The Labour Day holiday of 2020 prompts thoughts about what lies in store for our country’s immediate future following the landslide electoral success of a Labour government. What are the implications for Kiwis as they contemplate the likely consequences of three more years of social, economic and political tinkering under a Labour Party composed so significantly of newcomers to the reins of power?

For the incoming Labour government, it will have to be tinkering, if they hope to retain the support of the multitude of centre-rightists and some out-rightists who sidled leftward a couple of weeks ago. Concession to any appreciable degree to the daydreams of the Greens, unions and other extreme leftists, will cost Labour, as has already been tacitly acknowledged by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. How far Labour is prepared to go will become obvious within days when we are told what part (if any) the Greens will play in the new government, and how Ms Ardern allocates portfolios to those Labour MPs elected to cabinet by her caucus (and I look at that in some detail later).

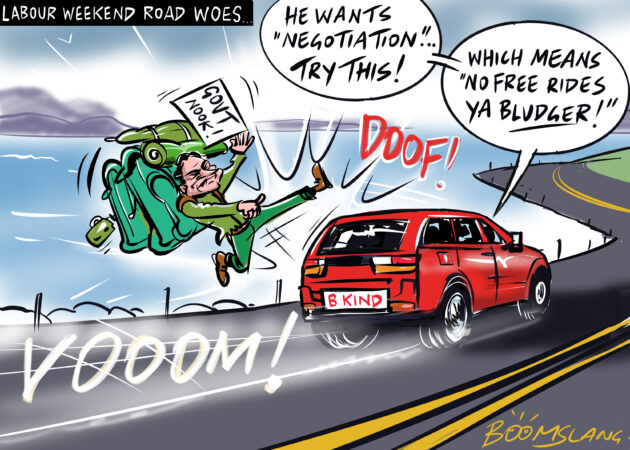

The BFD. Cartoon credit BoomSlang

The principal opposition party, National, is in labour – as in the pains that must inevitably precede its re-birth. Revolutionary re-birth is as urgent for National as it is essential. And it has to be revolutionary, not just to reverse the slide in voting support the party has suffered, but also to adjust to the new realities of a post-Covid pandemic world. National has no time to waste, which will inject spice into the party’s annual general meeting in Wellington on 21 November, at which I will be a voting delegate for the Papakura electorate of Leader Judith Collins.

The National Party must spend little time flicking among the entrails of defeat, and focus on re-organisation – of the party organisation. What is needed is to restore power to the party membership in a way that does no damage to the effectiveness of its parliamentary caucus, but rather adds strength and purpose to caucus as it holds the Labour government to account as strongly as “Crusher” Collins has already promised.

To those of us who regard ourselves as National Party “insiders”, it was the organisation that let us and caucus down – not the other way round. We were out-spent and out-campaigned by a resurgent Labour Party organisation to a degree unparalleled in my 60 years of involvement. Yes, it is an advantage to have the resources of the Government and its agencies behind you when campaigning for re-election, and the COVID-19 pandemic was a communications windfall for Prime Minister Ardern — who played that advantage with Goebbels-like skill in her repetitions that we had been saved by “going hard and early” and ensured penetration of that message by her $50 million payout to news media, on top of what Labour spent on paid advertising.

The BFD. Photoshopped image credit Luke

But I am distressed to have to say that the 2020 campaign was easily the worst by National in the last 60 years, and for that, it is the organisation, not the caucus, that is responsible, and that’s where change and improvement are both essential and urgent.

It is clear now, with the clarity of hindsight, that the corporate structure, centralised in Wellington, introduced following the Steven Joyce-led review after the 2002 debacle, well though it functioned in the lead-up to the 2008 return to power under John Key, was no longer appropriate to the circumstances of 2020; even less so for what will be the “new world” post-Covid. Personal influence, and its resultant power and policy innovation, slipped too far from the grasp of the rank-and-file electorate membership towards the caucus room, increasingly dominated by whatever numbers the polls yielded, with short term pragmatism taking precedence over vision and principle.

In my earliest years attending National Party conferences, at divisional (regional) and national levels, then Prime Minister Keith Holyoake used to remind his ministers and MPs that the conferences belonged to the delegates. As a result, delegates talked and MPs listened, and the highlights were always lively debate on remits. These days, there are few remits discussed, and anything remotely controversial doesn’t even reach the agenda; the stage is dominated by ministers (or, in opposition, shadow ministers) who talk while delegates listen.

That needs to stop, and the AGM on 21 November would be a great place and time to start, if only to signal to the party itself and its supporters that the process of essential change and re-organisation has already begun. As the people who select parliamentary candidates and finance their election campaigns, rank-and-file National Party members need to reclaim ownership of their party, bring its processes up to what is required for the post-Covid world and elect to the leadership of their party organisation people able and willing to restore the mass membership enthusiasm and voting support National needs to return to government in 2023.

As for the parliamentary caucus, I fully and confidently expect Judith Collins to achieve her undisguised ambition to be Prime Minister. But for Covid, Judith would now be Prime Minister-elect, if the National Party caucus had had the gumption to elect her to replace Bill English when he resigned in 2018. With Judith as leader and Simon Bridges as deputy, National would have had, and be seen to have, not only strong leadership but also a credible succession plan. But the National caucus of 2018 lacked both foresight and gumption and turned to Judith only after its short-sighted reactions to media-fuelled antipathy to Bridges, and the ineptitude of those silly enough to back Todd Muller.

So Judith was handed the Covid-tainted poison chalice. The only advice I will give to my friend Judith is to repossess her brand as “Crusher”, and focus it on what will be a brittle Labour administration. And not just hold Labour to account, but also to expose failures such as the man-made global warming hoax (now called “climate change” in the absence of said warming) and defaults in house-building, poverty alleviation and the scourge of shoddy construction that continues unabated.

Composition of the new Labour cabinet will be interesting, with Ms Ardern restricted to deciding who gets what portfolio. One assumes no one in the Labour Caucus will be game enough to cross its now strong Maori component, which will mean the retention of Kelvin Davis as deputy leader, and thus, Deputy Prime Minister. My guess is that there will be no ministerial posts for the Greens, inside or outside cabinet, which would mean a new Minister for Climate Change Issues. I assume Kiri Allan, who captured from National the quintessentially provincial rural/urban seat of East Coast, will be a popular caucus choice for election to Cabinet. Given the adverse economic effects of ETS and other anti-farmer measures piloted by former minister James Shaw, I wonder whether Ms Ardern would be tempted to pass this portfolio to Ms Allan, along with regional Issues, to signal the rural community that there will be reduction in the planned persecution of farmers.

The unveiling of the new Labour executive will be a significant signal of what we can expect for the next three years.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.