Somehow, sometime and from somewhere, the Maori (who didn’t have their name yet), came to New Zealand. And stayed. If they came from the Cook Islands or the Society Islands, it was a voyage of over 2,000 miles by outrigger canoe and sails in all kinds of weather. A trip not made overnight.

Yet when James Cook was in New Zealand for the first time in 1769, he noticed that the Maori only navigated by the sun and the stars, and that given a cloudy sky they were lost. From this observation, he reasoned that if the Maori had any long distance nautical navigational skills at one time which allowed them to reach these isolated islands, then they had long since lost them, and hadn’t travelled anywhere except along the shorelines of New Zealand for quite some time. Generations.

The Maori as a people almost defy you to classify them. Their most common characteristic was that at one time they were exclusively a tribal society, not a collective or united one. The name “Maori” didn’t exist. It took somebody from outside to see them as a distinctive people native to New Zealand, and to give them a name.

The Maori belonged to some estimated 38-53 main tribes (average: 45 tribes). Their only loyalty was to their tribe. Or their sub-tribe. Or their tribe family group. Or their tribal alliance. Or whatever faction of whatever part of their tribe suited them at the time. The Maori were tribal. In one way or another. Today’s tribal enemy could be tomorrow’s tribal ally. And next week’s enemy again.

Tribes held a tribal territory of which the sub-tribes had their own district. Although there was fighting within a tribe, they would also unite against a common enemy – another tribe. War was fought for territory, personal power, prestige or revenge. But fight they did. War was a way of life for the Maori.

There were numerous classes of chiefs based on tribe, sub-tribe, and tribe family group. Estimates are that there was one “chief” of some status or another, for every “tribe” of some 20-82 people (average: one chief for every 51 people).

Maori population estimates for 1769, the time when Cook arrived, are 100,000-110,000 (average 105,000). This means that there could have been somewhere around 2,333 people per tribe, and a total of some 2,059 chiefs in New Zealand (average: 46 chiefs per tribe).

Maori population estimates for 1840, the time of the Treaty of Waitangi, are 70,000-115,000 (average 92,500). This means that there could have been somewhere around 2,055 people per tribe and a total of some 1,814 chiefs in New Zealand (average: 40 chiefs per tribe).

This is an important fact to remember: The Maori had a lot of chiefs.

The second most common characteristic of the Maori is that they are not common. They are contradictory and non-conforming. Difficult to figure out. A complicated people. There are those that do, and those that don’t. Those that will, and those that won’t. Those that can, and those that can’t. Those that shall, and those that shan’t. The Maori do not fit neatly into any kind of category except a complex one. This characteristic comes through time and again about them. They are a complicated people.

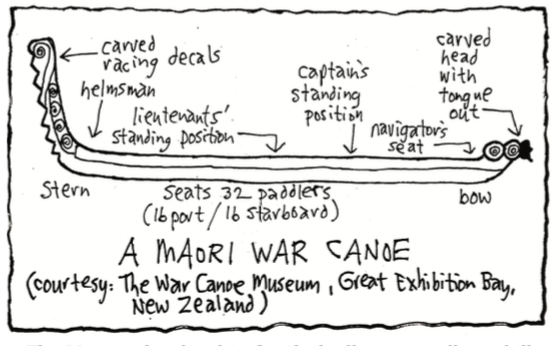

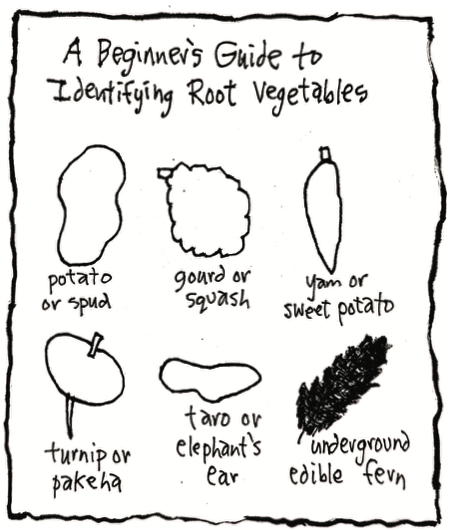

The Maori tribes lived in fortified villages, usually on hilltops (some 6,000 have been identified). They grew yams, taros, gourds and edible ferns; built 100 foot long canoes with sails made of flax matting that could hold 40 warriors; made things from bone, stone and wood both practical and ornamental; organised their life under a complicated system of beliefs and spirits; and had warfare as their favourite hobby.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ