Chris Penk

First published by The BFD 25th June 2020

The BFD is serialising National MP Chris Penk’s book Flattening the Country by publishing an extract every day.

Stop the press!

One of the sectors thrown into considerable chaos by the government’s coronavirus choices is the media.

First, consider the difficulties that the Fourth Estate faced in trying to get answers from an administration determined to control the narrative to an extraordinary extent.

As Newshub’s Michael Morrah explained:

Early in this crisis, I put a simple question to the Health Ministry’s media team about Personal Protective Equipment. It took FOUR days to get a response, and when I did, the information provided was vague, unhelpful, and did not answer my question. […]

What’s happening now is that journalists are being referred to Dr Ashley Bloomfield’s daily 1pm press briefings in order to get the answers we need. […]

The room is filled with journalists from every media television, radio and print organisation in the country. Each of those journalists in the room have their own questions, plus questions from other colleagues in their organisation […].

The atmosphere is often tense, as journalists try to get their questions out before the officials call time, and it’s all over.

The daily briefings were tightly controlled affairs, with journalists invited by name to ask questions one-by-one. This is a situation rather different from the usual combative format that usually applies when politicians are questioned by the media in this country, where the Press Gallery are not expected to await invitations to participate.

I wonder how many of those listening to the press conferences were aware of the linguistic gymnastics that Ardern performs to avoid accountability.

To be fair, this is something that all politicians and the powerful do, at least to some extent. Those best at it are the most powerful.

But if it’s the job of a Prime Minister to move meaning then it’s the job of the rest of us to notice it. And to speak up.

Consider, for example, an exchange at one of the daily 1pm press briefings. The context was the fear of many Maori communities that various forms of inequality will be exacerbated by the emerging economic environment.

It’s a serious and important subject, obviously.

The journalist:

So your expectation is then, Prime Minister, that we look forward 3 months, 6 months, one year, two years that that gap will be less as opposed to going wider?

The Prime Minister:

Our goal as a government has always been to reduce inequalities; that is now our focus now more than ever.

Next question please.

While she’d moved on adroitly, it’s worth pausing to re-wind. The question had been what Ardern expected would happen in relation to inequality. Rather than answer with her expectation, she replied with intention.

For a politician with a poor record delivering on promises (think Kiwibuild, child poverty, light rail projects, homelessness, greenhouse gas emissions) the only safe space to occupy is one marked “intentions”.

It’s easy to indicate one’s good intentions. The road to hell is said to be paved with them.

Expectations are much more difficult to defend, as there’s a measure of accountability when they’re not met.

This government has fallen into the gap between rhetoric and reality so often in the past it’s little wonder that Ardern avoids concrete commitments wherever possible.

Perhaps she’s looked around the caucus room and noticed the calibre of her colleagues as deliverers of decent outcomes. And that her partners in coalition crime are that ultimate odd couple: New Zealand First and the Green Party.

Anyway, back to the question of how the media might be expected to survive in a financial situation that was growing tighter by the deadline.

These straitened circumstances were the context for a move criticised by some as highly convenient to government, whereby the public purse was to be opened to the tune of $50m, with contestable funding elements.

Whether by accident or design, the current Cabinet has instituted a system that’s underpinned by an obvious conflict of interest. Will Ministers look favourably upon applications for funding from media outlets or projects that have been staunch in holding them (yes, the Ministers themselves) to account?

Of course the justification was said to be that media companies were facing serious financial headwinds as a result of lower revenue throughout (and likely to persist beyond) the coronavirus crisis.

It made sense, in some ways, for the government to recognise and respond to difficulties now faced by the media, although many of these arising during the coronavirus crisis were fairly and squarely the result of government actions in the first instance.

Let’s look at the three key factors:

First, advertising revenue must surely have been hit hard by the strangulation of many Kiwi businesses to an extent that could only be described as “overkill” during the Level 4 lunacy.

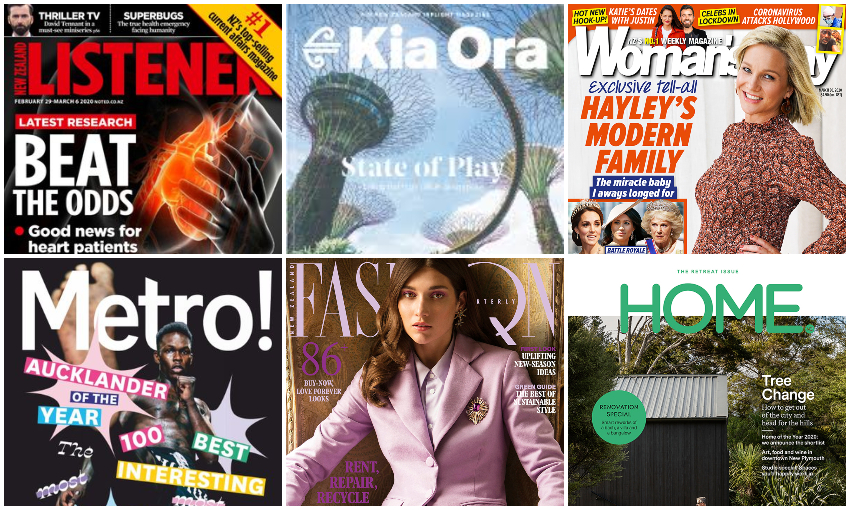

The case of magazine Bauer is instructive, as explained well in this Spinoff piece by Duncan Greive:

While the closure was a bombshell within the media, it was likely inevitable as soon as the decision around exclusion from essential services was made. With one small classification decision, New Zealand has lost a media powerhouse, home of much of our best investigative journalism, political analysis and cultural criticism. The very form of magazines is now perilously threatened – the printers, the shelf space in supermarkets, the many smaller operators, producing multi-award winning titles like New Zealand Doctor, Cuisine and New Zealand Geographic are still here, but remain essentially banned from operating.

The second factor was that large parts of the media were themselves denied the ability to operate. Magazines unable to be sold in supermarkets, the very same place that plenty of (other?) seemingly non-essential goods continued to be sold.

The community newspaper sector was thrown under a bus, presumably one unburdened by so-called non-essential workers.

Again, Duncan Greive at the Spinoff covered the situation with admirable clarity:

Publishers of magazines and community newspapers are reeling, after a ruling from their regulators at the Ministry of Culture and Heritage which has excluded non-daily print media from publishing through the level four lockdown. […]

Outside of community newspapers, the largest impact is on the magazine industry. […] Yet magazines are functionally no different to the likes of music radio or entertainment television, each of which are allowed to continue broadcasting. Additionally, with well over half their distribution happening through supermarkets, publishers are wondering why they aren’t being treated the same way as soft drinks or chocolate.

The third factor was that the government made little apparent effort to advertise in relatively humble homegrown outlets. The sentiments of the Christchurch Call (remember that?) were soon buried under an apparent avalanche of taxpayer-funded advertising on Facebook.

Social media companies became social pariahs when subjected to plenty of finger wagging 12 months ago. It turns out that finger wagging is compatible with shoulder shrugging, however, as the government had no qualms in funnelling cash into the multi-national Goliaths even as it denied domestic Davids a fair fight.