according to unconfirmed reports, they have lost about 3,000 officers who have crossed the borders and some have defected to the CDN supporters and taken their weapons with them.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD