Michael Reddell

croakingcassandra.com

I’ve been bothered for some time by how lightly the Director-General of Health, Ashley Bloomfield, was excused over his lapse of judgement in accepting hospitality from New Zealand Cricket at a time when preferential access to the Covid vaccine for the New Zealand cricket team was a matter of some concern to New Zealand Cricket, and when Bloomfield himself exercises considerable clout in such matters (having both formal statutory powers assigned to him ex officio, but also being (one of) the Covid minister’s chief advisers).

It wasn’t even as if this was a single lapse, since Bloomfield acknowledged that he had last year several times accepted tickets to rugby games, and yet the Rugby Union had been negotiating with the government re the ability to host foreign teams in New Zealand.

New Zealand has tended to pride itself over many years about the incorruptibility of public life. Unfortunately, we have seen too many cases over the last few decades that suggest this is more folk myth than reality, although clearly there are many places worse than us. But “many places worse than us” is simply not an acceptable standard; rather it expresses a degree of complacency that allows standards to keep slipping a little more each time, with excuses being made (“not really that big a deal”), especially for those who happen to be in favour at the time. But those sorts of cases, those sorts of people, are precisely where a fuss should be made, where mistakes or rule breaches should not be treated lightly.

Integrity – and perceived integrity and incorruptibility – really matter at the top, and if there is one set of accommodations for those at the top, and another (more demanding) standard for those at the bottom it simply feeds cynicism about the political system and about our society.

What I worry about was captured quite well in a recent article in the Financial Times headed “British politics is morphing from delusion into sleaze”. Britain used to be highly regarded on this score too, but (sadly) no longer. Things seems worse there than here, but “many places worse than us” isn’t the standard we should tolerate.

I really don’t understand the near-deification of Ashley Bloomfield in some circles. Perhaps it is because I have not watched a single one of those 1pm press conferences. The man is a highly-paid very powerful senior public servant who, in the course of his stewardship at the Ministry of Health. seems to have done some things well and quite a few things not that well. But my indifference to the “cult of St Ashley” is really neither here nor there.

A senior public servant could have, so to speak, walked on water, and it would still have been a staggering misjudgement to have been accepting hospitality from an organisation that wanted to lobby him/her. Even more so, when it was not just a single lapse.

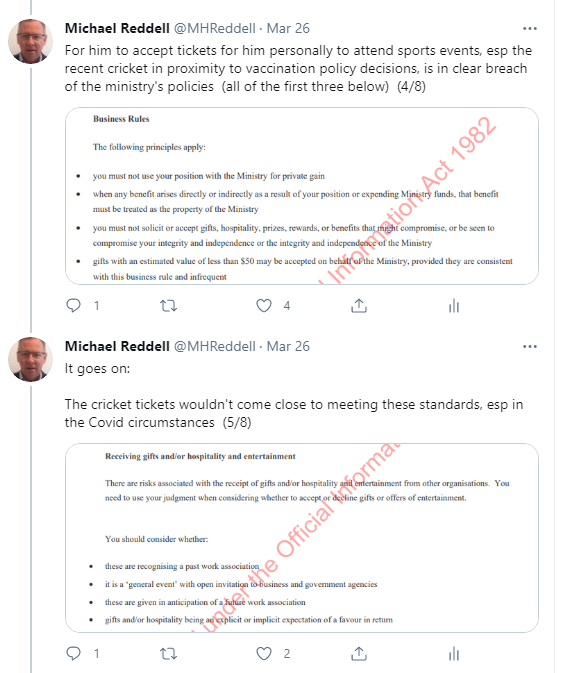

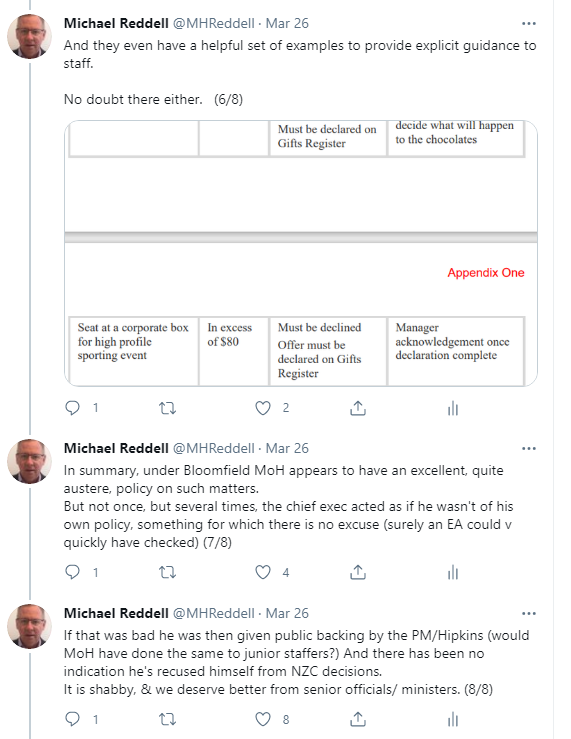

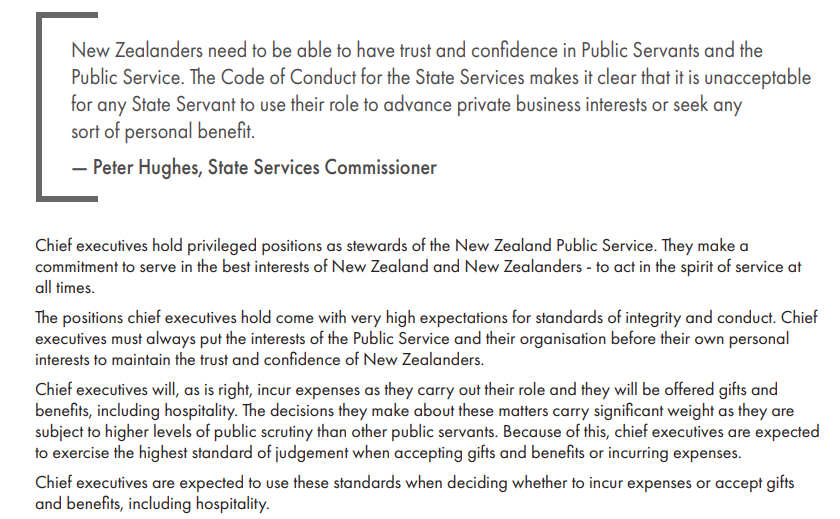

When the story first broke, I lodged OIA requests with both the Ministry of Health and the Public Service Commission (former SSC) asking for copies of their policies on acceptance of gifts and hospitality. The Ministry of Health responded quite quickly and I wrote about their response in a thread of Twitter. Rather than go through all the material again, here is a copy of the thread I posted.

Good policy, simply ignored by the chief executive (Bloomfield). It wasn’t as if this was the sort of decision he’d had to make under extreme pressure or on the spur of the moment. If he wasn’t aware of his own agency’s policy – which would be pretty extraordinary – no doubt he has not just an EA but a whole office, any one of whom could have been asked to check the policy and get back to Bloomfield.

He could have checked with his senior colleagues whether taking this hospitality was likely to pass the smell test. If he was still in doubt, he could have checked with his employer, Peter Hughes, the Public Service Commissioner. It appears he did none of these things, until after the story broke. From someone who has huge powers vested in them, it is not just a lapse of propriety but a stunning lack of judgement. If this is how things we come to hear about are dealt with, how much confidence can we have re other matters the Director-General is responsible for?

One hears suggestions that, Bloomfield having eventually realised it hadn’t been appropriate, all was made good by the fact that Bloomfield wrote a cheque for the equivalent of the cost of the tickets and donated it to the City Mission or some other worthy charity. In fact, that is almost pure distraction, since the money was never the main issue – on his salary he’d not have had any problems going to the cricket or rugby at his own expense if he’d wanted it (as many thousands of others did).

Writing a small cheque simply doesn’t adequately deal with the inappropriate behaviour in the first place – any more than it likely would have were it to have been someone well down the public sector food chain.

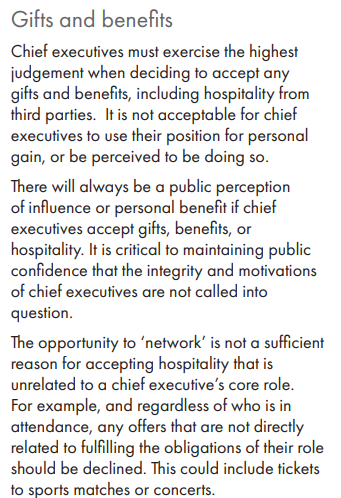

Anyway, that was the Ministry of Health response. On Friday, the Public Service Commission finally responded to my request. They provided me with the PSC’s own policies, for their staff and management, and a link to the guidance the PSC provides to public sector chief executives on such matters. I thought they were both pretty good documents.

The guidance to chief executives (of whom Bloomfield is one) is most relevant. This from the first page was just the sort of thing one would hope to see.

And this was pretty good to.

Did Bloomfield never read it?

And, slightly off topic, I was quite impressed with the austerity of this section of the guidance.

In some respects, the PSC’s own policies for their staff – not binding on Bloomfield – are even better.

Good stuff. The SSC policy even extends to immediate family.

Stringent rules, and aptly so.

So the Ministry of Health has stringent policies, the SSC has stringent policies, and the SSC guidance to chief executives is also stringent. Not one of those sets of policies should have led any employee – no matter how junior, or senior – to think that accepting sporting hospitality from entities trying to influence (“persuade, convince, explain”) the public servant would be anything close to appropriate.

Such offers should have been declined immediately and repeatedly. And not necessarily because Bloomfield’s advice or decisions would have been influenced by hospitality – though as he is human too, who (including himself) can really know – but because it is simply a dreadful look, that corrodes reasonable public expectations around the integrity of the public service, all the more so in this time of Covid when the state has been wielding more extensive than usual powers, and then (somewhat inevitably) exercising discretion around exceptions to the rules.

But what actually happened? We might deduce from Bloomfield’s later comments that the Public Service Commissioner had told him his conduct in these matters had not been acceptable. But we are left to guess even at that. Perhaps defenders of Bloomfield might cite personal privacy, but when you are a very high official and you overstep the bounds in public, any rebuke also needs to be clearly visible to the public. Otherwise, we might reasonably think one of the public sector elite was looking after another of that same elite, perhaps even playing politics.

Because the political “leadership” was far worse. We – the public can’t do anything about Peter Hughes or Bloomfield – but we rely on the politicians we elect to demand high standards from the public service. And what happened in this case? Both the Prime Minister and the Covid minister did little more than laugh off these breaches, suggesting that no one begrudged Bloomfield an afternoon at the cricket after all his work. Pure distraction, pure minimisation, when the issue was never about him having a Sunday afternoon off at the cricket, but about who hosted him, and what interests his host had in influencing him.

I don’t think accepting one invitation to a sports event should be a firing offence – even for someone as powerful and prominent as the Director-General of Health. Repeat offences, as we saw in this case, do raise the ante somewhat, because they create doubts about the man’s judgement, and even about a possible sense of entitlement. David Clark lost his position as Minister of Health for offences that, in the scheme of things, were less serious, albeit embarrassing to the government.

But we should have been able to expect the Public Service Commissioner, the Prime Minister, and the Covid minister (for that matter the Minister of Health) to all have made it crystal clear, in public, that Bloomfield’s behaviour represented a serious and repeated lapse of judgement, a breach of the clear standards expected of MoH staff and public service chief executives, and that any repetition of this sort of lapse would be utterly unacceptable.

Or are the rules only for (a) show, and (b) little people?

Please share so others can discover The BFD.