On Saturday the Prime Minister sold us all a pipe dream. She said they were going hard and getting ahead of the virus, and that the goal was to “flatten the curve”.

Unfortunately, politics and the desire of the Prime Minister to be everyone’s friend, rather than a leader, means we’ve all been sold a lie.

Joscha Bach writes about this:

You have all seen a version of this curve of COVID-19 case loads by now:

What all these diagrams have in common:

1. They have no numbers on the axes. They don’t give you an idea how many cases it takes to overwhelm the medical system, and over how many days the epidemic will play out.

2. They suggest that currently, the medical system can deal with a large fraction (like maybe 2/3, 1/2 or 1/3) of the cases, but if we implement some mitigation measures, we can get the infections per day down to a level we can deal with.

3. They mean to tell you that we can get away without severe lockdowns as we are currently observing them in China and Italy. Instead, we let the infection burn through the entire population, until we have herd immunity (at 40% to 70%), and just space out the infections over a longer timespan.

You might recognise that chart. It happens to be the exact same chart that Jacinda Ardern clutched during her press conference.

The problem for the Prime Minister is that the curve is a lie:

These suggestions are dangerously wrong, and if implemented, will lead to incredible suffering and hardship. Let’s try to understand this by putting some numbers on the axes.

What is the capacity of the healthcare system?

This is a difficult question and cannot be answered in a short post like this. The US has about 924,100 hospital beds (2.8 per 1000 people). California has only 1.8. Countries like Germany have 8. South Korea has 12. (Their hospital system got overloaded nonetheless.) Most of these beds are in use, but we can create more, using improvisation (for instance using hotels and school gyms) and strategic resources of the military, national guard and other organizations.

We have the same as the US, around 2.8 beds per 1000 people. So our problems are as bad as what the US is facing.

Based on Chinese data, we can estimate that about 20% of COVID-19 cases are severe and require hospitalization. However, many severe cases will survive if they can be adequately provided for at home (which may include oxygen, IVs and isolation).

More important is the number of ICU beds, which by some estimates can be stretched to about a 100,000, and of which about 30,000 may be available. About 5% of all COVID-19 cases need intensive care, and without it, all of them will die. We can also increase the number of ICU beds somewhat, but the equipment that we need to deal with sepsis, kidney, liver and heart failure, severe pneumonia etc. cannot be stretched arbitrarily between them.

An important part of the equation are ventilators. Most of the critically ill COVID-19 cases die of an infection of the lungs that makes it impossible to breathe and even destroys so much tissue that the blood can no longer be sufficiently oxygenated. These patients need intubation and/or mechanical ventilation to give them a chance of survival, or even an ECMO machine, which oxygenates the blood directly. About 6% of all cases need a ventilator, and if hospitals put all existing ventilators to use, we have 160,000 of them. In addition, the CDC has a strategic stockpile of 8900 ventilators that can be deployed in hospitals that need them.

If we take the number of ventilators as a proximate limit on the medical resources, it means we can take care of up to 170,000 critically ill patients at the same time. (Not all patients in intensive care will need ventilation, and not all patients needing ventilation will be in intensive care, but there is a large overlap, and both groups will die without intervention.)

New Zealand had a ventilated ICU bed ratio of six ventilated beds per 100,000 people, and that was in 2005. I doubt we have any more. That is around 300 ventilated ICU beds.

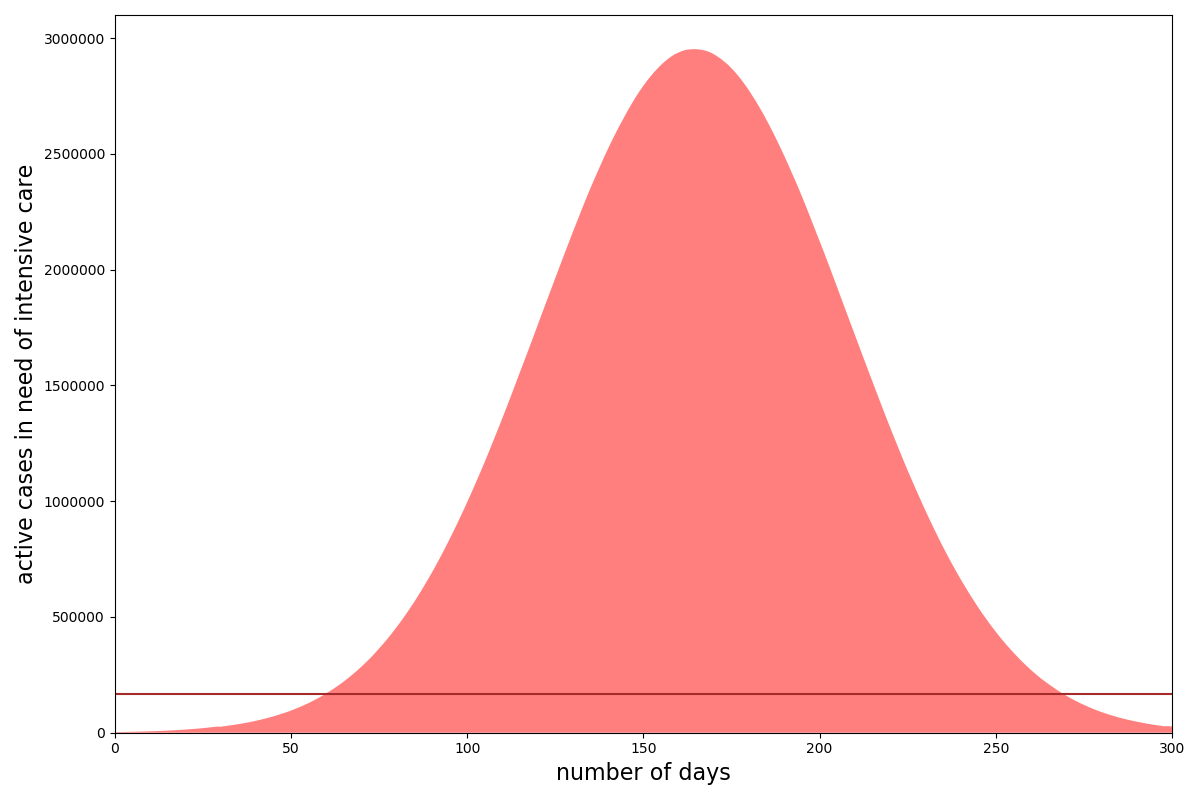

That all produces a chart like this:

That is the US, but we have a similar ratio, so the problem is the same.

The brown line near the bottom: that’s our limited supply of ventilators and intensive care beds! The red curve does not contain all cases of COVID-19, but only those 6% that will die if we cannot put them on a ventilator for something like four weeks. In this scenario, it means that the maximum number of cases needing care on the same day, without any kind of mitigation, is around 3 million! It’s clear that we need to desperately flatten this curve, because it means that for much of the year, the vast majority of cases will not even get assessed for intubation and critical care.

So will flattening the curve work like the Prime Minister says it will? Well, the short answer is no.

Dampening the infection rate of COVID-19 to a level that is compatible with our medical system means that we would have to spread the epidemic over more than a decade! … I am pretty confident that we will have found effective treatments until then, but you get the idea: reducing the infectivity of the new corona virus to a manageable level is simply not going to be possible by mitigation, it will require containment.

… The model is quite sensitive to the length of the stay in the ICU. If we get that down, fewer people will need these resources simultaneously, and the peaks of the curves will come down. We may be able to fight the inflammation during pneumonia, and reduce the number of critical cases. The available medical resources will increase over time to deal with the need. Regulations will be dropped, new treatments will be explored, and some of them will work. At some point in the near future, we may have to blow into a tube before we enter an airplane or an important public building, and a little screen tells us within seconds if our airways hold COVID-19, H1N1 or the common flu. But the point of my argument is not that we are doomed, or that 6% of our population has to die, but that we must understand that containment is unavoidable, and should not be postponed, because later containment is going to be less effective and more expensive, and leads to additional deaths.

The problem as I see it is that our government thinks that right now we are on the same timeline as Italy. We are not. We are lagging a month behind. They were at the same point we are at now a month ago. The government is hoping and praying that the cases will taper off this week. They are deluding themselves and putting Kiwis at risk. There are still three flights a day landing from China, a fact that even Simon Bridges was unaware of this morning when interviewed on radio.

Flattening the curve isn’t going to work unless drastic action is taken right now. We have to move to containment. That means looking at what South Korea has done, especially with schools. They shut them down.

China has demonstrated to us that containment works: the complete lockdown of Wuhan did not lead to starvation or riots, and it has allowed the country to prevent the spread of large number of cases into other regions. This made it possible to focus more medical resources on the region that needed it most (for instance, by sending more than 10000 extra doctors to Wuhan and the Hubei region). Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, now observes less than 10 cases per day. The rest of the Hubei region registered no new cases for over a week now. It is possible to stop the virus!

China has learned its lesson: after the lockdown of Hubei, other regions implemented effective containment measures as soon as the first cases emerged. The same happened in Singapore and Taiwan. South Korea was tracking its first 30 cases very well, until patient 31 infected over 1000 others on a church congregation.

For some reason, Western countries refused to learn the lesson. The virus spread in Italy, until their hospitals collapsed under the load. According to reports from the crisis region, resources became so scarce that older people or those with a history of cancer, organ transplants or diabetes were excluded from access to critical care. The US, UK and Germany are not yet at this point: they try to “flatten the curve” by implementing ineffective or half hearted measures that are only meant to slow down the spread of the disease, instead of containing it.

There will be some countries that do not have the necessary infrastructure to implement severe containment measures, which include widespread testing, quarantines, movement restrictions, travel restrictions, work restrictions, supply chain reorganization, school closures, childcare for people working in critical professions, production and distribution of protective equipment and medical supplies. This means that some countries will stomp out the virus and others will not. In a few months from now, the world will turn into red zones and green zones, and almost all travel from red zones into green zones will come to a halt, until an effective treatment for COVID-19 is found.

Flattening the curve is not an option for the United States, for the UK or Germany. Don’t tell your friends to flatten the curve. Let’s start containment and stop the curve.

David Farrar has suggested a Government of National Unity. I disagree, and the main reason I disagree is that sadly I don’t believe National would do any better. That is for two reasons, firstly that politicians look at the political fallout and act accordingly. If you think National under Simon Bridges would be doing anything different then you need to self-isolate and that is because of my second reason. The second reason is that the same officials would still be there advising that “flattening the curve” is the least disruptive politically. As you have read above, that is also the worst advice.

The government sat on the details of the sixth patient. That was for purely political reasons. They had been in the hospital for a week, so it is inconceivable that the government didn’t know. The details were withheld because the Prime Minister was still focussed on world news and photo opportunities for March 15. I believe the government planned Saturday’s announcement for Monday. What upset the apple cart was the dickhead from Australia and the Danish tart in Queenstown. That necessitated an urgent cabinet meeting on Saturday and where we are now.

You can’t put the poo back in the donkey, what is done is done. But what is needed now is leadership, not frowny, concerned faces. Things are going to get real, fast.

Containment is what is needed, now.