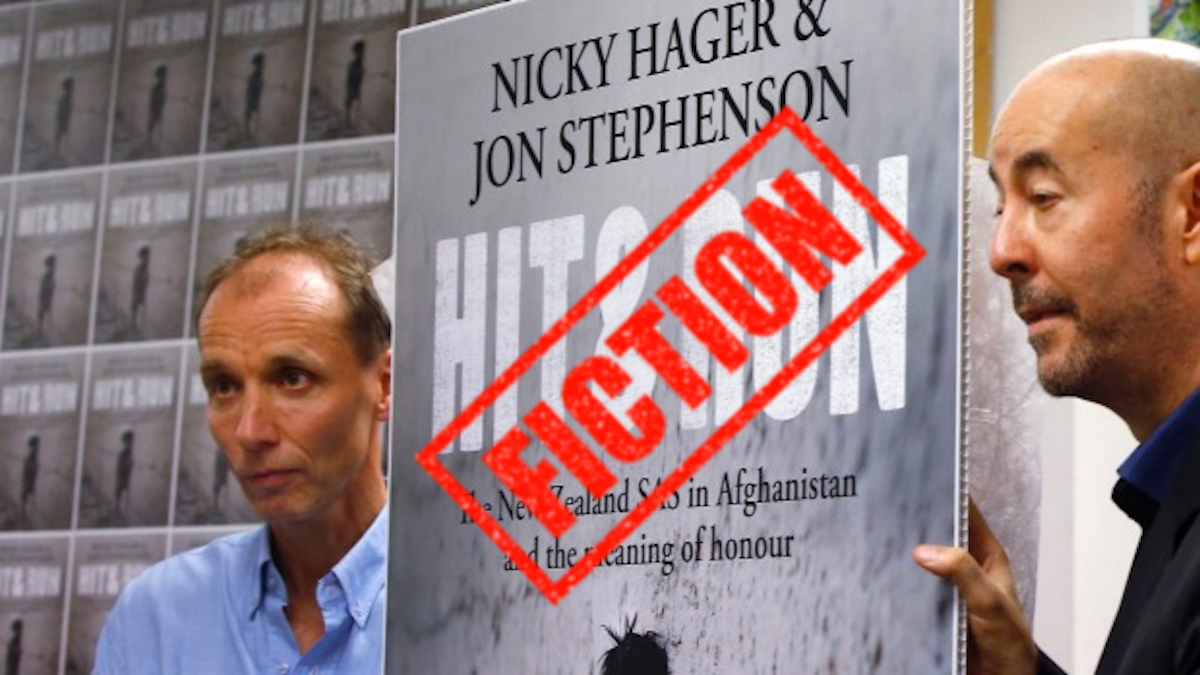

The Operation Burnham Inquiry results were released last Friday. You’d never have known, from the media reports and the crowing of so-called journalist Nicky Hager, that the report actually didn’t vindicate him.

What the media and Hager failed to acknowledge was that the Inquiry found that the central basis of the book, that the NZSAS personnel involved in the operation killed a 3 year old girl called Fatima extra-judicially and against the Geneva Convention, was actually a lie.

The attack made in the book was in fact a shabby and deliberate falsehood defaming the integrity of our soldiers.

That may sound strongly worded, and you may say that I have an axe to grind against Nicky Hager.

And you’d be right, but the Inquiry didn’t. It was authored by Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Sir Terence Arnold, both with unimpeachable credentials.

On page 122 of the report and for the next four pages they outline all the deceit of authors Jon Stephenson and Nicky Hager. I apologise for the length of the excerpt, but I think it is important for you to read it all in the context it was given.

[47] We had hoped to find objective evidence that would help to establish whether civilian casualties resulted from Operation Burnham. With the assistance of Mr Stephenson, we obtained the photographs used in Hit & Run of some of those said to have been killed or injured in the operation and asked two independent experts to take the metadata from them to see what, if anything, that metadata might tell us. The independent experts undertook their analysis separately, not knowing what the other had concluded. In the event, their conclusions were largely the same.

[48] We submitted the image of Fatima at page 52 of Hit & Run together with three other photographs said to be of her to our independent experts for their (separate) analysis. Both said that the photographs were taken on a Samsung GT-S7562 mobile phone on 30 October 2016 and 8 December 2016. The Samsung GT-S7562 was not introduced to the market until September 2012.

[49] Images of Islamuddin, obtained from Mr Stephenson, were also submitted to our experts for analysis. The metadata from those indicates that they were taken on a Samsung GT-S7562 mobile phone on 8 December 2016, although another date, 1 January 2011, has been added to the metadata, apparently as a result of files being edited with Nokia Image Editor 2.7.4. One expert concluded that there were contradictory indications in the metadata as to whether some of the photographs of Islamuddin were photographs of photographs. As it transpired, however, the possibility that they were photographs of photographs was not something we had to resolve, for reasons we explain when we discuss the evidence in relation to Islamuddin’s death.

[50] At page 73 of Hit & Run, there is a photograph which, according to its caption, shows a boy named Abdullah, identified as Fatima’s brother, being treated on the day after the operation for wounds caused during the operation. The person treating him is identified in the caption (incorrectly) as Dr Abdul Rahman. That and other similar photographs were supplied to Mr Stephenson by Dr Rahman together with a video showing the boy’s wounds being dressed, and Mr Stephenson has made them available to the Inquiry.

[51] The metadata from the photographs of Abdullah indicated that they were taken in 2012 on a Nokia C5-03 cell phone, a model which was not introduced to the market until December 2010. There is no metadata associated with the video (which does not appear to be the source of the still images), but it must have been taken at the same time as the photographs. Obviously, if the metadata associated with the photographs is accurate, the photographs and the video could not be a record of events on 22–24 August 2010, immediately following the operation.

[52] We enquired of our experts whether the photographs and the video could have been taken originally on another phone and then transferred to the Nokia at a later stage. The advice we received was that transferring them in that way would not change the metadata to show the photographs to have been taken at a later date than they actually were. Rather, the metadata would travel with the images (unless deliberately stripped or modified for some reason).

[53] We also enquired whether the still images could be photographs of photographs taken earlier on another device. We were advised that while some images in the book may be photographs of photographs (such as the image of Islamuddin on page 57), there were several features of the photographs of Abdullah that made that highly improbable. In particular, the Gain Control and the LightValue metadata figures were consistent with the images being originals. Further, this would not explain the video, which appears to have been taken at the same time.

[54] We note in passing that there are issues with other images from Hit & Run. We give four examples:

(a) Page 74 of the book has a photograph said to be of Noor Ahmad, who is described as a boy from Khak Khuday Dad, receiving hospital treatment after the raid. That photograph was taken on a Samsung GT-19082 cell phone in 2015. Mr Stephenson has acknowledged that the photograph is not relevant to Operation Burnham and should not have been included in the book.

(b) Page 73 of the book has a photograph of a grave, which the caption says was erected for one of the victims of Operation Burnham and is a place of prayer where people come to make wishes. The photograph was provided to Mr Stephenson by Dr Rahman, with a document saying that the gravesite was in Naik. The metadata from that photograph indicates that it was taken on a Nokia C5-03 cell phone in 2012, like the photographs of Abdullah. This grave is not in Naik (or Khak Khuday Dad), however. Rather, the geolocation data from the photograph shows that the grave is located close to Pol-e Khomri. Pol-e Khomri is 100 kilometres from Tirgiran Valley as the crow flies. A high-voltage power pylon can be seen in the background behind the grave, which further confirms that the photograph was not taken at Naik. Commercially available satellite imagery does not show any power pylons in the vicinity of Naik at that time. Current satellite images of the location indicated in the geolocation data match the topography in the photograph and show high-voltage pylons.

(c) The photograph at page 53 of Hit & Run is not, contrary to the caption, a photograph of houses as they were at the time of Operation Burnham. Rather, the house on the right of the photograph is A3, where Mohammad Iqbal and his sons, Maulawi Neimatullah and Abdul Qayoom, lived. The house on the left of the photograph was built some years later, after October 2014, as satellite imagery confirms. As we understand it, the authors accept this.

(d) Photographs identified as being of different houses in different villages are in fact photographs of the same house. So, for example, the photograph identified at the top of page 131 of Hit & Run as being of Abdul Faqir’s house in Khak Khuday Dad and the photograph of Mullah Rahimullah’s house in Naik at the bottom of page 132 are in fact photographs of the same house. As we understand it, the authors accept this also.

[55] In the result, the analysis of the photographic material in the book and that supplied to us by Mr Stephenson left us with three relevant concerns. The first concern is that the photographs, particularly those provided to Mr Stephenson by Dr Rahman, raise sufficient issues concerning the accuracy of dates and locations that they have little or no corroborating value.

[56] The second concern is that the metadata relating to the photographs and video showing Abdullah receiving treatment, and the photographs of Fatima, raise considerable doubt about the reliability of statements made by the parents of Abdullah and Fatima about what happened during Operation Burnham, as we now explain.

[57] The parents of Abdullah and Fatima, Abdul Khaliq and Khadija, were interviewed by Mr Stephenson and Ms Paula Penfold of Stuff in 2017. In addition, Mr Stephenson conducted an interview with another person who had knowledge of the relevant events in 2015 and provided us with a transcript of the interview. Further, the lawyers in Kabul assisting the Inquiry obtained comments from Abdul Khaliq, Khadija and Abdullah on a number of matters.

[58] This material shows some inconsistencies—in the varying descriptions of Abdullah’s injuries, for example—but we do not regard these as being significant in terms of assessing reliability. Rather, we see them as the type of inconsistency expected when people are asked to recall traumatic events of some years ago, in a setting that is foreign to them.

[59] That said, some matters do raise serious questions about reliability. As we have explained, the metadata from photographs of Abdullah’s head wound being treated indicate that they were taken in 2012, not 2010, and we have been unable to find any technical explanation for this discrepancy. Abdullah indicated that the photograph from Hit & Run is not of him, but it is clear from a scar above his left eye and a mole on his forehead that it is. Further, Mr Stephenson conducted an interview with a villager who was present on the night of Operation Burnham and who would, given their relationship, have been expected to mention Fatima as one of those present and killed, but did not (although mentioning others). Even making allowance for the passage of time and the traumatic nature of the events in question, the omission is difficult to explain if Fatima was there and was killed.

[60] Additionally, during their Stuff interview Abdul Khaliq and Khadija were shown the photograph on page 52 of Hit & Run and identified it as a photograph of their daughter Fatima. As already noted, we have been provided with that and other photographs of Fatima, and the metadata from them indicates that they were taken in September and December 2016, rather than at some time before 22 August 2010 when the operation occurred. Again, we have been unable to find a technical explanation for this discrepancy. When this was raised with Abdul Khaliq and Khadija, they reiterated that the photos were of their young daughter, Fatima.

[61] The discrepancy in the metadata does not, of course, prove that a child was not killed during Operation Burnham. Rather, it simply indicates that it is unlikely that the child in the photograph was killed.

[62] In this context, we note that other villagers were shown the photographs said to be of Fatima. They gave mixed responses. Some said they did not recognise the child; others went further and stated that the child was not Fatima. One Afghan local from outside the villages stated that it was Fatima, but only knew this because her parents had previously shown the person the same photograph.

[63] It is also relevant to note that, in the Stuff interview, Abdul Khaliq claimed that his house was so severely damaged that “not even a scarf” remained. This is inconsistent with other evidence, discussed below, which indicates that A1 and A3 were the only buildings to suffer significant damage as a result of the operation.

[64] The third and final concern is that much of the information Mr Stephenson obtained about civilian casualties during Operation Burnham came from Dr Rahman. Dr Rahman said that he had gone to Tirgiran Valley immediately after Operation Burnham to provide medical assistance. There is some support for this in a brief incident report compiled by the AIHRC on 28 August 2010, which noted that a medical team had been sent to the area, and from villagers who say that Dr Rahman provided medical assistance after the operation. Despite this, there is a question as to Dr Rahman’s reliability given the information derived from the metadata of the photographs that he supplied to Mr Stephenson. We also note that contemporaneous intelligence reporting indicated that Dr Rahman had links to the Taliban, although it did not confirm he was himself a Taliban member. Indeed, according to some accounts, he was ultimately killed by the Taliban.

[65] There is an additional point raised by the photographs in Hit & Run which we should address for completeness. The book says that the villagers found two empty plastic drink bottles (described in the book as “strange” drink bottles) at a lookout point on the top of the ridge that indicated the location of the overwatch position, and that the bodies of Islamuddin and Abdul Qayoom were found nearby. The book includes a photograph of two empty drink bottles alongside some empty shell casings, with a caption that implies that these objects were found at the overwatch position (although this is not stated expressly). NZDF said in a presentation to ministers in 2018 that the book claimed this equipment was used by the NZSAS during the operation and rejected that, showing different equipment it said was in fact used by the NZSAS.

[66] Having reviewed the source information provided to Mr Stephenson, it appears there has been some confusion over the significance of this photograph. The photograph does not depict the drink bottles the villagers say they found at the overwatch position. The image was taken some time after the operation to show some shell casings that Dr Rahman said were found after the operation at a high point on the ridge. The drink bottles appear to have been included in the photograph to show the relative size of the casings—not because they were said to be of any direct relevance. The bottles pictured were of a kind which appears to be commonly used in rural Afghanistan. The code on the casings show they are 30mm rounds from the Apaches, as the book states elsewhere. They are not from ammunition used by the marksmen.

[67] While the placement and captioning of the photograph in the book has led to some confusion, we are satisfied this can be disregarded when assessing the villagers’ description of where the bodies of Islamuddin and Abdul Qayoom were found. One of the villagers interviewed by lawyers in Kabul said that empty mineral water bottles were found near Abdul Qayoom’s body. Some of those at the overwatch position were carrying small plastic water bottles in addition to their NZDF-issue canteens. Given this, there may well have been empty mineral water bottles at or near the overwatch position. Further, as we discuss below, it appears that Abdul Qayoom was the man shot by a marksman at the overwatch position and the villagers’ description of where they found his body appears to be broadly accurate.

So, to summarise:

- Operation Burnham occured in Afghanistan’s Tirgiran Valley on 21–22 October 2010.

- The photographic evidence provided in the book was analysed by two independent experts. The independent experts undertook their analysis separately, each not knowing what the other had found or concluded.

- The photographs of Fatima were taken on a Samsung GT-S7562 mobile phone on 30 October 2016 and 8 December 2016, six years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- That version of cellphone was not available in the market until September 2012, Two years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- For the images of Islamuddin metadata from those indicates that they were taken on a Samsung GT-S7562 mobile phone on 8 December 2016, although another date, 1 January 2011, has been added to the metadata: six years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- The metadata from the photographs of Abdullah (page 73) indicated that they were taken in 2012 (two years AFTER Operation Burnham) on a Nokia C5-03 cell phone, a model which was not introduced to the market until December 2010, two months AFTER Operation Burnham.

- The video of medical treatment claimed to be in the aftermath of Operation Burnham was consistent with the photographs of Abdullah taken two years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- Page 74 of the book has a photograph said to be of Noor Ahmad, who is described as a boy from Khak Khuday Dad, receiving hospital treatment after the raid. That photograph was taken on a Samsung GT-19082 cell phone in 2015, five years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- Page 73 of the book has a photograph of a grave, which the caption says was erected for one of the victims of Operation Burnham and is a place of prayer where people come to make wishes.

- The metadata from that photograph indicates that it was taken on a Nokia C5-03 cell phone in 2012, two years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- The grave is not in Naik (or Khak Khuday Dad) as claimed by the authors.

- The geolocation data from the photograph shows that the grave is located close to Pol-e Khomri. Pol-e Khomri is 100 kilometres from Tirgiran Valley as the crow flies.

- There are photos of houses on page 54 of ‘Hit and Run’.

- One house pictured was built after 2014, four years AFTER Operation Burnham.

- Photographs identified as being of different houses in different villages are in fact photographs of the same house.

- There is no technical explanation that disproves the metadata.

- Dr Rahman was a Taliban sympathiser who was later killed and therefore cannot be interviewed.

- All of the photographic and video evidence supplied by Dr Rahman has been proven to have been taken AFTER Operation Burnham.

- Stuff’s Paula Penfold’s interviews of people, particularly the parent of Abdullah and Fatima were also inconsistent with metadata

In other words, all the claims made about photos were wholly false. A multitude of lies, designed to fabricate a false narrative that the NZSAS were child killers and acting out of revenge.

The Inquiry report, far from vindicating the authors, in fact proves they are liars.

Nicky Hager claims, as do others, that he is an investigative reporter who thoroughly researches his stories.

We now know that anyone relying on evidence supplied by Nicky Hager is likely to have been sold a fraud.

The Inquiry report is actually damning of the evidence supplied by Hager and Stephenson. I bet Jon Stephenson is wishing he never went near Nicky Hager. Stephenson at least gets dust and dirt on his clothes from war zones. The closest Nicky Hager gets to a war zone is when he is fabricating war stories from Afghanistan.

Almost every aspect of the photographic and video evidence was false, and therefore the basic premise of the book is also false.

If these two so-called journalists are prepared to mislead and deceive on such a grand scale it makes you wonder what else they have claimed in the past that is also false.

Images: