After Cook’s last trip (1777), there are no more foreign visitors to New Zealand for some time. The fierce reputation of the Maori has spread and put off tourists (especially the people-eating part); and the major exploring nations of the world at this time (Britain, France, Spain), have other things to do.

Britain has Europe, North America and India to worry about, and doesn’t need any more new colonies. It’s only after they decide to put a penal settlement in Australia (1788), that the attention of the outside world begins to trickle back to New Zealand. But only just trickle back.

The historical development of New Zealand is not simple and organised. It’s complicated and disorganised. Compared to New Zealand, the development of Australia, Canada and the United States is straightforward. Orderly even. New Zealand is not orderly at all. It proceeds in fits and starts. Wars on and off, government off and on, and always there somewhere the constant presence of the Maori, a wild people in a wild land.

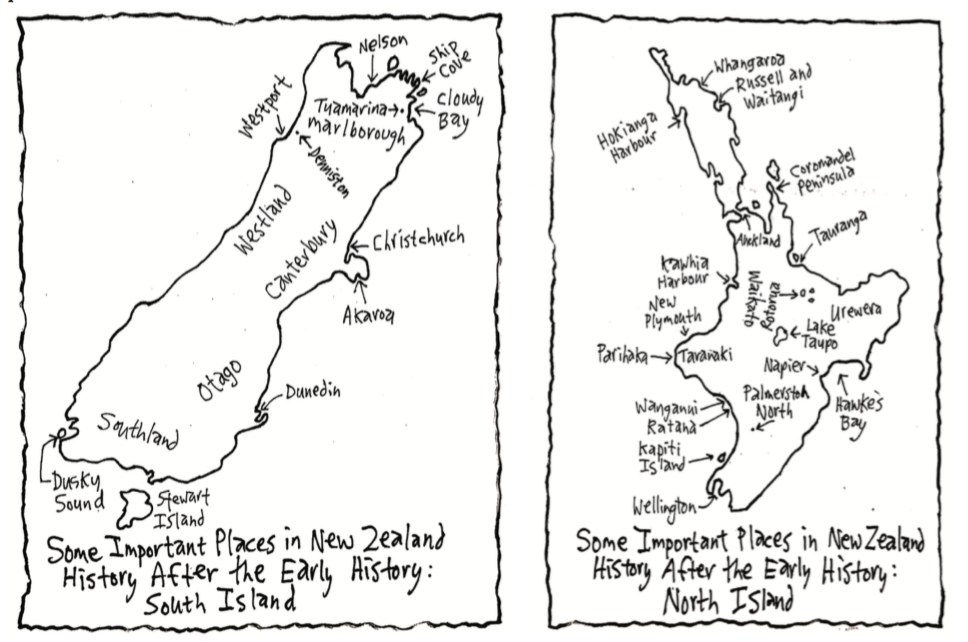

George Vancouver (who had been with Cook), sails into Dusky Sound, South Island; and William Broughton finds the Chatham Islands (1791). Then the sealers, whalers and traders arrive. New Zealand has new stocks of seals and whales that nobody has ever hunted before, good harbours, lots of trees, and best of all, no laws, restrictions or authorities to worry about. New Zealand is the wild South Pacific.

A gang of sealers from Sydney are dropped in Dusky Sound in 1792 and picked up again in 1793 with 4,500 seal skins; leaving behind a half-finished boat they had been building just in case they were forgotten about.

The French (d’Entrecasteaux) and the Spanish (Malaspina) call in at New Zealand in 1793, but it’s the British with their base in Australia that have the upper hand in New Zealand. Sealers go to Dusky Sound, Doubtful Sound and Riverton. Whalers go to The Bay of Islands, Poverty Bay, Hawke’s Bay, Maketu, Taranaki, Kapiti Island, Tory Channel, the Banks Peninsula, Otakou, Waikouaiti, Preservation Inlet and Cloudy Bay (1792).

A ship from Sydney cuts timber for ships’ masts in the Hauraki Gulf (1794). Others cut timber and trade the Maori for flax at Thames and The Bay of Islands (1795). Two Maori chiefs are kidnapped and taken to Norfolk Island to teach convicts how to make cloth from flax. But only Maori women know how to make cloth from flax, so the two chiefs are returned to New Zealand (1793).

Another sealing ship arrives in Dusky Sound, but is wrecked and 244 people are stranded there (1795). They finish building the half-finished boat left there by the earlier group, and 209 of them escape in 1796. The rest are rescued in 1797 having started to build another boat just in case.

The first permanent white turnips to live in New Zealand are sealers and whalers that jump ship and go native. The first permanent white turnip settlement in New Zealand is Russell in The Bay of Islands. Here sealers and whalers repair ships, process sealskins and whale oil for shipment to Australia, and trade with the Maori.

The reaction of the Maori to these new arrivals shows their complicated nature. Some are hostile, but others aren’t. They see individuals and small numbers of new people as not being threatening to the tribe; while the larger groups coming and going all the time in big ships are too powerful to defeat over and over, but can also be useful to the tribe. The new people can be used. Friendliness is deceptive.

The Maori trade food, wood and flax for fish-hooks, axes, tools, rum, clothing, sugar and muskets. Especially muskets. Some Maori catch on very quickly to the advantage that guns have over clubs and spears, and they prefer guns. But rather than try to defeat the white turnips for them, they simply trade for them. They use the traders for what they can get from them to help them defeat their enemies. Other tribes.

The white turnips are not necessarily the enemy, but someone who can help them defeat the enemy. The Maori are tribal, it’s both their strength and their weakness. And this characteristic is one of the most important things that defines New Zealand history. It will continue from here until the end of the New Zealand Wars, 81 years later (1791-1872). It’s one of the main reasons New Zealand history is complicated. Because the Maori are a complicated people.

Russell is a wild place (“The Hell-Hole of the Pacific”, not a great slogan for tourism). There is no law and order. Who is to provide it? The Maori are in control. There are more of them and they have the goods the traders want. The Maori grow vegetables, raise pigs, cut down trees and make flax cloth and cord. They crew on ships and sail away to see the world (many of them want to go to Britain to see the King). Some of them get their own ship and go into business themselves. But there is still trouble.

The Boyd Massacre, Whangaroa, August 1810

A Whangaroa chief is flogged for signing up to work on the ship the “Boyd”, but then refusing to work (chiefs do not work). When the ship puts into Whangaroa and some of the crew go ashore, the chief has them killed. The Maori then dress up in the dead sailors’ clothes, board the ship, kill everybody except one woman and three children, plunder the ship, and set it on fire, accidentally blowing up 13 of themselves.

After a trader rescues the four white turnips, five whaling ships go into Whangaroa, burn down the Maori village, and kill many Maori. The chief who originally started the whole thing is actually killed by his own people for rescuing five sailors off the burning ship, who are later killed and eaten anyway.

Tokomaru Bay, East Cape, March 1816

An American trading ship puts into Tokomaru Bay and the Maori begin trading with it, while at the same time removing lead, nails and any metal bits they can take off the ship. When the ship tries to leave they kill three sailors, take the other 12 prisoner, and burn the ship. The next day they cook and eat six of the prisoners while the other six watch. These six are then tattooed and given out as slaves to members of the tribe. One of these is later made a chief, escapes (1826), and writes a book about his adventures (1830, John Rutherford).

The sealing (1820) and whaling (1850) eventually stop, but the trading goes on. And the planting of potatoes. The Maori want to trade for muskets. The Bay of Islands and Hokianga Harbour Maori are the first to get guns, and the first to recognize the importance in warfare of the potato.

Fighting and killing is a seasonal occupation. The Maori plant their crops in October/November, go to war, and then return to harvest in January/February. But the potato that Cook gave them could be planted earlier and required little attention in the field, meaning that they could get away to the fighting and killing earlier. And the potato was an excellent portable food to travel with. The musket and the potato gave them an advantage over their enemies. Just what they wanted.

The first recorded tribal fighting using guns is near Dargaville, Northland in 1807. A tribe with muskets from Kaikohe is all but wiped out by a tribe without muskets from Kaipara Harbour and Whangarei; because the tribe with muskets is caught by surprise by the tribe without muskets and has no time to load the muskets. The tribe without muskets then becomes the tribe with muskets; and the tribe with muskets becomes the tribe without muskets, and with hardly any tribe left either.

But some of them survive (including one named Hongi Hika), and they start trading for more muskets. They train and drill with the muskets, devise new war tactics for the muskets, get themselves a leader, start building tribal alliances; and then 500 Maori with 50 muskets begin attacking other Maori to the south. They especially want to wipe out the Whangarei, Coromandel and Auckland Maori. Their leader is Hongi Hika.

Together with Hokianga Harbour and Kawhia Harbour Maori, they raid along the west coast as far as Taranaki and Wellington; inland as far as Lake Taupo and Waikato; and along the east coast to Tauranga, Urewera and Gisborne (1818-1819).

They claim to have burned down 500 villages, taken 1,000 prisoners, and collected 70 human heads as trophies. They return home; produce more flax, wheat, pork and potatoes; and then trade for more muskets. For they’ll soon be off again.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Three

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Four