Don Cockrill

Maritime Pilotage Consultant.

Speculation as to the cause of the now infamous Suez Canal grounding of Ever Given is inappropriate and unproductive. However, amongst all the media hype and sometimes less than well-informed comment there is a lack of background fact. It is worth putting the scale of the navigational challenges of ULCCs transiting the canal into some sort of understandable context.

The canal was deepened about 12 years ago to accommodate revised Suezmax vessel limits which are based on a ratio of beam to draft. Maximum beam being 77.5 metres at a draft of 12.2 metres and 20m draft at 50 m beam. Ever Given thus falls well within these criteria at 59 m beam and 15.7 m draft.

The Suez canal authority consider 400m length the general maximum for a vessel transiting the canal although longer vessels may be granted special consideration.

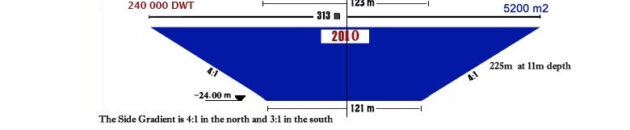

The canal width is of particular relevance for this incidence. At its surface the canal is about 313 m wide, however, its construction profile means that the sloping sides give a width of about 225m at 11 metres draft, decreasing to about 121 m bottom width. Thus at 400m, such ships are significantly longer than the navigable width of the canal waterway.

The usual transit speed for a ship in the canal and indeed any canal is about 8 knots. A combination of factors dictates this, predominantly the hydrodynamic effects of water displacement as the ship moves along the canal and the resulting huge pressure forces that are generated.

In simple terms, relatively slow speeds are required combined with maintaining a central track within the canal cross-section in order to minimise and maintain a balance of the hydrodynamic forces acting on the sides and bottom of the hull.

However, in addition there are the effects of wind and tidal currents to consider. The estimated lateral surface area of a loaded ULCC such as Ever Given is about 16,000 sqm. A 30-kt. wind such as that which has been reported at the time of the grounding if on the beam will generate a force on the ship side of about 300 mt. Additionally, there is the tidal current to consider. Although minimal compared to other parts of the world, there is nonetheless a tidal cycle and associated water flow. Even a low current of 0.5 knot will impart a force on a ULCC at a similar draft of 75mt.

Acting in unison, a combined external lateral force on the vessel of about 375 tons (possibly more) is conceivable under the worst conditions. More than enough to cause a deviation from the very specific track that the transit demands.

Once any deviation from the intended track occurs then an imbalance of hydrodynamic forces simply adds to the problem and thus creates a huge challenge for correcting the vessel’s course and resuming the track. It is debatable what effect applied rudder and engine power alone would have under these circumstances.

Navigating over-size vessels in restricted waterways is nothing new and even the ULCC has become ubiquitous in many ports where they are navigated and manoeuvred in waterways designed for much smaller vessels. In many waterways dynamic escort towage – that is the use of a tug made fast aft and which is utilised to assist very effectively in both speed and directional control of the vessel is commonplace. Media reports to date suggest that one was not in use on this occasion.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.