Yesterday Chris Trotter’s Insight: Politics article, ‘Why Aren’t Those People Being Arrested?’ looked at iwi checkpoints, the reaction to them by the public and the context of the actions of the iwi who set them up.

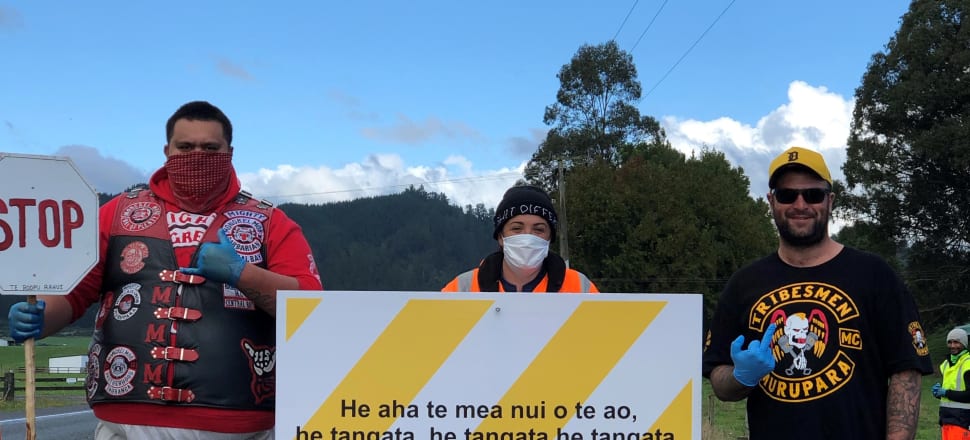

THE CLAMOUR for the Government and the Police to “do something” about Maori communities blocking roads grows ever louder. Many New Zealanders cannot understand why citizens without the requisite legal authority are being allowed to intercept and question their fellow citizens. Those same New Zealanders are asking (privately!) whether concerned Pakeha intercepting and questioning Maori travellers at checkpoints: “Where are you going, sir? What is the purpose of your travel?”; would be met with a similar level of official tolerance.

Chris reflected that had Pakeha acted in the same way, their actions would be condemned as “racist” as well as “provocative”. However, instead of concluding that there should be one law for all and that the iwi checkpoints should not have been allowed by the police, Chris made an argument that the “context” of the iwi’s action is why they needed to be treated differently to the rest of us by the Police and why the public should not be up in arms about their lawbreaking.

What lies behind this glaring discrepancy? What makes police officers, observing activities which are pretty certainly illegal, refrain from intervening?

Part of the answer lies in the historical fate of Maori during the last great global pandemic. Back in 1918-19, the deadly H1N1 influenza virus devastated many of the isolated rural communities in which most Maori New Zealanders then lived. Very little help was forthcoming from a Pakeha health system already stretched to breaking point. In many cases the only assistance available to the sick was from traditional healers. Unfortunately, their efforts not only failed to contain the virus, but, thanks to the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907, they were also deemed illegal.

What followed was an interesting history lesson but not one that led me to the same conclusion as Chris.

Chris saw the checkpoints as a largely symbolic exercise but I see them as being a vehicle for Maori activists who have a separatist agenda. They have seen an opportunity to take control and to advance their goal of Maori rule over areas where the majority of the population are Maori.

Of course, there would also have been fear driving the creation of the checkpoints but it would be naive to think that there was nothing more to it than that.

Even the Maori King seized the opportunity to start telling people what they can and can’t do by putting a Rahui on the Waikato River.

One of the reasons for allowing the illegal checkpoints that Chris put forward was the repercussions of shutting them down.

“If police had failed to understand the strength of that [local] feeling and tried to shut the checkpoints down, there could have been protests which would have required a larger police presence.”

That reason is one that I strongly disagree with as I have seen the consequences of that type of policing in the UK. There, I have seen again and again in YouTube videos, a group of people threaten to assault or kill an individual or a peaceful group who are exercising their right to freedom of speech or the freedom to take part in a peaceful march; but the police take the path of least resistance. They come down hard on the peaceful speaker or the peaceful group for being allegedly “provocative” towards the violent and threatening mob. They take law-abiding people into custody and take away their freedom of speech “for their own protection”.

We do not want our police to take the path of least resistance because that means mob rule and that means that the law is no longer being upheld and neither are our individual rights.

Chris made the argument that enforcing the law would have diverted valuable police resources during the emergency. However, shutting the groups down wasn’t the only option available to police for handling the situation.

All the police had to do was to make an announcement on TV and radio that the checkpoints were illegal and that no citizen should feel obligated to stop at them or to answer any questions put to them. In the same announcement, they could state that while they were choosing not to deal with the iwi groups at that point in time there would be legal consequences for the individuals involved when the emergency was over.

They could even state that they would be posting a police officer at every checkpoint to monitor the groups and to ensure that no member of the public was stopped or coerced.

Chris made the point that “persuasion is better than force” and with that I agree. By pulling the rug out from under the iwi checkpoints Police could have protected our rights without going head to head with the groups. They could have set up their checkpoints unmolested while Joe Public drove past them confident that the police had his back and that there was no obligation to stop.

Whether the checkpoints were set up with the best of intentions or whether they were a power grab by Maori activists makes no difference to the law. Whether or not there was a sad historical backstory should make no difference to the law.

The law is the law is the law. I don’t care about your sad back story. I have plenty of my own. All I care about is equality under the law. There is nothing racist about that.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.