Professor Anne-Marie Brady

Supplementary Submission to the New Zealand Parliament Justice Select Committee Inquiry into Foreign Interference Activities, 2019

- Part One: Magic Weapons

- Part Two: Leninist tactic

- Part Three: Soft Power

- Part Four: Making NZ Serve China

4. One Belt, One Road

This is the Xi government’s initiative to create a China-centred economic bloc, one that is “beyond ideology” and will reshape the global order. One Belt, One Road, also known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), builds on, and greatly extends, the “going out” policy launched in 1999 in the Jiang era and continued into the Hu era, which encouraged public-private partnerships between Chinese SOEs and Chinese Red Capitalists in China and overseas to acquire global natural resource assets and seek international infrastructure projects.

Agencies:

National Development and Reform Commission (lead agency), State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and other relevant state agencies, Chinese SOEs and Red Capitalists, Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries or such CCP united front organizations.

Policies:

- Use OBOR to stimulate China’s economic development via external projects; secure access to strategic natural resources.

- Set up trade zones, ports, and communications infrastructure that connects back to China.

- Provide China-based “China-model” training programs and exchanges for foreign government officials.

- Get foreign governments to do the work of promoting China’s OBOR to their own citizens and neighboring states (another version of “borrowing a boat”).

- Work closely with both national and local government leaders on OBOR projects. Local governments control considerable assets and can make planning decisions at the local level.

- Invest in both China-based and foreign-based OBOR think tanks to help shape global public opinion, strengthen China’s soft power, improve China’s international visibility, and ability to help shape new global norms.

- Offer governments who sign up to OBOR privileged access to the Chinese market.

- Draw on the resources and assistance of overseas Chinese entrepreneurs to extend the objectives of OBOR.

- Promote the view that that OBOR is a win-win strategy both for China and the countries who accept OBOR projects.

- Use united front work to increase support for OBOR.

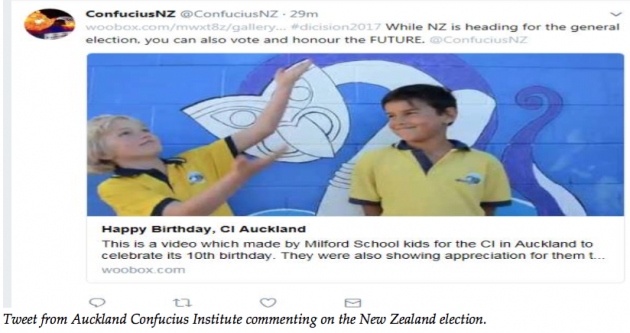

Tweet from Auckland Confucius Institute commenting on the New Zealand election.

Why New Zealand is of interest to China

Unlike Australia, New Zealand does not have many of the strategic mineral resources that China needs for its industrial development. But New Zealand is of interest to China for a number of significant reasons.

First of all, the New Zealand government is responsible for the defence and foreign affairs of three other territories in the South Pacific: the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau—which potentially means four votes for China at international organisations.

New Zealand is a claimant state in Antarctica and one of the closest access points there; China has a long-term strategic agenda in Antarctica that will require the cooperation of established Antarctic states such as New Zealand.

New Zealand has cheap arable land and a sparse population and China is seeking to access foreign arable land to improve its food safety. New Zealand now supplies 24 percent of China’s foreign milk, and China is the biggest foreign investor in New Zealand’s dairy sector.

New Zealand is useful for near-space research; which is an important new area of research for the PLA as it expands its long-range precision missiles, as well as having civilian applications. Chinese companies Shanghai Pengxin and KuangChi Science have used Shanghai Pengxin’s New Zealand dairy farms for near-space launches.

New Zealand also has unexplored oil and gas resources.

In 2016, New Zealand was described as being “at the heart” of global money laundering. The Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau are well-known as tax havens and money laundering nations.

New Zealand is also a member of the UKUSA intelligence agreement, the Five Power Defense Arrangement, and the unofficial ABCA grouping of militaries, as well as a NATO partner state. Breaking New Zealand out of these military groupings and away from its traditional partners, or at the very least, getting New Zealand to agree to stop spying on China for the Five Eyes, would be a major coup for China’s strategic goal of becoming a global great power.

New Zealand’s ever-closer economic, political, and military relationship with China, is seen by Beijing as an exemplar to Australia, the small island nations in the South Pacific, as well as more broadly, other Western states. New Zealand is valuable to China, as well to other states such as Russia, as a soft underbelly to access Five Eyes intelligence.

New Zealand is also a potential strategic site for the PLA-Navy’s Southern Hemisphere future naval facilities and a future Beidou-2 ground station—there are already several of these in Antarctica.

All of these aspects make New Zealand of interest to China’s Party-State-Military- Market nexus. Unlike the Cold War years when the CCP’s agents and spies were united by a common faith in Maoism-Marxism-Leninism, in the present day, modern-day agents of influence may be working to extend political and strategic interests at one moment, while lining their own pockets in the next. Current policy encourages the blurring of political and economic interests in the pursuit of extending China’s soft power.

China hasn’t had to pressure New Zealand to accept China’s soft power activities and political influence. The New Zealand government has actively courted it. Ever since New Zealand-PRC diplomatic relations were established in 1972, successive New Zealand governments have followed policies of attracting Beijing’s attention and favour through high profile support for China’s new economic agendas.

New Zealand has strived to always be the first Western country to sign up to China’s new external economic policies, whether it is China’s entry into the WTO, a Free Trade Agreement with China, the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), and most recently the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI/OBOR).

New Zealand governments have also encouraged China to be active in New Zealand’s region—from the South Pacific to Antarctica; initially as a balance to Soviet influence, as an aid donor and scientific partner, and lately, as part of “diversification” of New Zealand’s military links away from Five Eyes partnerships.7

As a small state which relies on international trade for economic prosperity and the protection of great powers for its security, New Zealand is very vulnerable to shifts in the global balance of economic and political power. New Zealand has had an extended transition from being a colony of the United Kingdom (UK) to full independence. Like most small states, New Zealand looks to larger powers for its security.

In the early 1970s the New Zealand economy was rocked by the UK’s entry into the Common Market and the global oil crisis. Formerly known as the UK’s “farm” in the South Pacific, New Zealand’s economic prosperity was founded on access to the British market, and until the fall of Singapore in 1942, New Zealand’s security was also protected by the UK. With the post-WWII decline of British power, New Zealand benefited from the Atlantic Alliance to become an ally of the USA, united by the UKUSA Agreement and (the now defunct) ANZUS Agreement.

Since the mid-1980s, successive New Zealand governments have looked to China as the solution to the loss of access to the UK market. New Zealand retains strong military relations with the UK and US and other traditional partners. However, these days forty-four percent of New Zealand’s trade is with the Asia-Pacific, and China is New Zealand’s second-largest overall trading partner and largest market for tourism and milk products—New Zealand’s top two economic sectors.

New Zealand signed a Comprehensive Cooperative Relationship Agreement with China in 2003 and a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement with China in 2014.80 New Zealand is now expanding relations with China beyond trade, too and also into military cooperation. In contrast, the Trump presidency has not ratified the TPPA, which New Zealand helped to set up, and successive US presidencies have refused to sign an FTA with New Zealand—many believe in punishment for New Zealand’s 1987 anti-nuclear legislation. In 2013, New Zealand’s Minister of Defence, Dr Jonathan Coleman, admitted that New Zealand was currently “walking this path between the US and China.”

To be continued…

To read the submission in full you can download it below.