Statistics New Zealand Thursday morning released its monthly residential rentals series. I don’t usually pay any attention to these data but since I’d been thinking about the very low level of real interest rates, I decided to take a quick look for once.

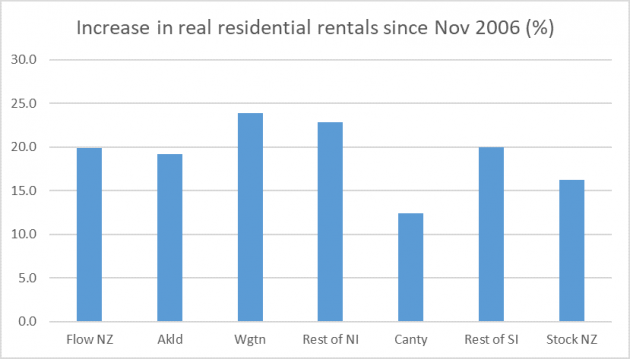

The series goes back to November 2006. They have both stock and flow-based measures, the latter being available on a regional basis. Nominal rents have risen by about 50 per cent since 2006, and these are the changes in real (CPI-adjusted) rentals on each of these measures over that period.

Something like a 15-20 per cent increase (depending on whether you prefer the stock or flow measure) over 13 years might not seem too bad. That’s a rate of increase of about 1 per cent per annum.

But that really is the wrong way to look at the issue. After all, renting a house/flat involves paying for the use of a long-lived asset. And the key influence that should influence any change in the supply price of such assets changes in the cost of finance, returns to alternative uses of money etc.

In November 2006 the real 10-year government bond rates was about 3.25 per cent (roughly so whether one uses the one indexed bond then on issue or takes a nominal bond yield and subtracts surveyed medium-term inflation expectations). The real 10-year bond rate is now about 0.15 per cent. What about the risk premium? The Treasury guidance to government agencies suggests using an equity risk premium of 7 per cent. One could play around with different estimates, and with assumptions about how much diversification housing might add to a portfolio. But it doesn’t seem unreasonable to work with a rough estimate that the required rate of return should have fallen by perhaps a third since 2006. All else equal, in a well-functioning market, we might reasonably have expected to have seen a significant fall in real rentals over that period.

Of course, the standard counter is “oh but falling interest rates raise the price of fixed assets”. Often enough that isn’t even true for assets in genuinely fixed supply – since long-term real interest rates rise and fall for reasons that often have something to do with the expected future returns in the wider economy – but even to the extent it is true, in a well-functioning housing market the only component of a “house plus land” bundle that is in genuinely fixed supply is unimproved land itself. The supply of anything else can be augmented, and in a well-functioning market almost without effective limit.

In a free market, in a country with as much land and as few people as New Zealand, most unimproved land isn’t very valuable at all. Just suppose it was worth $50000 a hectare (and actual New Zealand farmland traded at a median of just under $25000 a hectare most recently) and that you could get 7 houses to a hectare (a decent sized section and the associated roads and footpaths), the value of the unimproved land under a standalone house would be worth less than $10000. As something like a perpetuity, the lower interest rates might have raised that value by a third, an amount that – relative to New Zealand median residential prices – is really almost lost in the rounding.

The substantial reduction in real interest rates shouldn’t dramatically affect the supply price of a new building. Raw materials prices – timber, cement, fittings etc – should not be affected. Nor, really, should the price of labour: perhaps interest rates are low partly because productivity growth is low but, broadly speaking, any such weakness will be matched over time by lower growth in real wages. If anything, there is an in-principle argument that much lower interest rates may have lowered the supply price of new developments, because there is often quite a lag between acquiring land for development and being able to put the finished product on the market (inevitable market delays and regulatory delays), Lower interest rates mean lower costs of financing those lags.

In a well-functioning market it might not have been unreasonable to have expected, say, no change in nominal rents nationwide over the 13 years, not a 50 per cent increase.

But, of course, we don’t have a well-functioning market at all. We have one consistently and systematically rigged against competition and development by local councils and their central government enablers. There is no scarcity of unimproved land in New Zealand. But councils – councillors and staff planners – combine to create an artificial scarcity of developable land, such that in the face of one of the largest falls in real interest rates in history, to unprecedentedly low levels, rental housing is not abundant and cheap (as readily reproducible longlived assets should be in this climate) but scarce and expensive. Utter government failure if ever I saw one.

Bits of both arms of government occasionally talk a good game about freeing up land supply, but it is central government that is currently consulting on making less peripheral land available. It is a senior member of the Labour Party council – a Wellington city councillor – who when she rang me on a canvassing call a few weeks ago offered the unprompted observation (when I asked about fixing housing) that she didn’t want any more of that “sprawl” – this in a city with abundant, if often undulating, land. In many cases, their vision is to have us packed in like sardines – more “efficient” like that, supposedly – and they feed that personal preference, or sense of inevitability, by making land so expensive that many people feel they no longer have that historic New World option of space – in cities that, by global standards, remain pretty small.

When people complain about rents, and particularly the plight of people at the bottom with few choices but to rent, they need to sheet home responsibility to our governors – central and local. Perhaps a future National government would be different, but they too talked a good talk when they were last in Opposition and did nothing then. There isn’t yet much reason to think they’d be different next time.

Whatever the other risks, downsides, and complications of exceptionally low interest rates, the market has delivered a climate in which the real cost of decent housing should never have been cheaper. It takes governments – central and local, left and right ( in this area a distinction without a difference as they all enable planners) – to have produced rising real rents in a decade like this.