Daniel Goldwater

Chef CMRJ

Jerusalem

Israel

Israel has a problem (that’s an understatement): wherever you throw a stone, wherever you spit or poke around in the dirt a little you might find something interesting.

Israel has been populated by many different peoples over so many centuries so everything is there right under your feet. Scratch a little, dig in an organised and methodical fashion and you are sure to bring up someone’s past.

That someone may have been a cave-dwelling Neanderthal minding his own business, an ancient civilisation or a more recent time in ancient history. Interestingly, most if not all significant construction in the Holy Land ceased at the zenith of the Ottoman Caliphate, who happened to be the last great conquerors and rulers of this land.

The Ottomans were archeologically the last of the great builders in the Holy Land before the Jewish return ramped up in the nineteenth century and the brief three-decade British honeymoon with Palestine in the first half of the twentieth.

Take a wander along a white sandy beach on the eastern Mediterranean seashore. If you can get your mind past the filth and plastic flotsam and jetsam, you may find yourself walking on pottery shards from forever and small pieces of Roman Carrera marble smoothed by millennia in the wash of tides. Look keenly enough and you could just discover something special to take home with you and put on the mantelpiece.

Archaeology sadly has reluctantly become a part of that Orwellian maxim bandied about by everyone about everything. “Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past”. Archaeology, it would appear, is much more important than most of us suppose.

The politicisation of UNESCO by Israel’s detractors encouraged by the Palestinian National Movements and their backers is having apparent success at the usual United Nations forums, but can these multilateral campaigns really change history and archaeology?

It should be noted that once historians and archaeologists allow their disciplines to be politicised and start tinkering with evidence and empirical data to accommodate the fashion of the day, they will become the props of narrative only and their scholarly world will be damaged beyond repair.

Aside from modern day Israel and its seemingly shambolic and frenetic being, all that exists in this ancient land is an almost infinite layering of the ‘past’. This rich tapestry is inclusive of many, but unless your bones, monuments and relics can be found, identified, verified and catalogued you simply never were.

In modern-day Israel there are your obvious go-to ‘digs’ where the characters of the Bibles appeared, where kings and queens paraded and spectacular events and miracles apparently took place. Today, however, most of the new discoveries are found through mundane road widening and general construction as cities and towns expand and renew themselves.

These ‘bonus’ rescue digs have led to the revelation of many previously unknown archaeological jewels, mostly mosaic floors of Byzantine churches, ritual baths and synagogues, mosques and settlements from early Islamic periods along with parts of old Roman roads and so on.

In Israel everything old of interest or value that is dug up, or accidentally discovered by anyone, belongs to the state by law. To that end there is a government Department of Antiquities that has an army of archaeologists and eager volunteers available to be rushed in to do “rescue digs” and ensure that all of the past is at least recorded and saved for future study and posterity; kept in their storerooms and not on your mantelpiece.

I have been blessed by two very lucky and exciting encounters with this past. The first was in the early nineties when we renovated our ground floor apartment in Rehavia, Jerusalem, and the second while wandering a beach near Herod’s Caesarea after a major storm.

While excavating our apartment in Jerusalem we fell through the ceiling of a previously undisturbed Byzantine era family tomb, complete with human remains and archaeological artefacts. We notified the authorities, who sent a team of archaeologists. They quickly did their thing and left us with an empty tomb and a lot of expensive structural work to compensate for the newly discovered cavity under the building’s foundations.

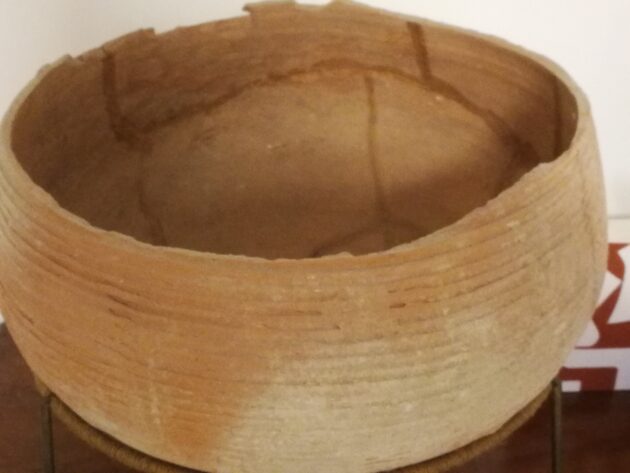

My second great find was on the coast to the south of the remains of Herod’s coastal aqueduct that fed Caesarea. While walking on the beach with my wife and dog we glimpsed the outline of an upturned clay vessel in a dune that had been recently eroded by a storm. As I cleared the sand away from around the vessel it became apparent that it was whole and upside down, but also clearly fractured into mostly large pieces. We gently removed all the pieces, took it home and my wife painstakingly reconstructed it and glued it together.

During the same period, we also found a decent chunk of mosaic flooring that had been exposed by the elements, which was also put back together by my wife. Both of these are from the Byzantine Christian period.

When walking in History be careful not to spit; you never know what you may find.